Trying to make sense of Mission: Impossible, Hollywood's most perplexing spy franchise

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to untangle the complex twists, turns, and backstories of the Tom Cruise films and the Peter Graves series

WTF is the IMF? The answer to that question, like many aspects of the long-running Mission: Impossible franchise itself, can be convoluted, elusive, frustrating, and rewarding, in equal measures. A secretive and enigmatic espionage agency, the Impossible Mission Force has served as the anchor for the Mission: Impossible TV series in the 1960s, its two-season 1980s-era follow-up and, of course, the seven and counting feature films led by Tom Cruise’s Ethan Hunt.

Unlike more clearly defined pop mythologies, continuity within both franchises and within the individual films themselves can be as impenetrable as the IMF itself. So just in time for Mission: Impossible—Dead Reckoning Part One, The A.V. Club chooses to accept the mission to decipher at least a portion of what the IMF is. Cue the Lalo Schifrin music and light the match…

TV viewers accept their mission

Producer Bruce Gellar launched the original Mission: Impossible TV series in 1966, marrying the then-red-hot spy trend sparked by the James Bond movies series with the stylish, clockwork procedural aspects of heist thrillers like The Asphalt Jungle and Topkapi. Gellar took a minimalist approach when defining both the IMF and its characters: dialogue, backstory, and the agents’ inner and off-duty lives were given minimal attention. What mattered was the urgent, tense, step-by-step nature of the action, the unforeseen complications the agents encountered, and the innovative solutions they arrived at on the fly.

Among the precious few facts hinted at about the IMF’s origins was that it was founded by Dan Briggs (Steven Hill) during his service in the U.S. Army’s intelligence division at some point during World War II and/or the Korean War. During his service, Briggs, a lieutenant colonel possessing a Ph.D. in analytical psychology, established a team of covert operatives that took on complicated missions for the war effort. After some period of dormancy, Briggs was tasked with reviving the organization as the IMF to help the government achieve its Cold War containment strategies and broadening its parameters to take on corrupt regimes, political skullduggery, organized crime, Nazi revivals, and more.

In its postwar incarnation, the IMF was so faceless and off-the-books that if any mission went awry and any agents were captured or killed, they and their actions could be disavowed by its director. The deep-pocketed geopolitical force that assembled the IMF at the series’ outset was always strongly implied to be the United States; the missions—which were largely international, although increasingly domestic as the series developed—were deemed so dangerous and politically volatile that agents were given the option of refusing the assignment. That the prerecorded message of outreach self-destructed a few moments after being played reinforced how sensitive and damaging the information conveyed might be if intercepted by the wrong hands.

The IMF takes spycraft to high-tech heights

The franchise’s title efficiently summed up just how thorny IMF assignments were: seemingly impossible yet, with the right combination of cunning, tech tools, and carefully crafted big cons, nevertheless doable. To accomplish these, the IMF typically relied on elaborate schemes akin to large-scale confidence games designed to lure in their unsuspecting nemeses and trick them into providing the means of their undoing. As a result, most IMF agents are adept at assuming fake cover identities, including regularly resorting to extravagant makeup and prosthetics.

Intriguingly, as the gadgetry and hardware of other film and TV spy series grew more fanciful and grandiose, the IMF largely stuck to an arsenal of technology that felt only a step or two away from what would be possible in the real world.

Mission leaders like Briggs and, later, Jim Phelps (Peter Graves) were largely given carte blanche in their choices of agents, methodologies, and equipment when it came to tackling each assignment, drawing from various specialists with the skill sets necessary to achieve the objective. The agents varied, and could be as enigmatic as the IMF itself, like Rollin Hand (Martin Landau), a theater arts master of both magician-style misdirection and elaborate disguise, or as high-profile as supermodel Cinnamon Carter (Barbara Bain), whose fame and jet-setting lifestyle offered her easy entry into sophisticated environs.

