Love, Antosha is a touching, adoring tribute to the late Anton Yelchin

It was a truly random, senseless accident that claimed Anton Yelchin’s life on June 19, 2016. A malfunction with his Jeep Grand Cherokee caused the vehicle to roll backward down his driveway and pin him to a brick pillar and fence; the actor died shortly thereafter. Although Yelchin was only 27, he had already built a strong legacy in both indie and studio films, and his motivations, passions, and conflicted feelings about his own career are considered in the affectionate but even-handed documentary Love, Antosha.

Directed by Garret Price, who took the job after Like Crazy director Drake Doremus passed on it because of his closeness with the actor, Love, Antosha presents an astonishing amount of archival material from Yelchin’s parents and his personal journals, photos, and home videos. Countless moments from Yelchin’s childhood are featured with permission from mother Irina and father Viktor, who abandoned professional figure skating careers in Russia to raise Anton in Los Angeles. The guardians of everything their son left behind, they share with Price the handmade get-well cards he crafted for Irina, footage of Anton goofing around at birthday parties or in the family pool, and behind-the-scenes moments from myriad film sets.

With those components, Love, Antosha crafts an image of Yelchin as a dynamic kid prone to bouts of endless energy and deep introspection. He’s practicing a dramatic Hamlet soliloquy in one clip, gracefully dancing with his mother at a birthday party in another—glimpses of a curiosity about all forms of artistic expression that the documentary will later expand upon. Price then reveals the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis that Yelchin kept a secret from the media but would define the actor we saw grow up on screen.

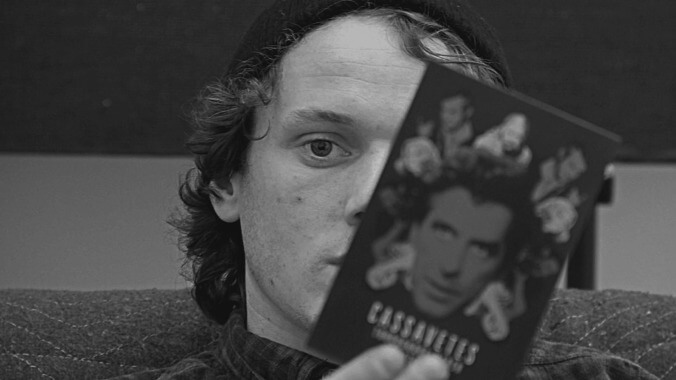

In the 16 years that he worked as actor, from 2000’s A Man Is Mostly Water to 2017’s Thoroughbreds, Yelchin appeared in both Hollywood franchises and indie hits. He often vacillated between roles that either highlighted his slight frame and sensitive demeanor or undermined those very qualities. Think of the openness with which we saw him fall in love in Like Crazy or the brutal way he threw his body around in the Nazi-bashing Green Room; the fragile angst of his starring role in Charlie Bartlett or how his desire for vengeance anchored the Fright Night remake. Price reveals the man behind those contrasting performances by highlighting how Yelchin’s early cinematic education of Martin Scorsese films, French New Wave, and Japanese classics shaped a nearly fanatical pursuit of artistic purity, whether in crime capers like Alpha Dog or big-budget action flicks like Terminator Salvation. And by eliciting reflections from many of the filmmakers and fellow actors involved in those projects— including John Cho, Kristen Stewart, Chris Pine, Simon Pegg, Jennifer Lawrence, and the aforementioned Doremus—Price deepens the understanding of the energy Yelchin brought to a set, a ceaseless desire to learn and to perform.

Their stories about Yelchin the friend and colleague are lovely, heartfelt, and often quite funny, touching on his endearing goofiness and passion for the work. Although they might be slightly repetitive (both Stewart and Lawrence talk about how they re-assessed their acting style once working with Yelchin), they cement his consistency as an ally and confidant. Stewart speaks of the crush she had on him while they filmed 2005’s Fierce People: “He kind of, like, broke my heart,” she says with a smile. Pine recounts the time they spent filming Star Trek Beyond: “It got a little intense for a while,” he says of Yelchin’s increased drug use, before launching into a story about how his costar was so kind that even when Pine fell asleep on him on a boat, Yelchin didn’t move for an hour so as not to wake him up. And similar sentiments are echoed by childhood friends, who recount how Anton’s battle with cystic fibrosis never stopped him from spending time with them, even as his profile grew.

Though clearly an adoring tribute, Love, Antosha allows its subject a sort of complicated humanity that expands our understanding of him, largely by locating a tension between his zealous approach to acting and his increased disinterest in celebrity. Price shows us the notes Yelchin scrawled in the margins of his scripts, with numerous underlines and exclamation points displaying his excitement, his questions, or his uncertainty. With customary zany energy, Nicolas Cage narrates the emails and letters Anton sent to his parents about his deeply researched preparation for various roles, including getting drunk to deliver a more natural performance in Alpha Dog. (“He’d go farther than most people,” says Ben Foster.) The words of letters and journal entries appear onscreen in Yelchin’s handwriting as Cage reads them, and that presentation lets us into the actor’s mind as he put those sentiments to paper. And we also catch glimpses of some of the art that Yelchin created on his own as a musician and a photographer, including a portrait series he shot at a sex club in the Valley and the rock band he was in with childhood friends.

The image that forms of Yelchin is a young man equally committed to acting and to pushing the boundaries of what he could accomplish—not just because of his health problems, which we see take its toll on his physical appearance as he grows older, but because of his resistance to celebrity. (“I wonder how many hits this is going to get, possibly 1,000 hits,” Yelchin sarcastically says to a TMZ reporter following him around.) It’s a familiar story of child stars and the pressures they face as they grow older, but thanks to how fully Price portrays Yelchin, it’s easier than usual to sympathize. What also feels familiar (and especially heartbreaking, given his tragic death) for a documentary of this type is Zachary Quinto’s insistence that Yelchin never seemed quite aware of the respect or adoration he generated from others: “I don’t think he ever let himself know that or believe that,” his Star Trek castmate says.

Price, to his credit, gives Yelchin a voice by featuring so much of what the actor created, but Love, Antosha is too loving of a documentary to allow for Yelchin’s own self-doubt to be the final impression with which viewers are left. Instead, the last few minutes of the documentary emphasize how much Yelchin accomplished in his 27 years of life, editing together brief clips of final projects, including the Shakespeare adaptation Cymbeline, the short film “Court Of Conscience” alongside Jon Voight, and the sci-fi mystery Rememory opposite Peter Dinklage. Yelchin’s variety of projects, his acceptance of any role he fancied regardless of the prestige of the film, was something to be admired and respected, Price says—an extension of how the actor lived his life to the fullest. “I don’t want him ever to be forgotten,” the late Martin Landau says of Anton, and Love, Antosha refuses to let that happen.