Lion doesn’t quite make its true story roar

Like its hero, Lion often finds itself torn between two worlds. Garth Davis’ film is working from true source material: Saroo Brierley was separated from his family as a child in India and adopted by an Australian couple; years later, he discovered his birthplace using Google Earth. But in trying to tell the whole of this nearly implausible tale, the film can’t figure out whether it’s more invested in young Saroo’s harrowing journey or older Saroo’s feeling of displacement.

Instead of adopting a present-day framing device, Lion initially unfolds chronologically, beginning with Saroo (Sunny Pawar) as a boy helping his mother and brother in Khandwa. One evening he—adorably, it should be noted—demands that his brother, Guddu (Abhishek Bharate), take him along on a trip to find work. When Saroo’s too sleepy to participate, Guddu leaves him on a bench. Saroo wakes up abandoned, boards a train to look for his sibling, and finds himself trapped as it starts to move. He’s dropped miles away in Calcutta, where he is not only alone, but also unable to speak to anyone. The crowds chatter in Bengali; he only uses Hindi.

Davis deftly conveys the desolation of Saroo’s situation without wallowing in it, and Pawar gives a terrific performance. The first-time actor is able to transform from a happy, rambunctious adventurer into a dejected soul, both mystified and terrified by the world around him. Saroo is a chatty kid around his family, but when he loses the ability to communicate, he grows introverted. His identity has been ripped away from him, just as his home has. Davis, throughout this part of the film, plays with the idea of smallness. The opening finds the camera panning over a series of landscapes, finally revealing a tiny figure running. It’s a nod to the technology that will be a factor later in the movie, but also to the vastness of the world around Saroo.

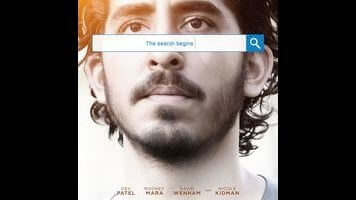

But that’s only half the movie. When we meet grown-up Saroo, he’s portrayed by Dev Patel and headed off to a hotel management course in Melbourne. There, a piece of food triggers the memory of his childhood and he becomes obsessed with finding his lost family. This causes friction in his relationships with his adoptive mother (Nicole Kidman), his troubled adoptive brother (Divian Ladwa), and his girlfriend (Rooney Mara). But given that the movie spends so much time with young Saroo, those relationships are not allowed to flourish. Almost as soon as the audience meets the adult version of the man, he is preoccupied with his past, which means we don’t get a sense of who he has become outside of that; the hints of Saroo as a charming, flirtatious twentysomething are frustratingly fleeting, and his pivot into torment comes too quickly for Patel to fully realize his character. (To convey just how invested Saroo is in his search, Davis relies on flashbacks/visions of his protagonist’s past.)

Meanwhile, Kidman gets a big, hokey speech, heavy on tears, that would be more affecting if we had a greater understanding of her sorrow. As for Mara, she’s mostly wasted in a boring supportive-girlfriend part. By splitting up the story into different eras of the hero’s life, Davis seems to be striving to avoid some of the conventions of melodrama. But coloring within the lines might have done a couple of favors to his actors and the flow of his film.

Davis also never overcomes the issue of the methodology Saroo uses to hunt for his birthplace. The concept of Google Earth is introduced by a minor character in clunky fashion, and Saroo spends vast amounts of time simply staring at a computer. When he’s not doing that, he’s making like Carrie Mathison in Homeland, and pinning thumbtacks to his wall. When the final revelation comes, it arrives as a sort of deus ex Google, and therefore feels unearned, despite its improbability. The ending, of course, is no surprise: Lion does eventually arrive at an emotional reunion. It just causes too much whiplash en route.