Missions also relied on high-tech wizards like Barney Carter (Greg Morris) who created the immersive environments and hands-on fabrications necessary to make IMF ruses seem real, and low-profile operatives like Willy Armitage (Peter Lupus), whose unusual strength and low-key demeanor allowed him to perform key tasks while drawing scant attention. Such regular players are supplemented by additional agents who rotate in and out of missions, and one-off “guest” agents recruited for specific abilities necessary for each particular mission.

When friends are foes, and vice versa

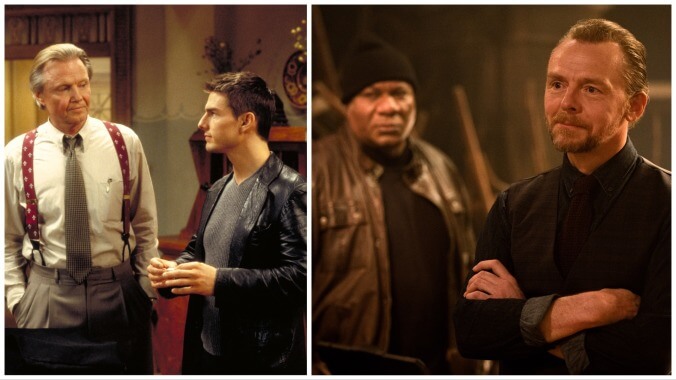

The TV series’ mix of regulars and revolving-door agents would be carried over into the Ethan Hunt era. It should be noted that it’s unclear if the film franchise is set in the same continuity as the TV franchise, with two different Jim Phelps at the core of the confusion: Peter Graves’ noble incarnation of Phelps was the stalwart for the bulk of the TV runs, while Jon Voight’s Phelps in the 1996 franchise-launcher is a duplicitous, self-serving betrayer. It’s never been clarified if the two Phelpses are one and the same, perhaps father and son, or two different agents operating under the Jim Phelps cover identity. In the world of the IMF and Hollywood melodrama, any of these options are plausible.

As Cruise’s Hunt steps into the role of IMF leader, once again a rotating cast of agents is assembled for each outing on a mission-by-mission basis. The most durable regulars are Luther Stickell (Ving Rhames), the once-disavowed computer specialist, and Benji Dunn (Simon Pegg), the technician and field agent with a facility for crafting the IMF’s increasingly realistic disguises. The force also occasionally recruits, even strong-arms, temporary agents, like the glamorous master thief Nyah Nordoff-Hall (Thandiwe Newton), the rogue assassin Ilsa Faust (Rebecca Ferguson), and the prestigious pickpocket known as Grace (Hayley Atwell) into service.

While it still dabbles in some smaller-scale operations, Hunt’s IMF typically takes on missions with world-altering—even potentially world-destroying—stakes, often in the realm of nuclear- and bio- and cyber-terrorism. If there are consistent flaws in Hunt’s IMF, they are a lack of consistent leadership (the role of director seems to be ever handed-off to new and sometimes less capable hands), the increasing encroachment of political and bureaucratic interference in its operations, and a disturbing tendency to be infiltrated by treacherous forces willing to betray the IMF in pursuit of their own agendas. As more and more entities become aware of the IMF’s existence, the more impossible its missions become (which, of course, is part of the on-screen fun).

Lastly, there’s one intriguing thread from both the TV series and the films that is tantalizingly ripe to be tugged at: the longstanding insinuation that many, if not all, of the regular agents became involved with the IMF as a result of a criminal past of one sort or another, perhaps seeking absolution or redemption for past sins. The notion that in the spirit of serving their better angels, Ethan Hunt and his cohorts actually do choose to accept these impossible missions makes their exploits all the more heroic. As more and more entities become aware of the once-shadowy IMF’s existence and its agents’ complicated histories appear poised to come back to haunt them, the more impossible its missions become. Which is why, despite the impossible task of knowing everything there is to know about the IMF, audiences keep coming back decade after decade.