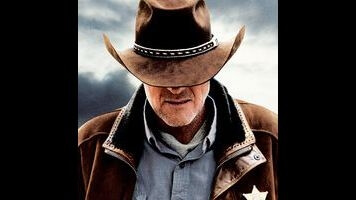

Longmire: “A Damn Shame”

Over the course of its first two episodes, Longmire’s greatest strength was also its greatest weakness.

This is a laconic show, sparse in its dialogue and storytelling, which I’d consider a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it means we get more time to sit back and watch characters working, allowing us to focus on the strong performances, nuanced character actions, and evocative location shooting on display in the series. However, on the other hand, the sparseness also means there’s less for us to latch onto: While I enjoyed the first two episodes, I also didn’t find them particularly memorable, and the lack of obvious accumulation can make it more difficult to get attached to the show. In other words, the same small charms that make Longmire a show worth recommending are also likely to make it more difficult for viewers to connect with the show.

“A Damn Shame” does little to change the show’s trajectory, although it’s helped me conceptualize the show’s approach to these early episodes. The show is engaged in what I’d call a “ride-along procedural” strategy, in which the viewer is like a rookie sitting in on two seasoned cops on their daily route. While crimes will be dealt with over the course of the ride-along, the rookie isn’t really there to help solve the crimes: The rookie is there to observe the other cops to get a sense of what this job entails, and what he or she might come to expect in the future.

Through three episodes, Longmire is still waiting for that procedural case that registers as something other a ride-along, more than a series of machinations through which to better learn about our main characters. The story of Ray Stewart’s suicide became the story of a former mobster who faked his own death—and murdered a stable full of horses—to protect his family, but the twist just felt like an easy way to create some gunfire and fisticuffs to bring the episode to its climax (since, at least based on previews, A&E really wants this to be perceived as an action-packed show, which it is not). Every move in the storyline was either initiated by one of our characters—like Ferg proving incompetent enough to give a fake U.S. Marshal the information necessary to take Ray’s family hostage—or initiated for one of our characters. Much as Longmire’s insistence on informing the victims’ families personally in the first two episodes reflected on his decency, his commitment to the injured horse from the barn offers a poignant ending that highlights his compassion (and draws a clear parallel between the injured horse and the injured Walt, whose secret Native American surgery/recovery served as our introduction to the episode).

This sort of character-driven storytelling is prominent in almost all procedurals, and I’d still—three episodes in—consider Longmire to be a fairly solid deployment of the formula. The challenge is that this creates a constant balancing act between subtle nods to the show’s setting and far more obvious nods to its broader themes. The idea that police work is different in this neck of the woods is often communicated through small details like Vic simply rolling the burnt cell phone up in her rubber glove instead of grabbing an evidence bag, or the laid back and often wryly funny atmosphere at the Sheriff’s office. In other moments, though, the arrival of the East Coast mob becomes an invasive comparison point, with Vic dropping an anvil-like “Back East, we’d have a SWAT team” to further underline that this isn’t the kind of situation Walt normally has to deal with.

In fact, this is the third episode in a row where the threat comes from “outside” of the community, with the Native Americans, the Mennonites, and now the Mafia all being represented as the “Other” whose different values or ethics threaten the moral code of the series. When Alice refuses to go along with Walt because she believes he could be in league with the mob, we know that he would never be involved with the mob because he isn’t that kind of cop. That we know this suggests that the show has done a good job of sketching out the character’s moral compass, but I do wonder if the lines of that sketch could have been a bit more gently drawn. Robert Taylor does a fabulous job of subtly revealing bits and pieces of Walt’s personality, but the script is still set on giving him emotional poem recitations delivered to injured horses set to “Hallelujah,” which is typical of ride-along procedurals but also something that ride-along procedurals need to lean away from with time.

Last year, I was watching “Cross Jurisdictions,” the CSI episode that served as the back-door pilot for CSI: Miami, and I was reminded how much that episode was built around introducing us to Horatio Caine. It wasn’t about who did the crime, but rather about putting David Caruso’s character in a position to offer security and comfort to a child in trouble, and to do everything in his power to bring the guilty party to justice. There, the need to introduce these new characters (and convince both the audience and executives they were worth following) took precedence over telling a procedural storyline, creating a contrived but effective vehicle through which to build a franchise.

Walt Longmire reminds me a bit of Horatio Caine, or at least the idea of Horatio Caine as outlined in that initial episode and undone by 10 seasons of terrible one-liners. He’s a man who cares about the values of his job more than the procedure, whose compassion is undeniable and yet occasionally indiscernible beneath a tough exterior. Taylor’s subtle performance outclasses Caruso's, but I can imagine that my parents’ longtime neighbors—who fit comfortably into the demographic for this show—would take to Walt for many of the same reasons they took to Horatio.

However, as much as Walt’s character is a huge part of the show’s early success, Longmire will be a better show when the narrative no longer feels like it exists purely to fuel Walt’s characterization. I’m not expecting Longmire to break free from its “procedural shackles,” both because I don’t consider procedural storylines to be inherently limiting and because we’re only three episodes into the series’ run. That being said, “A Damn Shame” relies on such patience too heavily, spending too much time telling us things that it could be showing us. As effective as it might be to use procedural storylines to reveal character details, there’s a fine line between clever intersection and writerly symbolism, and it’s a line the show has crossed in more than a few instances. It’s an understandable decision, but it runs contradictory to the more subtle work being done as part of the production, stagnating its growth when it should be fostering it.

As the rookie riding along in the backseat, I’m not yet seeing any major cause for concern, and I still have every intention of committing myself. However, I’m also still waiting for that moment where this can stop feeling like a ride-along, and we can finally get down to some real police work that gives us more insight into the show Longmire is rather than the show Longmire wants us to think it is. We’re here, and we’re watching: Now show us what you really brought us here for.

Stray observations:

- I’ve been wondering what purpose “The Ferg” served in the office since the pilot, so I was pleased to see a bit of a spotlight, even if his incompetence was a bit too well-choreographed for my tastes.

- Speaking of which, the foregrounding of the gravestone in an early shot at the Stewart farm made the “faked his death” angle way too obvious for that to be considered something close to a cliffhanger. Instead of making me feel smart for figuring it out, it makes me feel like the narrative is being dumbed down, and that does little to help the show combat its procedural pedigree (or lack thereof).

- While the New Mexico setting—or, rather, the Wyoming setting being played by New Mexico—is visually evocative, with the snow during tonight’s showdown offering a powerful and yet natural way of emphasizing its impact on the characters and the storytelling, I do wish we could get a better sense of the local culture/community. The few characters we’ve met have offered fairly broad representations of rural types and Native Americans. While time will help, as characters can recur and representations can be diversified, it’s definitely something the show should—to my mind—actively confront as the season progresses.

- While I would, of course, prefer bad CGI on a flaming horse to actually setting a horse on fire, I will say that the presence of any CGI on a show this down-to-earth seems strange. I feel the same way about the green screen during driving scenes on Justified.

- It appears that the election will, at least to this point, be confined to a few lines of dialogue each week—an interesting strategy, which we can judge more readily when the season inevitably ends with the election.

- Zack will be back next week for an episode that appears to up the guest star quota considerably—thanks for having me!