Love, Simon often plays like sweetly progressive, second-rate TV

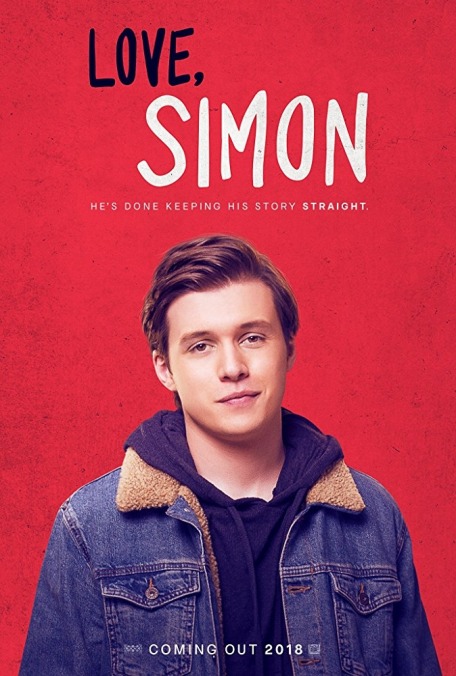

Love, Simon opens with narration from its teenage protagonist Simon Spier (Nick Robinson) explaining, with what seems like maximum presumption, that he’s “just like you.” He proceeds to describe a thoroughly upper-middle-class existence that includes a spacious, well-appointed home; high-achieving yet ever-present and caring parents (Jennifer Garner and Josh Duhamel); an overly art-directed bedroom decorated with perfect self-expression; money and a car for daily iced-coffee runs; and a close cadre of well-scrubbed yet diverse friends who carefully and conveniently self-censor their language to stay comfortably within the confines of a PG-13 rating. He’s just like you, assuming you live in a teen soap or possibly a car commercial.

To the movie’s credit, it’s revealed a little later that Simon is not actually talking to the audience, swapping a rhetorical “you” for a specific one. The explanation of his picture-perfect life, and also the secret he’s carrying with him, is addressed to an anonymous internet pen pal he calls Blue. Simon finds Blue’s email address on a PostSecret-like website where students at his high school upload confessions, and they bond over their common ground: They’re both closeted gay kids. As they share feelings they’ve never been able to express to another person, they develop feelings for each other, even as they remain unsure of who might be on the other end of the email.

That this story is coming from a major studio, with the gay kid depicted as an all-American everyboy and main character, rather than a comic sidekick, represents undeniably heartening progress. Though Love, Simon is much more of a coming-out story than a proper romantic comedy (or drama), its version of that narrative feels fresh, too, depicted as a more gradual process than a single climactic speech.

Robinson, the older brother from Jurassic World, demonstrates considerable range by playing a teenager who isn’t an insufferable bastard this time around. Love, Simon is adept at placing Robinson opposite other actors for sweet, small, affecting scenes—little heart-to-hearts that come from sources both expected and not. The movie is also occasionally deft at composing teen zingers (“Girls don’t want to read your clothes,” Simon advises a hapless frenemy with a weakness for joke tees). But the actual plot is a contrived distraction: Dorky try-hard Martin (Logan Miller) finds out Simon’s secret and, nursing a crush on Simon’s friend Abby (Alexandra Shipp, young Storm from X-Men: Apocalypse), blackmails Simon into nudging the two of them together. This also involves Simon lightly manipulating his pals Leah (Katherine Langford) and Nick (Jorge Lendeborg Jr.), though everyone involved seems weirdly susceptible to Simon’s mild whims, maybe because the characters don’t have much dimension on their own.

It’s hard to get involved in the ins and outs of these relationships when only Shipp boasts much personality, and harder still when the story distracts itself by repeatedly sneering at Martin for quirks that are a hacky screenwriter’s idea of uncool red flags. Get this: Martin is getting really into close-up magic, and his room is decorated with posters of magicians, yuk yuk. While it’s refreshing to see a teen movie willing to leave a straight, white, male character on the sidelines, there’s no dynamism to Martin’s cluelessness and creepiness. It’s just placed in a box and separated from the other, more attractive characters. (Maybe Martin’s parents don’t have time to outfit his bedroom with the tastefully creative chalkboard that surrounds Simon’s bed.)

Similarly, the pair of bullies who say homophobic garbage to the school’s one out gay student seem to operate in a vacuum, emerging only to be immediately and thoroughly upbraided by a no-nonsense teacher in a key scene. There’s little social texture to Simon’s school: Characters pop in and out at convenience, hindering the movie’s ability to connect its most affecting individual scenes. (It stumbles over the school-year structure that Lady Bird uses with uncommon grace, and has the misfortune to boast a far less entertaining glimpse at teen musical-theater subculture).

Love, Simon may not as presumptuous about its class milieu as it initially seems, but there’s a pervasive plasticity that undercuts the sincerity. It’s a feature film with the thin gloss and one-thing-after-another rhythm of a pleasant but lightweight TV show, which makes sense, as director Greg Berlanti is the current comics-to-show czar of The CW, and screenwriters Elizabeth Berger and Isaac Aptaker—adapting a YA novel by Becky Albertalli—have worked extensively in TV. Love, Simon is touching as a gesture. As entertainment, it’s nothing Degrassi hasn’t done better.