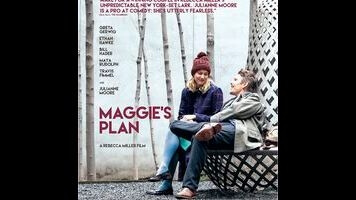

Maggie (Greta Gerwig) has a plan all right, and it just might be crazy enough to work. Two years after wooing a married man out of his marriage, she’s found trouble in paradise and a whole mess of second thoughts. If only there was some way she could… give him back, effectively rebuilding the home she’s wrecked. That’s the gist of Maggie’s Plan, a comedy that proves that an appealing cast (Gerwig, Ethan Hawke, Julianne Moore) and a wonderful premise are no guarantee of big laughs. In this case, the problem might be writer-director Rebecca Miller (Personal Velocity, The Ballad Of Jack And Rose), a filmmaker with little experience in the field of fizzy entertainments. Watching her labored attempt at one, you can’t help but wish that it were, say, Gerwig and her romantic/creative partner, Noah Baumbach, tackling this same material.

In fact, the movie often plays like off-brand Baumbach—or, at the very least, like some generically genteel Manhattan yukfest, opening as it does with a blare of old-timey jazz and set as it is against a New York of bookstores, brownstones, and liberal-arts campuses. Maggie, an administrator at The New School, is ready for motherhood but not partnership; she has a donor lined up in “pickle entrepreneur” Guy (Travis Fimmel). But then Maggie meets and falls for Professor John Harding (Ethan Hawke, adding another wordsmith to his growing portfolio of them), a “ficto-critical anthropologist” trying to reinvent himself as a novelist. One divorce, second marriage, and newborn later, Maggie finds herself unhappily tending to the children (not just her own daughter but also her step-kids) as her husband labors endlessly on a book he might never finish. And so she begins to conspire with his ex-wife, the Danish academic Georgette (Julianne Moore in an Isabella Rossellini role), to restore the status quo.

Maggie’s Plan, in other words, is a riff on a classic Hollywood genre: the comedy of remarriage, in which estranged spouses are drawn back together, usually by screwball circumstance. The wrinkle, improbable and theoretically irresistible, is that it’s the proverbial other woman who’s playing matchmaker with the separated lovers. For that concept to work, though, the film needed a force of comic mischief at its center. Maggie is more like the diet version of the irrepressible NYC types Gerwig often plays; she has all the poor judgment but none of the loopy charm of a Frances or Violet. The movie keeps taking her to task, often through the voice-of-reason pissiness of the best-friend character, played by an unusually unfunny Bill Hader. This isn’t a bad idea on paper either. How many romantic comedies, after all, actually acknowledge exasperating behavior as exasperating? But Miller is so busy scolding Maggie for her selfishness that she never lets her heroine really throw herself into the eponymous scheme. It’s a zany scenario, detrimentally downplayed.

As a result, Maggie’s Plan feels caught in a kind of dramedy dead zone, too broad to work as a straight love triangle and too restrained to do wonders with its high concept. The fact that John’s field is made up and pretentious-sounding is the film’s idea of a fully formed joke, while someone describing the word “like” as a “language condom” is what passes for a bon mot. (Beware the dialogue movie with mediocre dialogue.) If there’s a takeaway here, it’s that the big transitions we think we want—be they from single life to domesticity, academia to fiction writing, or dreary melodramas to Woody Allen imitations—aren’t always the ones that actually suit us. Which is to say, not every reinvention takes, even when you have Greta Gerwig in your corner.