The establishing shot is one of the least elegant elements of a TV show’s visual vocabulary, a quick-and-dirty shorthand for establishing a scene’s location—even though that scene is, more often than not, actually playing out on a soundstage miles away. (Or, in the case of the former home of Onion Inc. and NBC’s Sean Saves The World, several states away.) And yet there’s a certain beauty in the establishing shot, the shooting location of which is often the only way a viewer can interact with the universe of their favorite show. Visit downtown Minneapolis and you can see where Mary Richards, Lou Grant, and Ted Baxter worked on The Mary Tyler Moore Show; in Chicago’s Edgewater neighborhood, some lucky condo owner sleeps in the bedroom ostensibly shared by the Hartleys of The Bob Newhart Show. Similar sites are scattered across the United States, but the Los Angeles area is chockablock with them—many of which aren’t even standing in for fictional L.A. locations.

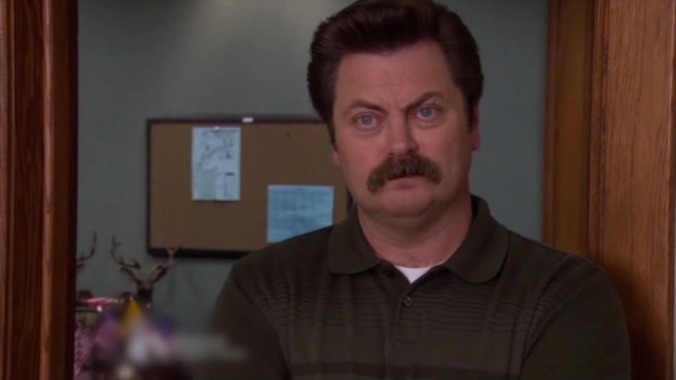

And so began a trip spanning some 20 real-world miles and four TV-world states (Pennsylvania, Illinois, Indiana, and California), encompassing a decade of sitcom history, one loony horror anthology, and a brief stop off at ABC’s old TGIF lineup. With the exception of Pasadena City Hall—which Parks And Recreation portrays as Pawnee City Hall through the photographic trick of never showing the massive heads of Jackie and Mack Robinson—and the American Horror Story “murder house,” none of the buildings we saw that day bore any significance beyond their brush with television stardom. And that’s sort of the idea: The beige exterior of Chandler Valley Center Studios is anonymous enough to pass as a dull office park in Pennsylvania. And there’s enough patina on the Nate Starkman Building to convince viewers that it’s actually the grimy exterior of a bar located just down I-476 from Dunder Mifflin Scranton. These buildings were chosen to play buildings in other places because nothing about them explicitly says “Los Angeles.”

And though that versatility might read as facelessness to some, the L.A.-as-L.A. locations on The A.V. Club’s TV tour still speak to the character of the city. The Rosenheim Mansion featured in American Horror Story’s first season was designed by Alfred Rosenheim, one of the city’s leading architects at the turn of the 20th century. (Further bolstering its destination status: The mansion was the one stop on the tour at which The A.V. Club ran across any other sightseers.) The New Girl loft at 837 Traction Avenue is a mixed-use renovation calling to expat dreamers from within the city’s Art Districts; it’s in one of those lofts that Incredibles director and one-time Simpsons hand Brad Bird reportedly created his short-lived cartoon Family Dog. (Though apartment listings like this one indicate that, even in Los Angeles, you still can’t pay the rent in hopes and dreams.)

Across the decades, Los Angeles and the surrounding area have shaped themselves into a city that’s willing and ready to be shaped into the image of multiple locations around the globe. Now if it could only shape itself into an area that cooperated with Pop Pilgrims 100 percent of the time, we’d be all square.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.