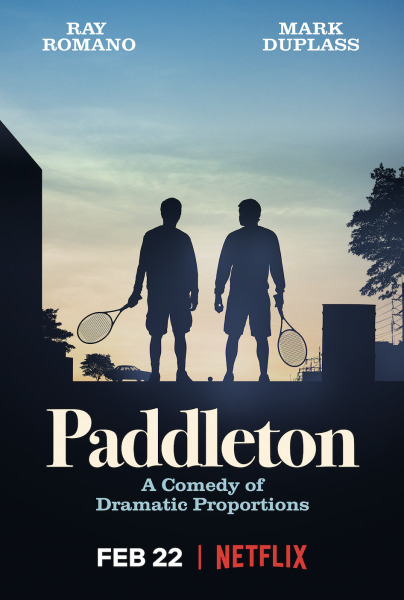

Mark Duplass and Ray Romano share terms of endearment in the moving bromance Paddleton

Opening with a diagnosis of cancer that’s soon revealed to be terminal, Paddleton more or less amounts to an hour and a half of slow-motion assisted suicide. Sound like fun? Remarkably, this low-budget two-hander—arriving on Netflix just a few weeks after its Sundance premiere—manages to generate a fair number of laughs, even as it does full justice to the scenario’s underlying gravity. Written by Alex Lehmann (who also directed) and Mark Duplass (who also plays one of the two lead roles), Paddleton takes its emotional cue from Terms Of Endearment, expanding that film’s final stretch into an entire feature and replacing mother-daughter bonds with the deep but usually unspoken love shared by two male buddies. A bit of cheating is necessary to achieve the stripped-down dynamic that Lehmann and Duplass apparently wanted, but the payoff is an atypically intimate portrait of testosterone-fueled friendship.

As soon as Michael (Duplass) learns that he’s a goner, he resolves to end his life on his own terms, while he’s still reasonably alert and pain-free. He doesn’t want to do it alone, though, and requests the help of upstairs neighbor and best pal Andy (Ray Romano)—which makes sense, since the two are inseparable anyway. Andy has some kind of generic office job, at which he’s seen for about 15 seconds at a time (“Here, Ray, hold this folder and look businesslike”), but when he’s not there, the guys are generally either watching their favorite old kung-fu movie, Death Punch, or playing paddleton, a game they invented that involves bouncing a ball into a big rusty oil drum after first ricocheting it off the back of a defunct drive-in movie screen. (Any symbolism derived from this film’s path straight to Netflix was presumably unintentional.) Andy accompanies Michael on a six-hour road trip to obtain the drugs with which he’ll kill himself, and remains by Michael’s side through the whole process. Being supportive, however, doesn’t necessarily preclude such desperate shenanigans as buying a bright pink kiddie safe at the drugstore, locking the pills inside it, and refusing to tell Michael the combination.

Paddleton isn’t a film that benefits from too much viewer cogitation. It simplifies the process of obtaining a lethal dose of medication, blithely ignoring any legal issues; here, the sole hassle is finding a pharmacy that doesn’t refuse to fulfill such prescriptions on moral grounds. ($3,500 buys 100 pills, and Andy has a point when he asks whether Michael couldn’t have just taken 100 capsules of almost anything.) Also attributable to poetic license, perhaps, is the absence of any other human being in either man’s life. Michael gets (and ignores) a phone call from a sister at one point, but seems to have zero interest in saying goodbye to family. Andy, meanwhile, is not just his best friend but his only friend, and vice versa. Anything that might potentially prove a distraction from this relationship just conveniently doesn’t exist. That’s efficient, certainly, but it also tends to undermine those aspects that seek to be raw and real.

Still, the punches do land. Again, a lot of Paddleton is surprisingly upbeat and funny: Romano does his standard dyspeptic routine, to solid effect, and the characters’ road trip inspires the sort of free-form riffing that Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon invariably do while driving. There are recurring comic bits about an incomplete hangman game (on one of Michael’s T-shirts!) and Andy’s claim to have thought up the greatest halftime motivational speech a coach could ever deliver, both of which land on memorably poignant punchlines. All of this is prelude, though, to the final moments shared by Michael and Andy, which demand—and receive—virtuoso work from both actors. On the whole, Paddleton isn’t quite as strong as was Lehmann’s relatively little-seen debut, Blue Jay (also written by and starring Duplass), but it builds to a duet as harrowing and tender and moving as anyone could desire, or fear, or both.