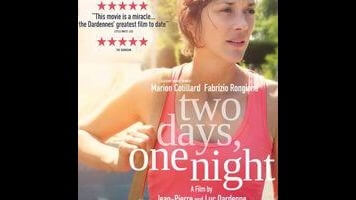

Marion Cotillard is a weekend warrior in the beautiful Two Days, One Night

Two Days, One Night is a small miracle of a movie, a drama so purely humane that it makes most attempts at audience uplift look crass and calculated by comparison. By now, cinephiles have come to expect excellence from the film’s directors, Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, the Belgian sibling team who made Rosetta, The Son, and several other masterful visions of blue-collar desperation. So while it’s no shock that these reliable pros have continued their peerless track record, it is surprising to find them futzing, quite successfully, with their own winning formula. For the first time, the lead role in a Dardenne movie is played not by some talented nonprofessional plucked out of obscurity, but by a bona fide international movie star, Marion Cotillard. Beyond that, and more crucially still, Two Days, One Night offers a respite from the bleakness that sometimes characterizes the brothers’ best work. It’s tough but never dispiriting, chasing glimmers of hope across a rocky economic landscape.

Thankfully, plunking a famous actress down in front of the directors’ pursuing lens never proves distracting, mostly because the star sheds almost all traces of vanity. Occupying what could have been a Gena Rowlands role in a different era, Cotillard plays Sandra, a mother of two who awakes, in the film’s opening scene, to discover that her job at the solar panel factory is on the chopping block. In an especially wormy middle-management move, the company has opted to put her fate in the hands of the other employees, allowing them to save her job at the expense of their annual €1,000 bonus. Predictably, and perhaps understandably, only two of the 16 workers have voted in her favor. Still recovering from a long bout of depression, and dangerously close to having to move her family back into public housing, Sandra teeters on the edge of an emotional collapse. But at the urging of her supportive husband (Fabrizio Rongione), she convinces her boss to allow for a second, anonymous vote on Monday morning. And so with her livelihood at a stake, she spends the weekend tracking down her co-workers, making a direct emotional appeal to each of them in hopes of securing a majority tally.

It’s a brilliant premise. Working with a ticking-clock scenario that’s almost conventionally exciting, the Dardennes essentially reconfigure 12 Angry Men into an episodic drama about the zero-sum game of economic crisis. As Sandra hops around town, from one employee’s home to the next, the film unfolds as a series of miniature moral confrontations, Sandra politely but firmly forcing her co-workers to weigh her predicament against their self interests. What’s remarkable is that the Dardennes never reduce any of these characters to heartless villains; each has his or her good reason to vote for the bonus, the loud-and-clear message being that it’s the company and management that have engineered this lose-lose situation. That makes Two Days, One Night the rare film about our new financial age to resist cynicism; it acknowledges how bad things have gotten all over without giving up on people’s capacity for goodness.

On a more basic level, the Dardennes’ latest is also just a powerful, urgent story of a working-class striver finding her strength in a time of weakness, family and empathetic colleagues helping her steel herself against despair. Cotillard, who may be the most emotionally expressive actress working today, turns Sandra’s door-to-door pilgrimage into a struggle not just for employment, but against the sea of hopelessness that threatens to swallow her whole. Without revealing where the film goes, or how that final tally shakes out, it’s fair to say that the Dardennes find a way to end their most affective feature on a stirring note, but without violating the hard-won realism they’ve cultivated over an entire sterling career. They truly earn that hoariest of recommendations, “feel good.”