“Talk to people, it’s good for you!” Bill Bryson’s wife, Catherine, tells him early in A Walk In The Woods, as they attend a funeral he wanted to avoid. “I don’t like talking to people,” he grumps back at her. And so the film’s theme is established, in a way appropriate to the rest of its content: in the most graceless, blunt, tell-don’t-show way possible. Bryson, a successful non-fiction writer who uses humor to address science, travel, and linguistics, is portrayed in the early going of A Walk In The Woods as utterly humorless, a curmudgeon wrapped up in his own sullen mind. And it doesn’t help that everyone around him—a TV morning-show host who asks Bryson dim-witted questions, a sporting-goods salesman played by Nick Offerman in a cameo, the miserable widow at that funeral—heightens his disaffection with the world by being immune to any cranky jokes he does make. The film version of Bryson is a self-absorbed jerk, but then, so is everyone else in the film. No wonder he wants to get back to nature, and away from people, by hiking the 2,200 miles of the Appalachian Trail.

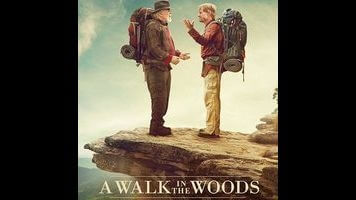

Robert Redford—who stars as Bryson and produced the film based on Bryson’s book of the same name—has been trying to get A Walk In The Woods made for the last decade, and he shows his affection for the character and the material by playing Bryson with a warmth that isn’t on the page. The story setup suggests Planes, Trains & Automobiles redux: The self-sufficient Bryson, who’s lived in England for decades, attempts to reconnect with America via a five-month hike, but the only partner he can find for the trip is his long-estranged, out-of-shape, fundamentally lazy old buddy Stephen Katz. (Nick Nolte plays Katz with a lifelong-smoker’s rasp that sometimes turns querulous; he sounds like a sack of gravel with a squeak toy in it, being dragged along a rough road.) The two men have a distinct straight man/comic bumbler dynamic. But while their story is cluttered with fitfully funny sequences hitting a wide range of tones, it eventually turns sentimental, with them renewing their bonds by dismissing the rest of the world. Instead of the sloppy comedy it resembles, it becomes a sloppy uplift drama, as Katz comes to terms with his failings, and Bryson finds someone he actually does like to talk to.

In spite of Bryson’s gentle tolerance for Katz and all the other obstacles on his road, the script still has an off-puttingly sour contempt for the world. Bryson was in his 40s when he attempted the trail; Redford is a well-preserved 79, and Nolte is 74, which makes A Walk In The Woods feel more like an irascible Grumpy Old Men-style senior-citizen outing than the midlife-crisis movie it seems to be aiming for. And Redford can’t compensate for the ugly, snide streak running throughout the entire film, especially when it deals with women. Kristen Schaal pops up as a trail-walking harridan so arrogant, grating, and leech-like that Katz suggests murdering her. Katz eagerly, humbly romances a large lady played by Susan McPhail, but sneers to Bryson behind her back that she’s “got a beautiful body… buried under 200 pounds of fat.” And when her violent husband reacts to her philandering, Katz moans about the malign coincidence that somehow put him in the same town as the only other man in the world willing to bed such a porker. Catherine is a boring nag who spends her few moments in the film putting Bryson down and holding him back. (The character’s only saving grace is that Emma Thompson plays her by laughing though every dire proclamation she makes about why Bryson shouldn’t take the trip. She makes the character ridiculous, but that’s better than being shrill.) Even an unseen woman from Bryson and Katz’s shared past is targeted, with a gag about how women who aren’t pretty, funny, or rich had better at least be slutty. Only Mary Steenburgen, as a blandly saintly motel owner, gets off without a few gloatingly misogynistic comments thrown at her, and then only because she has no significance in the story.

Even when the film isn’t dealing with women, it’s contemptuous of the world in a way that rapidly becomes one-note and tiresome. Like any men-behaving-badly movie (the work of Judd Apatow, say, or Adam Sandler), it piles on the hateful behavior to throw the eventual turnaround into a starker light, but brings much more conviction to the boys-will-be-79-year-old-boys antics than to the damp squib of an ending. Which would be fine if the pre-uplift shenanigans were funny. But when the film isn’t dismissing the world as a cesspit of twerps, the humor is limp at best, summed up by a pratfall into a river, or a diner sign that apologizes, “Sorry, we’re open.”

Based-on-a-true-story films about people rediscovering themselves on long walks have gotten a lot of play recently: 2014 saw two of them, the Cheryl Strayed story Wild and the Robyn Davidson story Tracks. But both of those films were more about solitary journeys and personal development, and about what happens to a life when all the inessentials get peeled away. A Walk In The Woods could stand to peel a few things away itself. On the rare occasions when it sticks to Bryson and Katz reconnecting, it manages some pleasant, almost authentic moments. But they’re padded with so much lame, flailing snottiness that they’re hard to find. Maybe there’s a beautiful movie hidden under here somewhere, but Katz’s lady-friend isn’t the only thing disguised by flab.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.