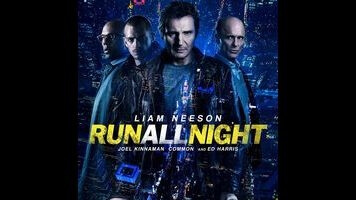

Liam Neeson rips up New York City in Run All Night

Director Jaume Collet-Serra’s third consecutive Liam Neeson movie, Run All Night, feels like a letdown after the Euro-thriller twists of Unknown and the locked-room crisscrossing of Non-Stop. Working again with a ticking-clock premise—which finds hit man Jimmy (Neeson) ripping through New York in order to keep his Irish mob buddies from killing his estranged son Mike (Joel Kinnaman)—Collet-Serra can’t seem to organize the same sense of urgency, even as he zips through boroughs and buildings in elaborate Panic Room-style digital composites. But even though he never gets a grip on the over-complicated plot, the director hasn’t lost his knack for those elemental qualities that make a good action flick. This is a movie of men facing off in rail yards minutes before dawn, scaling geometrically perfect housing project balconies, and giving chase through rows of backyards, leaping every wire fence as though it were an Olympic hurdle—deadly endurance tests staged in nocturnal, decrepit urban space.

At the bottom of it all is an archetypal battle of wills, between Jimmy and big boss Shawn (Ed Harris), the first honest-to-God antagonist to grace one of Neeson’s violent thrillers. Jimmy is basically Liam Neeson Bingo, an alcoholic widower haunted by guilt, once feared, but now a harmless joke who dresses up as Santa for the other mobsters’ kids in exchange for booze and pocket money. Shawn is his protector, the millionaire kingpin who fixes Jimmy hangover meals; corny as it may sound, he seems to genuinely love the guy. And when a convoluted series of events—involving Shawn’s idiot son and a heroin deal gone bad—sets them against each other, they seem less angry than hurt.

If Run All Night were a contest to prove which actor can take a pulp script more seriously, then Neeson and Harris would be in a dead heat. Since Neeson’s post-Taken reinvention as a Charles Bronson-esque action star, it’s become common for critics to refer to his commanding presence as though it were classing up material that would otherwise be below him. But the truth is that, at this point, Neeson mostly stars in movie that seem written (or at least significantly re-written) for him; the projects he chooses are so consistent in theme that he has as much of a claim to authorship as anyone else.

Run All Night—fixated on grief, regret, alcoholism, and impending death—is no exception. “We cross that line together” is a line Jimmy and Shawn echo back to each other throughout the movie. It’s supposed to symbolize a mindset and a bond, but, perhaps inadvertently, it also connects the movie’s attitude toward death with Collet-Serra’s preoccupation with city grids and architectural geometries. As far as Run All Night is concerned, action is all about crossing lines: cars smashing through lanes of traffic, figures weaving through subway cars, walls getting slammed through, friends and family killing each other. The movie piles on crooked cops, good cops, neighborhood kids, high-tech contract killers, and even Albanian gangsters, a Neeson classic. Underneath all those squiggles of plot and subplot, however, is something simpler and more fundamental.