The spokesperson for this idea is Soraya, a tanned sexagenarian who talks eloquently about her gender dysphoria and points out that there is a huge difference between wanting to dress up (or reshape) as a woman and living as one for the rest of your life. It’s a gap wide enough to easily swallow up the naïve or otherwise unprepared. Transgender women and cis women both face fantasy ideals of youth: There’s immense pressure, some of it self-applied, to ward off the signs of aging.

Another sobering subtext: It becomes clear that for many of these subjects, the focus on either flattering or outrageous fashion choices and crafting unique, larger-than-life personas (e.g., the drag performer “Queen Bee Ho”) does not exist outside the spheres of work and money. If anything, they’re intimately tied together, and often in compromising ways. Performing as a drag queen is one thing, but many of the film’s characters also work as prostitutes. This places their liberation in a complicated new context.

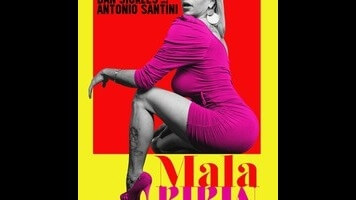

Mala Mala is loosely structured: It cuts back and forth between its different stories without forcing a sense of connection, although one emerges naturally out of the efforts of Ivana and others to lobby the country’s legislature to change the rules about employers being allowed to discriminate against LGBT workers. The outcome of this campaign gives the film a heroic arc, and yet amid all the images of celebration and joyful physical abandon—including a showcase solo dance performance that functions as a kind of climax—the most lingering images are the ones depicting daily routines. The downtime points away from difference and towards a shared continuum of human experience.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.