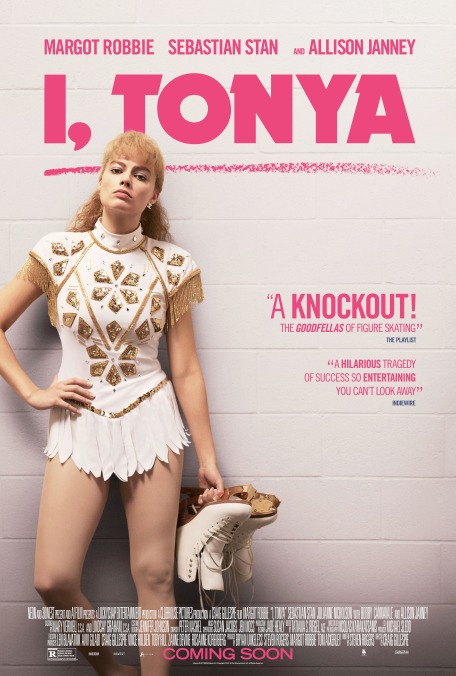

Margot Robbie skates around the diet-Scorsese tricks of the Tonya Harding biopic I, Tonya

From the opening minutes of Craig Gillespie’s unreliably narrated, glibly entertaining biopic I, Tonya, it’s clear that Margot Robbie has disappeared into the role of disgraced figure skater and pop culture punching bag Tonya Harding. It’s not a precise imitation: However hard the wardrobe and makeup teams have worked to deglamorize this glamorous Hollywood star, she still doesn’t look much like the person she’s playing—a truth reinforced by the obligatory, closing-credits appearance by the real Harding, conquering the ice in archival footage. But as she wraps her mouth around a cigarette, a cornpone accent, and some well-delivered profanity, Robbie channels the antagonistic, take-no-shit attitude of her infamous “character,” while adding notes of disappointment and even dignity missing from every headline or Hard Copy treatment of The Tonya Harding Story. In the process, the actor wrestles a rare role worthy of her abilities from an industry that’d just as soon keep her in bubbles.

Harding is best remembered today, by those who remember her at all, for the scandal that ended her career: the 1994 kneecapping of rival Olympic competitor Nancy Kerrigan, orchestrated by Harding’s ex-husband, Jeff Gillooly, and her bodyguard, Shawn Eckhardt. Devoting much of its second half to what it calls “The Incident,” I, Tonya flirts with the thesis that Harding’s downfall was a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy, the inevitable result of being told from the start that she didn’t belong. To the rest of the figure skating world, Tonya was an interloper: the “white-trash” tomboy dropout who made her own outfits, performed to ZZ Top, and cursed a blue streak at anyone who stood in her way. The sport’s gatekeepers would surely have pushed her out at first chance were it not for the inconvenient fact that she could out-skate almost anyone; the first woman to pull off the insanely difficult triple axel, Harding rocketed up the rankings, as judges begrudgingly acknowledged her superiority.

I, Tonya races energetically through Harding’s early years, from her days as a preschool skating prodigy to her gawky adolescence (with Robbie in braces and a frizzy ’do as teenage Tonya). The script, by Hope Floats screenwriter Steven Rogers, identifies a pattern of abuse in the athlete’s life, passed like a baton between two domineering figures: insult-slinging stage mother from hell LaVona (Allison Janney, relishing every line of bilious dialogue) and Harding’s impotently frustrated, small-town-loser of a beau, Jeff (Sebastian Stan, who apparently can act, when not playing the brainwashed sidekick of a super soldier). On paper, it’s grim stuff. But Gillespie, the journeyman who made Lars And The Real Girl and the Fright Night remake, directs I, Tonya like yet another entry in the endless cycle of Goodfellas clones, employing freeze frames, multiple narrators, and enough played-out, wall-to-wall pop cues (yes, “Spirit In The Sky” makes an appearance) to stock a jukebox. As with most Scorsese knockoffs, there’s a pretty obvious and cynical critique buried in the mess of incident—something about the public desiring villains more than heroes. That the film isn’t titled American Skater counts as a kind of restraint.

Without going full Rashomon, I, Tonya adopts a he-said, she-said structure, sitting its characters down for contradictory talking-head confessionals (many of them based on real interviews with the real people), while interrupting some scenes with fourth-wall-breaking asides to the audience. The reliability of the narrative is frequently challenged: While Gillooly denies the accusations of domestic assault that the film strings into uneasily comic montage, Harding pauses while firing a rifle at her husband, insisting the anecdote we’re watching is “bullshit.” Throughout, Tonya attempts to reclaim her public image, mangled by hearsay and talk-show punchlines. The tone gets awfully accusatory, with the athlete bluntly implicating the viewers who gorged themselves on the 24-hour news cycle: “You’re all my attackers.”

The hypocrisy of such sanctimony is that I, Tonya is every bit as hooked on sensationalism as the tabloid vultures who set up shop around Harding’s house. It doesn’t so much re-litigate her case—tried in real court and the one of public opinion—as jazz up the juiciest details: the “motivational” maternal shit-talk that Janney performs like a profane comedy routine; the on-the-ice outbursts, sometimes punctuating Gillespie’s robustly staged skating sequences; and every twist and turn of Gillooly’s hapless criminal conspiracy, which turns the backstretch of the movie into a dimwit caper, dominated by Paul Walter Hauser’s broadly farcical take on Eckhardt and his mouth-breathing delusions of grandeur. Meanwhile, I, Tonya’s slipperiness doesn’t really extend to the open question of what Harding knew or didn’t know about the plot against Kerrigan; the film takes her insistence that she wasn’t in on the scheme basically at face value, because to do otherwise would risk complicating its depiction of her as a victim of bad luck, a worse social circle, and relentless class snobbery.

Still, there’s a poignancy to Harding’s battle against her own bad reputation, and it survives I, Tonya’s flippant, needle-drop approach thanks to the rage and resignation of the lead performance. Dimming one’s mega-watt glow may be a shortcut to acclaim for movie stars, but Robbie’s take on Harding—more of a spiritual embodiment than a mannerism-obsessed impression—never feels like any kind of anti-vanity stunt. Since her breakout role in The Wolf Of Wall Street, filmmakers (and slobbering journalists) have looked at Robbie and often seen nothing but a bombshell to be coveted. I, Tonya may be more of a pop-biographical exercise than a deep interrogation, but there’s a resonance to the synergy between its star and its subject: one famous female artist reclaiming her professional narrative by playing another who never quite could.