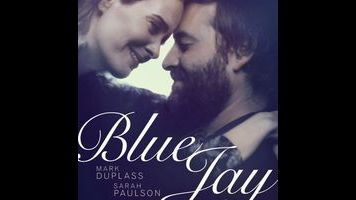

Set in an unspecified small town—sleepy establishing shots suggest a location somewhere on the West Coast—the indie film Blue Jay begins in time-honored fashion, with a chance meeting between a man and a woman. In this case, they’re shopping in the same aisle at the supermarket, and a major silent drama ensues before either party even acknowledges the other’s presence. Jim (Mark Duplass) appears to recognize Amanda (Sarah Paulson), but quickly decides to ignore her, though he doesn’t walk away. Amanda then spots Jim and, following a visible struggle about whether or not to say hello, finally does so. Jim greets her warmly, starts to go in for a hug, senses it might be unwanted, manages to retreat before he’s committed himself irrevocably. Duplass and Paulson counteract the deliberately banal dialogue (Duplass also wrote the screenplay) with superbly anxious body language; Jim and Amanda’s “casual,” “amiable” chitchat is so painfully forced that it’s a wonder nothing ruptures. These two people clearly have a troubled history, and it takes Blue Jay only a few minutes to generate intense curiosity about what it is.

Good thing, too, because that relationship constitutes the entire movie. (The only other speaking role is a one-scene cameo by Clu Gulager, playing the proprietor of a convenience store.) This is a simple story of high school sweethearts who reconnect roughly two decades later, deriving virtually all of its power from the rapport between its two stars, and how precisely they communicate what’s not being addressed. Jim and Amanda’s initial awkwardness gradually metamorphoses into deep affection; they seem so perfect for each other that it’s impossible not to wonder about the cause of their breakup—especially when Amanda, looking through Jim’s childhood room, discovers a sealed envelope with her name written on it. Paulson, who’s often cast as “the sensible one” (see Carol, Martha Marcy May Marlene, Marcia Clark), gets a rare opportunity to show off her more playful side, while Duplass exhibits a raw vulnerability that’s sometimes harrowing to watch. Both are admirably served by first-time director Alex Lehmann’s black-and-white imagery, which suggests a timelessness very much in keeping with this exercise in turning back the clock.

Eventually, Blue Jay has to reveal what happened between Jim and Amanda all those years ago, and it does so in clumsily melodramatic fashion; the film’s last 10 minutes or so are its weakest, unfortunately. Duplass’ script also trades so heavily in nostalgia that it sometimes could be mistaken for an adaptation of an “only ’90s kids will remember” listicle. (The centerpiece is a half-mocking, half-sincere slow dance to Annie Lennox’s “No More I Love You’s.”) At its best, though, this paean to youth’s unfulfilled dreams, as seen from the cusp of middle age, achieves a rueful poignancy. The highlight—overly convenient, perhaps, in terms of strict dramaturgy, but still very effective—observes Jim and Amanda as they listen to a cassette they made when they were teenagers in love, play-acting their distant future as a couple. The thought that they might not end up together never occurred to them back then; the awareness of what actually happened threatens to overwhelm them now. When the tape ends, Jim immediately tries to ease the tension with a joke: “We weren’t very cool.” “No,” Amanda agrees, “we were deeply uncool.” Both yearn to be that uncool again, though. Blue Jay’s acknowledgement of that embarrassing truth hits home.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.