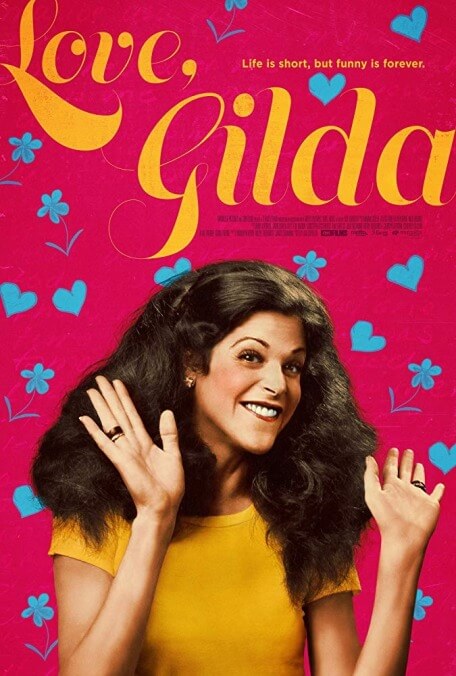

Love, Gilda struggles to summarize the joyful genius of Gilda Radner

Gilda Radner was on Saturday Night Live for five years, during which she distinguished herself with an ebullience that merged the joyfulness of her performance with the truth of whatever character she was playing. Those 106 episodes of the series are all on DVD, and it’s not too difficult to track down some of her other work, like the film version of her Broadway show Gilda Live, or the ill-regarded movies she did with her eventual husband Gene Wilder. But her CV isn’t much compared to other SNL luminaries who might compete for her assured place in the show’s all-time top five performers. Amy Poehler, for example, is closing in on 100 acting credits on IMDB. Dan Aykroyd has over 100, and was also at one point given the leeway to make Nothing But Trouble. Radner, who died of ovarian cancer at age 42, has just 15.

It’s this relative scarcity that makes the documentary Love, Gilda so immediately appealing—and maybe also what makes it feel spread a little thin. In an unobtrusive way, Lisa Dapolito’s film digs around for Radner material that goes beyond all those classic SNL clips, and she comes up with home movies, early performance clips that predate SNL, rarely recirculated talk-show appearances, and even narration, cobbled together from what the movie implies are her personal audio diaries and material straight-up excerpted from the audio version of Radner’s autobiography, It’s Always Something (published a few weeks after her death in 1989).

These materials are assembled into more or less a straight biographical retelling of Radner’s life, albeit with no central narrator beyond Radner, and somewhat fewer talking heads than these types of docs sometimes employ. In addition to select family, friends, and co-workers, Dapolito makes the compelling decision to bring along a group of contemporary comics, mostly from or affiliated closely with SNL, letting Poehler, Maya Rudolph, Melissa McCarthy, Bill Hader, and Cecily Strong go through some of Radner’s old notebooks and journals, often nodding with recognition at her observations, and adding their own thoughts about what they learned from watching her. (Poehler, amusingly self-deprecating, claims that most of her own showcase bits on SNL were simply ripped off from old Radner material.)

Words from a newer generation of Radner-inspired performers help fill a noticeable gap in contributions from the original Not Ready For Prime-Time Players. Only Chevy Chase and Laraine Newman are on hand to talk about their experiences, along with Martin Short (who appeared with Radner in a production of Godspell!) and the eternal poker face of Lorne Michaels. It’s not surprising that Bill Murray doesn’t put in an appearance outside of archival materials, but it’s still disappointing not to see him, Aykroyd, Jane Curtin, or Garrett Morris on hand. For that matter, there isn’t much of a deep dive on the Saturday Night Live clips, many of which would be familiar to any casual student of the show’s best-of reels, and almost all of which feel oddly truncated here, as if testing the limits of fair use. Fair enough if the filmmakers didn’t want to pay a fortune in clip licensing or drown their movie in pre-existing material, but seeing Radner’s genius reduced to highlight reels isn’t exactly revelatory either.

The pared-down performances are especially noticeable because elsewhere, the movie leaves plenty of dead air around home movie footage or even stills, as if lingering on these materials will make them extra evocative. While it’s compelling to hear Radner talk about her family (of her father: “He was the best audience in the world”) or others discuss the psychology of her eating disorder (tacitly used as material for her early and endearing recurring SNL time-filler called “What Gilda Ate”), Love, Gilda doesn’t quite have the heft of a satisfying biography. Some fascinating details both personal and professional, like how she nearly became a homemaker in Canada before her career got off the ground, or the ways she was forced to work around the endless boys’ club of comedy, go relatively underdeveloped.

The most productive thread comes from Radner’s observations about how SNL functioned as an extended adolescence for her, and how that related to being forced to grow up after she left the show. When the film does move past those SNL years and into her struggles with cancer, the stories and footage are inspiring and moving. But the emotional impact is ultimately surprisingly muted; she dies too soon, and the movie ends. Then again, it’s hard to blame anyone for assuming that consistent access to Radner’s voice, in moments both public and candid, would be enough. She radiates such joy, all these years later, that it nearly is.