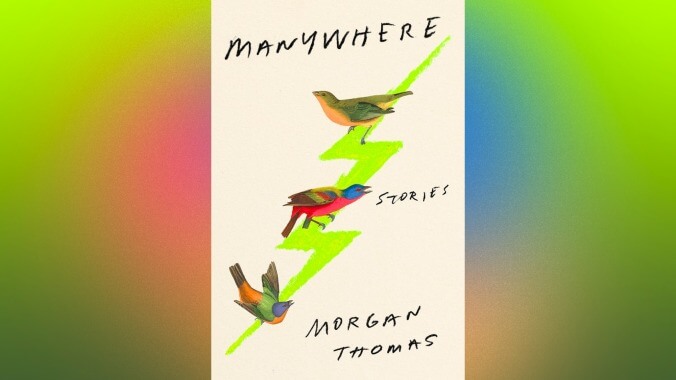

Queer characters are inspired by the past in the enchanting short stories of Manywhere

Connections formed across the decades make up the core of Morgan Thomas’ debut short story collection

In her 2009 review of Italo Calvino’s The Complete Cosmicomics, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote, “The summer reading I like best is either a lovely, long, fat novel to lie down with and get lost in, or a collection of stories, like a basket of summer fruit, to savour one or two at a time.” Manywhere, Morgan Thomas’ thorny debut short story collection, is a basket of tart winter fruit. In their stories, vampires escape gothic boarding houses, fathers watch snakes have sex, and trans elders reach through history to comfort young trans people. Manywhere explores the way history thwarts attempts at connection, and while some of these stories stumble as their narrators become lost in wonder, just as many enchant.

In the opening story, “Taylor Johnson’s Lightning Man,” a young queer person attempts to contact the ghost of Frank Woodhull, but the two can only meet in the conditional future tense. According to multiple New York Times reports from 1908, Woodhull was a woman who dressed and passed as a man. (Describing characters in this collection is fraught. Their gender is murky, as is the documentation, which often strips them of their agency.) Thomas writes Woodhull as a religious icon who haunts the narrator; such intergenerational meetings between trans and trans-adjacent figures form the core of Thomas’ collection.

The narrator of Shola von Reinhold’s 2020 novel, LOTE, has a word for these intergenerational relationships: “transfixions.” The narrator of LOTE is enraptured at discovering the existence of Hermia Druitt, a Black artist who ran around with the Bloomsbury Group. Hermia is an invention of von Reinhold, similar to Thomas’ occasionally invented historical figures.

Thomas ends many of their stories using the future tense, dwelling in one moment while looking forward. At the end of “Surrogate,” for example, the omniscient narrator remarks, “Occasionally, in those deep summer days, those petroleum days, she will forget the child was discharged. She’ll be certain the child died, and she will briefly cry.”

As in Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman, a classic film about queer archives, these characters are obsessed with the ghosts of history. They struggle to make sense of the past and rage for inspiration. “My girlfriend, Reed, says I’m obsessed by them,” one narrator says of their historical crush, “and I do think of myself sometimes as a sort of reincarnation.” This intergenerational kinship is complicated by nostalgia, guilt, and a lack of historical record. Many of the stories cite real or imagined documents. “Taylor Johnson’s Lightning Man,” “The Daring Life Of Philippa Cook The Rogue,” and “The Expectation Of Cooper Hill” all alternate between such documents and first-person narration. Though the archival text sometimes lacks the shimmer of Thomas’ contemporary-set prose, by projecting their characters desires’ onto sketches of historical figures, Thomas has created their own archive.

The narrator of “The Expectation Of Cooper Hill” grapples with their great-great-grandmother Sylvia’s racist past by writing an essay based on her experiences as a midwife. “Whatever came later, I like to think they started as friends,” the narrator writes of their great-great-grandmother, who was white, and her relationship with a fellow midwife, Aunt Paulina, who was Black. Jealous of Paulina’s success, Sylvia plants savin on Paulina, letting her take the fall for performing abortions. The story ties together an intricate web of complicity and admiration. In the end, there is no denouement and the narrator is left harboring a bitter taste.

Not all of Manywhere’s stories are so beholden to the past. One of the most powerful stories in the collection is the contemporary-set “Bump,” in which Len, a trans woman, wants to have a child with her lover, a married cis man. Len’s lover instead has a child with his wife. Len decides–in a fever dream–to buy a baby bump, which she begins wearing outside of the house, passing as a pregnant cis woman. “People think contentment is a gentle, warm thing, like bathwater, that needs only occasional replenishing to keep it from turning slowly tepid. In my experience, contentment often requires more ruthless and more immediate defending,” Len says. These moments, where Thomas leans into the ways people swim in their loneliness, eviscerate neatly held beliefs about happiness. They remind us how the past was once the present, open to all possibilities until one choice flooded the horizon.

Author photo: Ezra Carlsen

Grace Byron is a writer based in Brooklyn. She used to make films. Her writing has previously appeared in Observer and she tweets at @emotrophywife.