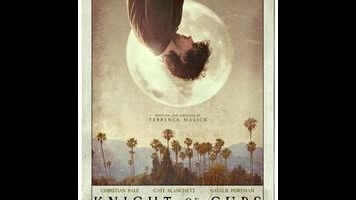

That’s really just another way of saying that Malick has provided, with his gorgeous meander of a seventh feature, plenty of ammunition for the faithful and the not. If his last film, To The Wonder, felt a bit like the B-side leftovers to his Cannes-winning The Tree Of Life—the Amnesiac to his Kid A, in other words—Knight Of Cups unifies the three into a loose and loosely autobiographical trilogy: Where once the Texas filmmaker turned his awed gaze to milestones of national history, like the American pilgrim experience or World War II, he now fixes it on the important events of his own history (or at least what we know of it). Cups, in other words, finds him again shuffling through ancient memories; though set in some glowing approximation of our here and now, the wisp of a plot undeniably recalls chapters of Malick’s life—in particular, his days as a party-hopping screenwriter, circa the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Yes, our most nature-obsessed auteur has set a movie in Hollywood, where sunlight glints off towers of steel and glass instead of trickling through the overhead foliage. Working, as ever, with production designer Jack Fisk (envisioning this modern metropolis again, after Mulholland Drive) and three-time Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, Malick restores a dreamlike grandeur to L.A. His dazed proxy is Christian Bale, reuniting with the The New World director to embody (“play” would be misleading) a hired-gun wordsmith named Rick. Some early narration—the aural wallpaper of a Malick movie—frames the man’s misadventures in folkloric terms, likening him to a prince who fell into a deep slumber. It’s more of a waking sleep for Rick, who spends most of Knight Of Cups hitting pool parties, bedding beauties, wandering conspicuously empty backlots, and taking scenic cruises across California expressways. Occasionally, the empty promises of some studio suit will penetrate the bubble of Rick’s sustained reverie. Other times, famous actors—many starring as themselves—will drift absently into frame, as though we were watching the artiest episode of Entourage ever.

Alternating shots of Bale looking lost in the big city with ones of him wandering a presumably symbolic beachfront, Knight Of Cups sometimes threatens to transform into a feature-length version of the dour Sean Penn scenes from The Tree Of Life, complete with the (sadly autobiographical) suicide of a younger brother. The memory-collage of a story—maybe “symphony” is more appropriate—would seem close to free-associative were it not for the chapter headings (“The High Priestess,” “The Hanged Man,” etc.), named after tarot cards. In truth, actually, the organizing principle is failed relationships: Each movement is marked by the presence of a different squeeze, six of them total, including an ex-wife (Cate Blanchett), an elusive model (Freida Pinto), a wronged old flame (Natalie Portman), and a rambunctious stripper (Teresa Palmer). Are we getting a guided tour through Malick’s little black book? The women are alluring types, not really people—a byproduct of the film’s subjective POV, the way its director fragments performance, or probably both.

Acting in a Malick movie falls somewhere between interpretive dance and really emotive modeling. The director frequently seems more interested in aura than chops, just as his characters—yet another word to be used loosely, at least when talking about the recent work—don’t so much express traits as represent major themes. That’s one reason that To The Wonder fell a little short of Malick’s high bar: The complexities of a failing marriage are hard to convey through his usual balletic means; you need well-rounded lovers, not holograms of memory and feeling. Knight Of Cups fares better, because it’s not a relationship drama, but a portrait of a womanizer bounding from one doomed affair to the next. The love interests make shallow impressions because they’re supposed to. Likewise, Bale’s blankness serves a purpose, too: Rick is narcotized by Hollywood, by empty success and false contentment. The universe keeps trying to shake him from his catatonic state—first literally, with an earthquake; later with a home invasion that leaves him hilariously unfazed—but nothing breaks the spell. (For a while anyway: As in The Tree Of Life, higher power seems to beckon, and not for nothing is the final segment called “Freedom.”)

Malick makes movies that play like no one’s but his own, and that’s partially because his influences often seem anything but cinematic, stretching as they do to literature, classical music, painting, history, and anthropology. Knight Of Cups, which begins with a passage from the 1678 allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress From This World To That Which Is To Come, has no shortage of allusions for adventurous fans to map and trace. But beyond the basic sensory appeals, it offers too few direct inlets for viewers, with Malick viewing his early adult life with much less of the emotional clarity he wrung from his childhood in The Tree Of Life. When Wes Bentley shows up as the aforementioned brother, overshadowed by a disapproving father (Brian Dennehy, more mournful than Brad Pitt was in essentially the same role), the film literally mutes the drama they bring with them, dipping the volume during a rare moment of actual confrontation. The scene makes sense as a memory—we recall the emotion of an old fight, not always the specifics—but it’s also emblematic of how Malick abstracts relationships. Only by projecting details of biography onto these empty vessels do any of the familial interactions take on meaning.

Meaning for us, anyway. No doubt everything in Knight Of Cups resonates with the man who made it; though it’s resulted in films more imperfect than the profound epics (Days Of Heaven, The Thin Red Line) he used to endlessly belabor, Malick’s current period of increased productivity is plainly fueled by personal investment. He’s doing memoir in poetry instead of prose. And if watching a directorial surrogate ghost through his charmed life isn’t exactly relatable, Malick is still firing on all aesthetic cylinders—especially, in this case, when it comes to how he captures his central backdrop. This is among the most striking yet ambivalent visions of Los Angeles put on screen, with buildings looming like silver canyons and golden days bleeding into neon nights. Shooting on everything from 35mm to Go-Pro digital, the director lends the city an alien beauty to go with its alienating culture of wealth, isolating his actors on empty streets and transforming a strip club, of all places, into a kind of makeshift holy space. Malick’s tricks may be aging, but every world still looks new through his eyes.