Introducing Endless Mode: A New Games & Anime Site from Paste

Here’s what’s so awesome about Looper: It’s a futuristic time-travel movie in which more or less the entire last hour takes place on a farm. And that’s just one of the many ways writer-director Rian Johnson subverts expectations. This is a “you know what would be cool?” movie that considers the real-world ramifications of its science-fiction whiz-bang, and a film of ideas that doesn’t skimp on the action. Most of all, Looper asks questions about whether a man’s destiny is locked into place—not because the future has already been written, but because of the kind of person he is.

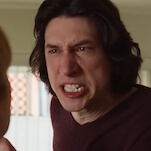

Joseph Gordon-Levitt stars as a lifelong ne’er-do-well who takes a job as a specialized kind of assassin, who kills and disposes of people sent back through time by the gangsters of the future. As Gordon-Levitt explains up top in voiceover, once time-travel has been discovered—a few decades after 2044, when Looper is mostly set—it’s immediately outlawed, and becomes the province of a demimonde that uses the technology to cover up its crimes. Gordon-Levitt was recruited into this “looper” job as a kid, which is almost like winning the lottery in the world of 2044. Loopers dress snappy, drive souped-up jet-propulsion vehicles, carry booming old-timey rifles, and get paid in silver bars, all of which places them among the upper-middle-class of the mid-21st century.

Problems ensue once Gordon-Levitt and the other loopers start recognizing that they’re increasingly each being asked to kill older versions of themselves, which “closes the loop” and ends their contracts, complete with a big payday and a retirement party. Some are wary of the implications of this, wondering what’ll happen to them in the decades to come, though most are too busy spending their bonus money to dwell on it for long. Then Gordon-Levitt’s older self—played by Bruce Willis—comes back, escapes, and announces that he’s going to fix everything, via extraordinary measures that Gordon-Levitt is determined to stop.

Viewers may bicker afterward about whether the time-travel in Looper makes sense—a criticism Johnson attempts to defuse via Willis’ comment that the whole process is “cloudy”—but undoubtedly the world of Looper has been carefully planned. Johnson doesn’t just throw cultural, societal, or fashion trends into the movie for weirdness’ sake; he makes the characters’ retro clothing central to the movie’s “everything recurs” theme, and he works the existence of telekinesis and roving vagrant mobs subtly into the background of the action, so he can foreground them as needed.

That level of care extends to the supporting roles and performances, which do more than just take up the spaces around Gordon-Levitt and Willis. Johnson makes good use of the usually bothersome Paul Dano, who puts his shriller attributes into play as a flashy looper whose problems plague Gordon-Levitt. Piper Perabo and Garret Dillahunt each get a couple of showcase scenes, as a showgirl and an enforcer, respectively. Jeff Daniels is hilariously world-weary and rumpled as a mob boss from the future who’s back in 2044 reluctantly monitoring the looper program. (Daniels has Looper’s best lines, which is saying something, because as Johnson showed with his Brick and The Brothers Bloom, he has a good ear for dialogue.)

But the heart of the movie belongs to Emily Blunt, as an iron-willed farmer looking after her whip-smart son (Pierce Gagnon, who gives one of the most assured performances by a child in movies this year, running a close second to Quvenzhané Wallis in Beasts Of The Southern Wild). After Willis escapes Gordon-Levitt, the latter determines that Willis will head to Blunt’s farm eventually, so he camps out there, and gets involved in the life of this steely woman and her strange little boy. Just when it seems like Looper is gearing up for a mind-blowing adventure in the distant future, it settles into more down-to-earth shootouts and chases in city streets and country roads, all haunted by the prospect of what the audience has been told will become of these shooters and chasers.

Outside of one jarring timeline hiccup, Looper’s how-the-present-affects-the-future shenanigans don’t jumble the narrative significantly. (Though there is one cool visual sequence that takes a few seconds to process, as a looper from the future watches his body fall apart while his past self is getting vivisected.) That’s because Looper isn’t playing clever time-games for their own sake, but rather considering their impact on the characters. Johnson’s main visual motif is cloudiness, suggesting how moments curl around each other, forming patterns. A lot of the people in Looper are dealing with similar issues—addiction, dead parents, life-changing love affairs—and the movie subtly explores the ways their mistakes recur, from life to life and time to time.

Comparisons to 12 Monkeys are inevitable, given Willis’ presence, though really, Looper is reminiscent of The Matrix—not so much in terms of its style or plot, but in that it’s so fully realized, and populated with memorable scenes and delightful character turns. And like The Matrix, Looper has a strong emotional core, as its two protagonists—young and old—embody the cycle of selfishness they see all around them, and show the potential for one person to break it. The odd logical inconsistency aside, Looper is a remarkable feat of imagination and execution, entertaining from start to finish, even as it asks the audience to contemplate how and why humanity keeps making the same rotten mistakes.