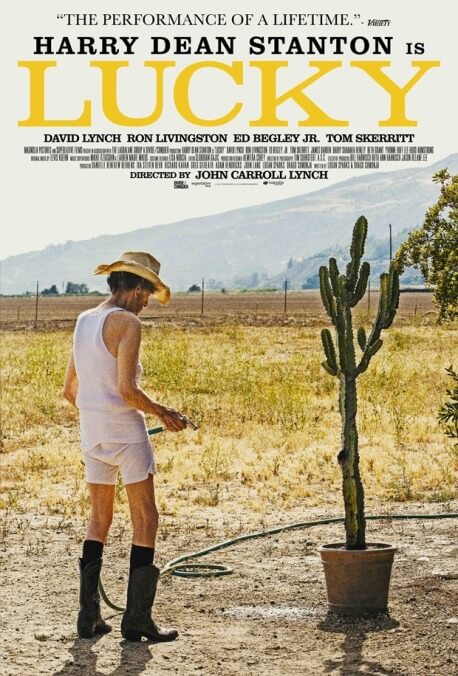

Lucky is Harry Dean Stanton’s accidental but ideal swan song

Harry Dean Stanton’s death not even two weeks ago can’t exactly be called unexpected, given that he was 91 years old. Still, it’s almost as if he deliberately timed it to coincide with the release of Lucky, a film expressly about coming to terms with the prospect that you will soon no longer exist. The directorial debut of ace character actor John Carroll Lynch (Marge’s husband in the movie Fargo, the creepiest suspect in Zodiac, etc.), this lightly eccentric, virtually plotless meditation on mortality would likely have attracted attention under any circumstances—indeed, even had it turned out to be terrible—simply because it offers Stanton his first leading role in a feature film since 1984’s Paris, Texas. (First-time screenwriters Logan Sparks and Drago Sumonja reportedly conceived it with him in mind; it’s hard to imagine who else they might have turned to had he said “No.”) So it’s a remarkable gift to fans and cinephiles that Lucky serves as a first-rate showcase for its star as well as an ideal swan song. The man couldn’t have gone out any better.

Echoing the structure of Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson (with which it shares an actor, Barry Shabaka Henley—his avuncular character runs a bar in that film, a diner in this one), Lucky depicts its titular protagonist’s mundane routine over the course of several consecutive days. He rises, does some quick yoga exercises, walks to the diner for some coffee (doing the crossword while there), buys milk and cigarettes from a local convenience store, heads back home to watch game shows, and eventually winds up at his favorite bar among other regulars (including David Lynch, Beth Grant, and James Darren). One day, the blinking 12:00 on his coffeemaker causes him to keel over, and while his doctor (Ed Begley Jr.) doesn’t find anything in particular amiss, the incident seems to belatedly stir in Lucky an awareness that time might be running out for him. What’s more, every stranger he now encounters, from a life insurance salesman (Ron Livingston) to a philosophical ex-Marine (Tom Skerritt), inspires further thoughts of the coming void.

It takes a great actor to make such potentially heavy material feel liberating rather than oppressive, and Stanton is up to the task. The movie gives him one showstopping setpiece, performing a quavering rendition of the Mexican folk song “Volver, Volver” at a kid’s birthday party, but his performance is mostly a gradual, subtle, interior journey toward acceptance of the unknown, cannily working against the narrative’s deliberate repetition. He’s also self-confident enough to allow each member of the supporting cast a moment to shine, allowing for amusing digressions that range from a blow-by-blow description of Deal Or No Deal (Lucky’s verdict regarding watching the show: No Deal) to David Lynch’s earnest tribute to a runaway tortoise. Even when Sparks and Sumonja’s script gets overly aggressive about pushing the mortality theme—and it does get laid on pretty thick toward the end—Stanton’s lifelong penchant for underplaying keeps Lucky from flatlining. It’s a pleasure just to watch him silently regard the world, frail but still vital. Even if it’s also a bummer to think about the sizable hole in the world where he used to be.