Like its cursed hero, Stephen King’s Elevation is bizarrely thin

As Halloween approaches in the peculiar Maine hamlet of Castle Rock, a graphic designer named Scott Carey steps out of the shower and onto a bathroom scale. He then overdresses, picks up a pair of 20-pound weights, and steps on again. The scale reads the same amount. When he tries it again the next day, he weighs less. Now, isn’t that strange.

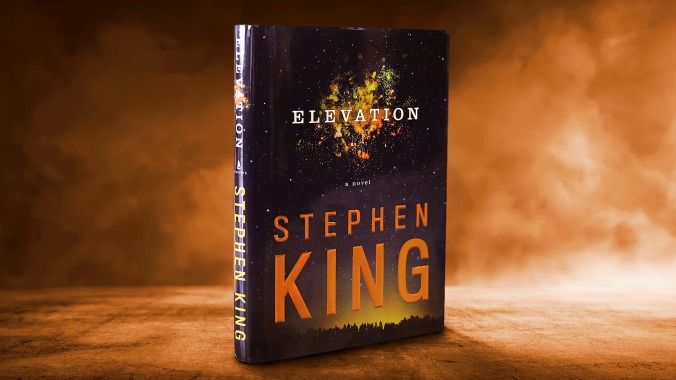

So begins Elevation, the latest work by Stephen King, and an unexpected one. Who would’ve guessed that King would have new notes to strike nearly 45 years after emerging onto the scene, but he strikes them here, in a piece that’s thoughtful and even moving at times, without ever being particularly satisfying.

Elevation comes billed as a novel, but it’s really a novella, just shy of 150 pages. It would fit unobtrusively into a collection of longer short fiction like Different Seasons or Four Past Midnight, and compared with those, it can’t help but feel like a bit of a rip-off existing on its own. Reading it is like going to a great restaurant and only getting one course of a tasting menu.

The book’s premise, of something bizarre happening to a man’s weight, most obviously recalls King’s Thinner, published under his Richard Bachman pseudonym. That one was about a man who can’t stop losing weight after he’s been cursed, his body irreparably wasting away. Elevation has a man getting lighter, but invisibly so. His obese body stays the same, but as time passes, gravity acts less upon it, until eventually he may as well be bounding around the surface of the moon.

The story, to the extent there is one, isn’t about uncovering the source of Scott’s affliction, nor is it about his trying to halt or even slow the progress. One can’t even say it’s about his grappling with the implications of what’s happening to him, since the weight loss starts by making him feel great, after which he’s soon propelled to the acceptance stage of the grief cycle. Considering how little happens, too much of the book is dedicated to a half-marathon where Scott uses his lightness to his advantage. (Perhaps viewers of Castle Rock will find this a more rewarding read, as it continues King’s career-long love of Easter eggs, including a local band named after Pennywise.)

Inevitably, all this means that Elevation wants for conventional drama, even if there’s something touching in the idea of a malevolent force being greeted with gratitude rather than fear. It’s somewhat reminiscent of Four Past Midnight’s The Langoliers, but that one had mystery, tension, and drama, and would have more comfortably existed as a satisfying stand-alone.

Elevation comes a scant five months after The Outsider, a crackling yarn about a shape-shifting monster that I called “an It for the Trump era,” which King himself disputed. So is it churlish to think he’s returned to the political well? Even if you set aside some pointed throwaway lines (“The politically progressive minority spoke of global warming; the more conservative majority called it an especially fine Indian summer that would soon be followed by a typical Maine winter; everyone enjoyed it”), Castle Rock’s conservative politics—“the country went for Trump three-to-one”—play a prominent role in the proceedings. The biggest arc in the book doesn’t involve Scott or his gut, but his neighbors, a lesbian couple who first responds to the town’s prejudice against them with hostility, only to be “elevated” themselves, both in their local reputation and the way they view the town in return.

This is a lovely idea, a supernatural force swooping in to help heal our national rifts, but it’s easy to imagine King exploring this in a more complex or challenging way. If nothing else, you want a story to go along with the idea, or at least more ideas for your money. This one is for completists only, and devoted ones at that.