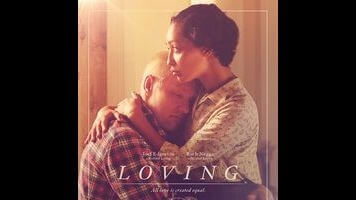

Loving is a crime in this undramatic dramatization of a famous court case

Not all trailblazers live exciting or extravagant lives. Some are just ordinary people, gently fighting for their rights and provoking progress through their steadfast refusal to accept the injustice of their circumstances. With Loving, writer-director Jeff Nichols (Take Shelter, Mud) lionizes two such everyday heroes: Richard and Mildred Loving, whose nearly decade-long battle to legalize their interracial marriage in the state of Virginia went all the way to the Supreme Court, bringing to an end anti-miscegenation laws. Nichols doesn’t much embellish this true story, instead simply observing two lovers standing their ground on what will slowly become the right side of history. But while one would have to be an unabashed bigot not to be moved by the Lovings’ plight, concluding that it’s not so easily dramatized requires no such prejudice. Quiet dignity in the face of adversity doesn’t make for an enthralling couple of hours.

Nichols has always excelled at setting a scene, at filling in the flavor and texture of his rural American environments. So it’s hardly surprising that Loving’s best moments are its earliest ones, when the filmmaker is establishing the simple, happy life white bricklayer Richard (Joel Edgerton) shares with his pregnant sweetheart, Mildred (Ruth Negga), who’s of black and American Indian heritage. It’s a small paradise of mundane rituals: afternoons spent gambling on dirt-road drag races, evenings spent dining and drinking with friends, and—in an image Nichols keeps returning to—workdays spent setting the foundations of houses, a skill set Richard plans to put to good use building a home for Mildred. But an ominous tension hangs over this blissful opening passage, even before the two lovebirds sneak off to Washington, D.C., to get hitched in secret. Because their marriage is forbidden in Virginia, it isn’t long before authorities are kicking down their bedroom door, locking them up in the local jailhouse, and forcing them to exit the state, under threat of prison time.

Loving unfolds over several years, from 1958 forward, as Richard and Mildred raise a family in D.C., while making regular, clandestine trips back to the relatives—and life—they’ve left behind. Since so much of the movie is about conveying the emotional duress of people suffering under an unjust law, Nichols was wise to secure two terrifically subtle performers, capable of conveying a wellspring of feeling through nothing but their eyes and mannerisms. Edgerton, who played a similarly laconic working-class character in the director’s recent Midnight Special, portrays Richard as both an intensely private man, shrinking from the media attention their case eventually attracts, and a deeply sensitive one, carrying the full burden of the Lovings’ ordeal on his broad shoulders. (There’s maybe no actor working today better at physically expressing the depths of inexpressive characters.) Negga, who’s probably best known for her recurring roles on Preacher and Agents Of S.H.I.E.L.D., exhibits a similar range in a low-key register—wilting with melancholy away from her family, beaming with cautious optimism once the ACLU decides to get involved.

Nichols’ staunch refusal to glamorize the Lovings, his insistence on depicting them as normal people making unwitting history, is admirable in theory. This is not a movie that hands its leads big speeches or encourages them to make these real-life people larger than life, like the noble subjects of some grandiose biopic. At the same time, Loving arguably goes too far in the opposite direction, committing so hard to the Lovings’ fundamental ordinariness that they end up looking less like characters than paradigms of American decency and perseverance, defined only by their struggle. It doesn’t help that Nichols stacks the audience-sympathy deck in small but still unnecessary ways. Assuming, perhaps, that viewers need a specific face on which to project their outrage, the movie casts Marton Csokas as the cold-hearted sheriff, delivering a supervillain monologue about the importance of segregation. And Nichols abuses his own talent for quotidian detail by zeroing in on pocket-sized proof of the big city’s inhospitality—dogs rooting through garbage; a single, sad tree planted in concrete—without explaining why the Lovings had to move to D.C. after leaving Virginia. The point is that the two should have been allowed to live wherever they want, not that where they did end up living was intolerable.

Loving eventually arrives upon its historic court case, with a very distracting Nick Kroll as the pro bono attorney fighting to get them before the Supreme Court. This is the point where characters start saying things like, “You realize this could alter the Constitution Of The United States,” threatening to transform the movie into a better-directed version of one of those stodgy, social-issue TV dramas like Gideon’s Trumpet. But Nichols keeps the focus on the Lovings themselves, enduring in slow motion. “You knew better,” Richard is told, by everybody from his midwife mother to his black friends to that dastardly lawman, and there’s power in the couple’s common-sense resistance to conventional wisdom: They love each other, and they’re not hurting anyone, so why listen when friend and foe alike tell them to give up? Loving makes the uncontroversial case for Richard and Mildred as accidental revolutionaries, implicitly tracing a line from their hard-won victory to recent triumphs in the ongoing battle for marriage equality. But even those inspired by the Lovings’ story might acknowledge a tough truth: Watching two people patiently wait for the world to change, reacting to the occasional good or bad news they receive, is not the stuff of crackerjack drama.