Knight is best known for a world that he only partially created. In 1955, he helped his friend Kay Thompson with a picture book, Eloise: A Book For Precocious Grown-Ups, about a mischievous, playful little girl (a lot like Thompson) who had the run of New York’s Plaza Hotel (again, a lot like Thompson). Eloise was so successful that it spawned three sequels, and Thompson and Knight were well into a fourth when they had a falling out, after which Knight found himself out of the Eloise business for several decades. After Thompson died in 1998, the property was revived, resulting in the 2002 publication of a long-shelved fifth book, Eloise Takes A Bawth.

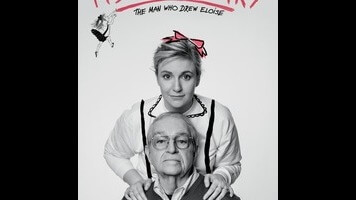

It’s Me, Hilary tells the tangled story of Knight’s involvement with one of the most beloved kid-lit characters of the mid-20th-century. The story doesn’t entirely end happily, because once major media companies started seeing new profit potential in the Plaza’s top tyke, Knight began to feel squeezed out again. The film also touches on some of Knight’s other books and commercial work, and covers a couple of key points from his personal life (such as his homosexuality, and the influence of his parents, who were both successful artists working in very different genres). A lot of It’s Me, Hilary is concerned with how Knight spends his time in his old age, conceiving and shooting little movies around his property. His philosophy has always been that “play is how you prepare for work.” Besides, he says, “I’m excellent at fucking off.”

Dunham, her co-producer Jenni Konner, and director Matt Wolf (the latter of whom also made the very fine documentaries Teenage and Wild Combination: A Portrait Of Arthur Russell) try to fit a lot into 35 minutes. Testimonial interviews with the likes of Fran Lebowitz, Mindy Kaling, and Tavi Gevinson come and go too quickly, especially given that all three of them make sharp points about the appeal of Eloise—Gevinson calling the series “a feminist primer” and Lebowitz saying that “the Plaza” represents the inherent glamour of adulthood. Since Knight even laments at one point that he’s really only known for Eloise when he accomplished so much more, the large proportion of It’s Me, Hilary devoted to Thompson’s books seems unfair.

Then again, they are great books, lively and so beautifully drawn. And Thompson is such a character that she deserves her own HBO documentary, of equal or double length, all about her days singing on the radio in the ’30s, working as a vocal arranger for MGM in the ’40s, playing a fashion magazine maven in the 1957 musical Funny Face. In a vintage interview, Jerry Lewis raves over Thompson’s nightclub show, saying, “She’s more than an act; she’s an experience.” And in the clips of Thompson here, talking about Eloise on television, she’s a real dynamo, coming across like a lanky middle-aged version of her most famous creation.

According to Knight, she could be both childlike and childish. He says that when she started destroying his original artwork and interfering with him while he was trying to draw, he decided to end their partnership. Knight’s memories of what drove him away from Eloise speak to that need for control that Dunham mentions, but they also say a lot about Thompson, an outsize personality who seems to have bristled at someone else getting praised for the books she wrote. It’s Me, Hilary could’ve easily have generated another half-hour or more of material out of the complicated relationship between the actress and the artist.

Regardless, for those who pine for that particular mid-century heyday of New York City society—an era when early TV panel shows would gather Broadway stars, radio personalities, and bestselling authors, and would assume that home viewers knew who they all were—It’s Me, Hilary becomes a warm evocation of a time gone by, similar to Knight’s old drawings of the Plaza. That sense of a lost wonderland is reflected in Dunham’s eyes when she walks into Knight’s apartment and looks around, clearly delighted to be a part of his “curated world.” Who wouldn’t be?