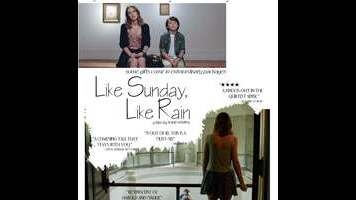

Reggie’s mother Barbara, overplayed by Debra Messing as a cartoon who falls short of monstrous only because she’s too exhausted for real cruelty, does indeed hire Eleanor as a live-in caretaker. Shortly thereafter, Barbara departs on an extended trip, leaving Reggie, Eleanor, and the movie alone. There are some mild intrusions of Eleanor-related melodrama in the form of her fractured upstate family and her dopey musician ex (whose single note is hammered by Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong). But for long stretches, not much happens—at least not by the standard of movies where a precocious child and semi-responsible adult teach each other things. The camera lingers on Reggie and Eleanor as they walk around Central Park, talk about themselves, and form a bond. They fail to develop the kind of initial, mutual antagonism so common to babysitter stories, and that failure is one of Sunday’s best qualities.

One of its worst, unfortunately, is Reggie himself. Because his cello-playing, music-composing, adult-book-reading melancholy apparently doesn’t qualify the character as unusual enough, the movie has Shatkin talk with an exaggerated formality. Like Fanning in Uptown Girls, he’s supposed to sound like an adorably miniature adult. But Reggie doesn’t sound at all like an adult; he sounds like a screenwriter carefully composing and phrasing his words to make exposition sound sophisticated: “I have a great deal of understanding, well beyond my years,” the kid announces. Later he says, “I think about things; it’s my nature,” the kind of self-analysis that talks down to the invisible movie audience. It’s possible that writer-director Frank Whaley intends for Reggie to sound this calculated, but the movie doesn’t play it that way. It’s treated as a charming quirk that takes but a moment of adjustment for Eleanor. She takes to Reggie’s peculiarities almost immediately.

Meester, to her credit, sells that affection with natural warmth; in a nicely subtle touch, Eleanor even begins to adopt a few of Reggie’s formalized speaking tics as their relationship grows closer. Meester’s empathetic performance almost makes Shatkin’s relentless lack of childlike qualities work for the movie, normalizing a blatant conceit and turning them into unlikely friends. The lack of dramatic tension between the two is touching, and gives way to an intriguing ambiguity over whether Reggie sees Eleanor as a surrogate mother, a cool older sister, a peer, or an inappropriate crush. So much of Like Sunday, Like Rain is suffused with such lovely, understated melancholy that it’s a shame when it nudges too hard, as with Reggie’s smarmiest dialogue or the deployment of its gently maddening piano-heavy score. Whaley aims high for this sort of material, but his film, sweet as it is, gets a little too precocious.