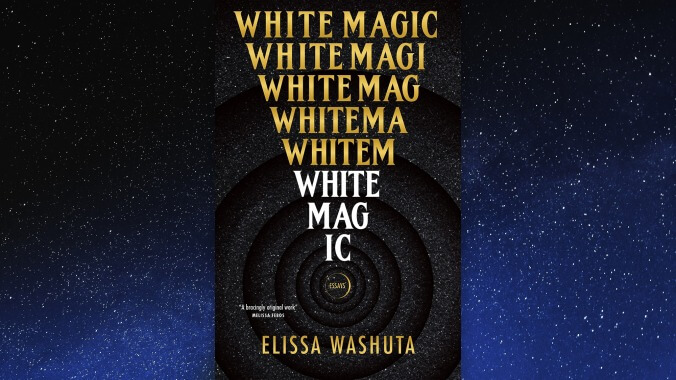

Cover image: Tin House Graphic: Natalie Peeples

You’d think that once someone committed to embodying an archetype of forbidden and mysterious power, they’d relax a little about the whole “black magic” thing. But anxiety about practicing the “wrong” kind of witchcraft permeates occult literature; Of Blood And Bones, a book about using taboo materials like—well, like blood and bones—in spellcraft, opens with an extended introduction reassuring readers that it’s okay to engage with the dark and difficult as well as “love and light.” Elissa Washuta, on the other hand, spends little more than a page dismissing these dichotomies as nonsensical, and racist to boot. Titling her third book White Magic, then, is somewhat tongue in cheek—especially considering its engagement with and exploration of its author’s Native heritage (Washuta is a member of the Cowlitz Indian Tribe). But it does come around to a place of reconciliation and the completion of a cycle, through being splintered by pain that’s hard to articulate in some ways and brutally obvious in others.

Washuta is a modern witch, and her trek through the underworld includes revisiting some humiliating Gchat logs, as well as a deep identification with Stevie Nicks. As with the Fleetwood Mac frontwoman, men are both the source of and a distraction from Washuta’s suffering, and White Magic touches on both addiction and trauma narratives as part of her descent. But it doesn’t live in them. Nor does it live in the critique of cultural appropriation that leads the book’s back cover copy. Instead, Washuta breaks down and reassembles these threads in a series of connected essays, interweaving them with history as well as pop culture artifacts like The Oregon Trail, Friday The 13th, and Pokémon Go that have served as sites of synchronicity and searching in her journey of “[having] my heart broken, and becoming a powerful witch.”

That second part is accomplished through a bit of sleight of hand. Although she does describe a handful of candle spells and one useful four-card tarot spread—all love magic, of course—White Magic is not a how-to manual. It’s too liminal for that. The climactic moment, the burst of supernatural insight, flows through Washuta’s consciousness like the rivers that her ancestors tended for millennia before the white man came and, in his hubris, decided to bend the water to his will. This sense of place and connection to the natural world comes across vividly in White Magic, whether Washuta is describing the verdant forests of the Pacific Northwest or the dust-choked air in Pennsylvania coal country.

But perhaps her most cunning witchery comes in the way Washuta exposes the bones of her writing, teasing the reader with coy notes about the importance of rising action and denouement in the opening paragraphs of essays that subvert those same rules. There’s also the startling clarity of her prose. Take the distillation of the anxiety-ridden hours spent staring at the ceiling ruminating on one’s uncertain future into the pithy “night math.” Her skill at transforming writing clichés and well-worn cultural signifiers—“unfortunately for us,” she writes, Twin Peaks resonates for her as much as it has for other essayists—into fresh insights is alchemical, and the structure of the essays in White Magic subtly immerses the reader in the practice of magical thinking, where there is no such thing as coincidence and repetition is the key to higher states of consciousness.

White Magic arrived in this writer’s life around the same time as a witching-hour obsession spent scouring Zillow wondering if maybe a house back home in Ohio—where Washuta also buys a house in the book—is the way to go. Troubled by the arrival of a book about transition and transformation at a time of similar personal crossroads, I pulled a tarot card and asked what it meant to have an advance reader’s copy hit its target so precisely. King of Pentacles: a card connected to Taurus, the sensual, earthy astrological sign where the sun currently resides. King cards in the tarot are generally associated with men, and Pentacles associated with money; combined, King of Pentacles is a card that emphasizes a methodical and disciplined approach to stability and lasting wealth.

The hard way, in other words, a reminder that nothing worth having comes easy. White Magic works similarly, documenting the messy and painful work of returning from a netherworld of dissociation and self-destruction to be present in one’s own body in all its brokenness and need. For Washuta, that means finding a safe place to finally close the door on the past and be alone, ready for the flare-ups of PTSD that imply that time is not linear, although we perceive it as such. Well, most of us do, anyway—not a witch like Elissa Washuta.