What does it say that most movies about making contact with an alien species inevitably devolve into a bloodbath? Is that mankind’s fear of the great unknown rearing its ugly head? Or, Arrival aside, is it just more fun (and profitable) when E.T. goes HAM? In the ruthless science-fiction thriller Life, a team of researchers aboard the International Space Station acquire definitive proof that we’re not alone in the universe: a carbon-based organism from Mars, small enough to fit into a petri dish. Unfortunately, and much to their surprise (though not to the audience’s), the little guy turns out to be something of a natural born killer. Life plays coy about this development for a while, going heavy on the oohs and the aahs and the proud video chats back to Earth; when the title arrives, more than a few minutes in, it’s to a swell of hopeful music. But astute viewers will see the truth in the opening shot, with its familiar, unbroken stare into the inky black void of space. The void stares back, menacingly.

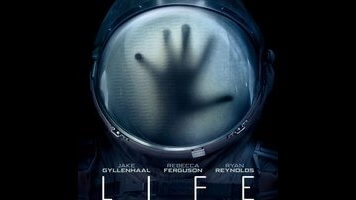

Life is a B movie on an A budget, an old-fashioned creature feature that delivers its cheap thrills expensively. From a visual and technological standpoint, one could call it post-Gravity: Most of the film is set within a high-tech orbiting spacecraft, and director Daniel Espinosa (Safe House, Child 44) takes the weightlessness of the environment as inspiration, his camera floating constantly around the characters and down long passageways, pivoting upside down, catching majestic glimpses of the cosmos in the corner of the frame. Conceptually, however, it’s of an older breed. Like, 1979 old. Think of a vicious shape, blurring across the foreground and blipping across a radar screen. Think, too, of airlocks in the third act, and of tentacles wrapping tightly around bodies. “How smart is this thing?” asks Rebecca Ferguson’s pragmatic microbiologist. If she has to ask, she’s not going to like the answer.

Once the pretense of awe and wonder is dropped, Life gets down to business, sending crew members scrambling across the station, closing hatches, trying (in Martian parlance) to science the shit out of their dilemma. “Calvin,” as some grade-schoolers back home name the hostile bastard, grows rapidly into a murderous space octopus, slipping through tight spaces, crunching bones in its clammy embrace, and swimming in the low gravity like a hungry shark in open water. The beast is more interesting, certainly, than his prey: the carelessly curious and paraplegic scientist (Ariyon Bakare); the haunted war veteran (Jake Gyllenhaal); the proud new father (Hiroyuki Sanada, back in a space suit a decade after Sunshine). Hired mostly to bob and weave through a meticulous recreation of ISS, the overqualified cast nonetheless takes this hokum dead seriously—though Ryan Reynolds, reunited with the screenwriters of his Deadpool, gets to break the tension with a few wisecracks.

For as much as it gussies up its primal scenario with lots of NASA verisimilitude and techno babble, Life doesn’t have much more on its lizard brain than another deep-space round of And Then There Were None. But the film has a nasty edge, a visceral mean streak, that’s genuinely bracing. The ending, for one, plays cruelly on the optimistic imagery of another recent space thriller (and on one of the choice soundtrack cuts of a recent space opera). And then there’s the earlier scene where the monster manages to thrust itself down one of these poor astronauts’ gullets, making short and squishy work of what’s inside. We don’t see much, but we don’t need to, because lord, the sounds. In space, no one can hear you scream. In space movies, every dying gurgle comes through loud and clear.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.