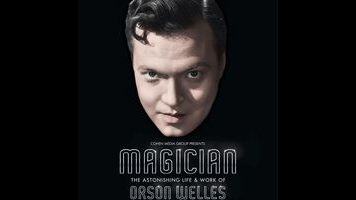

It truly was an astonishing life. But with so much written and filmed about the great talent that was Orson Welles, it’s tempting to wonder if there’s anything left to say. Of course there is: Even the most argued-over artists can be approached from a fresh perspective, and Chuck Workman’s documentary, interestingly enough, brings the man who was Charles Foster Kane (and so much more) into focus by being rather square.

For a number of years, Workman has been one of the go-to guys for the Academy Awards telecast, cutting many of their montages. He’s perfected a style that, at its best, uses glancing superficiality as a means of digging deeper into the subject at hand. Magician is, on the surface, a clip show par excellence, using numerous scenes from Welles’ movies, video of his copious TV chat-show appearances, and footage shot behind-the-scenes during his time with the Federal and Mercury Theaters. (How tantalizing to see even glimpses of the famed Voodoo Macbeth, a 1936 Shakespeare production Welles directed with an all-black cast.)

Workman also throws a number of talking heads into the mix: biographers Joseph McBride and Simon Callow, critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, Welles’ romantic and artistic partner Oja Kodar (effusively holding court about their time together). Some of the interviews look like they were shot recently, others many years ago (probably for other projects or archival purposes) to be resurrected as need be. Most of the footage the director uses can be found elsewhere (like the treasure trove of YouTube), so to a Welles aficionado the doc may seem like well-trod ground. But there’s real power in the way Workman (also the sole credited editor) cuts all the material fleetly and acutely together.

Different interviews with Welles are used to put the man in conversation with himself at different ages (a similar tack to the great recent HBO documentary Six By Sondheim). This works especially well to puncture some of the tales Welles spun about his filmmaking misadventures, like the time studio head Harry Cohn purportedly sent him a large sum of money, as quick-fix support for a theater production, in exchange for the story idea that eventually became The Lady From Shanghai. But Workman’s deeper point is that this fabricative sleight-of-hand was a crucial, and essentially indefinable, part of Welles’ process and mystique.

A true magician never reveals his secrets—perhaps, in part, because he himself can’t quite pin down the alchemy that results in genuine artistry. It’s enough for Workman to simply assemble a patchwork of Welles in his myriad incarnations (as the hearty Falstaff in Chimes At Midnight; as an arched-eyebrow spokesman for Paul Masson wine; as The Third Man’s cynical Harry Lime; as a sharp, vital youth and a sharp, frail elder) and allow the many faces to confirm, contradict, and, ultimately, speak for themselves.