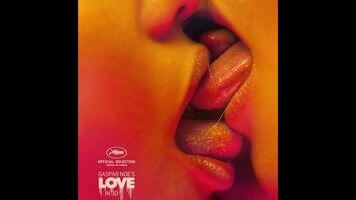

Love is another visually striking trip up director Gaspar Noé’s ass

Working in that time-tested arthouse tradition of combining explicit sex with interminable scenes of people arguing and talking about themselves, Gaspar Noé’s overlong 3-D relationship drama Love unfolds as a series of spats between pigheaded American expat Murphy (Karl Glusman) and his Parisian girlfriend, Electra (Aomi Muyock), presented as flashbacks and dressed up with hardcore sex scenes scored to Erik Satie piano pieces, in which nothing really happens; you could take the sex scenes out, and Love would still be more or less the same film. This is another trip into the director’s ceaselessly self-explaining universe of archetypes, 2001: A Space Odyssey references, and New Age philosophy, and though Noé (Enter The Void, Irréversible) is by turns naïve, juvenile, and clumsily literalist, he is also a filmmaker stubbornly committed to making movies that don’t look or move like anyone else’s. He is confidently original—at least for someone who’s basically an edgy teenager in the body of a middle-aged man.

Naming a protagonist who does everything wrong Murphy and a woman with serious daddy issues Electra is about as subtle as Love gets, extrapolating an ordinary case of male ego (short version: He wants to fuck other women, but can’t stand the idea of her with another man) as though it were teaching Greek tragedy, complete with a scene in which a character explains the central themes of a movie that is exactly like the one the audience is watching. Noé is addicted to self-references: Murphy—who, like the Argentinean-born director, came to Paris for film school, not speaking a word of French—stashes drugs in a VHS case for Noé’s debut, I Stand Alone, and has a scale model of one of the fantasy buildings from Enter The Void; in framing scenes that show him slightly older, he has a young son named Gaspar. There’s a difference between being naked before an audience and showing them your dick, and Noé does the latter—very literally, in close-up and 3-D.

Noé is self-aware enough to recognize that his movies tend to disappear up their own asses; not for nothing is the nightclub in Irréversible called The Rectum. Love frames its own navel-gazing as an experiment in first-person psychological interiority, narrated by Murphy, who is trying to remember Electra while smoking opium on a dreary New Year’s morning. The misogynistic, self-pitying voice-over brings to mind the bitter, alienated narrator from I Stand Alone, though the approach here is perhaps too measured (or too personally invested) to be corrosive. Or perhaps the problem is in the cast, too amateur to emote and talk at the same time; what one wouldn’t do here for the unstable line readings of Enter The Void’s Paz De La Huerta, not to speak of the zip Vincent Cassel and Monica Bellucci put into Irréversible.

What does that leave? The movie’s geometrically striking, intentionally limited style. The camera is presentational and largely static, suggesting movement in the background of graphic novel panels, or, in the rare cases when it moves, the locked third-person of an open-world game. For the most part, there are three kinds of shots in Love (frontal, profile, overhead), which sometimes creates the impression of a moment being coldly sliced, as though by a lab technician preparing a microscope slide. Formal gimmicks have always been Noé’s strong suit, and here he comes up with a simple and effective one, spacing the shots with flickers of black screen in lieu of traditional continuity cuts. Love, a movie with very little to say about relationships and even less to say about sex, is somehow one of the most interesting attempts any filmmaker has made in recent years at conveying the experience of memory.

Love handles sex unimaginatively, with the kind of solemnly static compositions and classical music that let viewers know it’s art. But its use of 3-D to visualize the energy and movement of cosmopolitan nightlife (also a strong point in the opening stretch of Enter The Void) is sometimes dazzling: Laser lights and strobes confuse the visual planes of a nightclub scene; dim apartment interiors recede into the background like illusionistic trompe-l’œil frescoes; and an argument staged in the back of a cab, with Murphy and Electra silhouetted against the moving backdrop of the city street, throbs with claustrophobic immediacy. Ironic that a movie that’s so explicitly about intimacy should only feel intimate when it gets its characters to leave the house.