Indeed, the one hint of complexity that emerges in this superficial portrait concerns Felt’s true motivation, which Mark Felt suggests was more about protecting the bureau from an interloper than about exposing a corrupt administration. The film begins shortly before J. Edgar Hoover’s sudden death in May of 1972, introducing Felt as a fiercely loyal underling who orders Hoover’s secret files destroyed the instant he hears the news. Though seemingly the obvious choice to succeed Hoover as director, he’s passed over by Nixon in favor of L. Patrick Gray (Marton Csokas), a former Navy officer whose main qualification for the job seems to be personal loyalty to Nixon. When Watergate breaks, Gray takes steps to curtail the investigation, and Felt starts leaking information to reporters (including Time’s Sandy Smith, played by Bruce Greenwood), primarily to ensure that Gray will be ousted and that the bureau will retain its independence from the executive branch. That Nixon was also forced to resign seems almost incidental.

James Comey’s Senate testimony in June, in which he admitted leaking memos detailing his conversations with President Trump in the hope that doing so would spur the appointment of a special counsel, gives Mark Felt’s ode to patriotic subterfuge a (likely unexpected) shot of contemporary relevance. As history, however, the film is surprisingly wan. Rather than compete with legendary cinematographer Gordon Willis, whose deep shadows made Woodward’s meetings with Deep Throat in an underground parking garage unbearably tense, writer-director Peter Landesman (Parkland, Concussion) largely avoids Woodward and Bernstein altogether, focusing instead on Felt’s comparatively humdrum maneuvering within the bureau. These players—including William Sullivan (Tom Sizemore), Edward Miller (Tony Goldwyn), and Charles Bates (Josh Lucas)—aren’t terribly well known, and Landesman struggles mightily with exposition. “Bill Sullivan and Mark Felt, together again,” Sullivan says to Felt, in a typically clumsy exchange. “Who would have thought it? I think I was the one who recommended you to the old man for your first big promotion.” (Felt’s reply: “You know you were.” And now so do we!) At times, it’s hard to tell whether you’re watching a movie or browsing through an alumni newsletter.

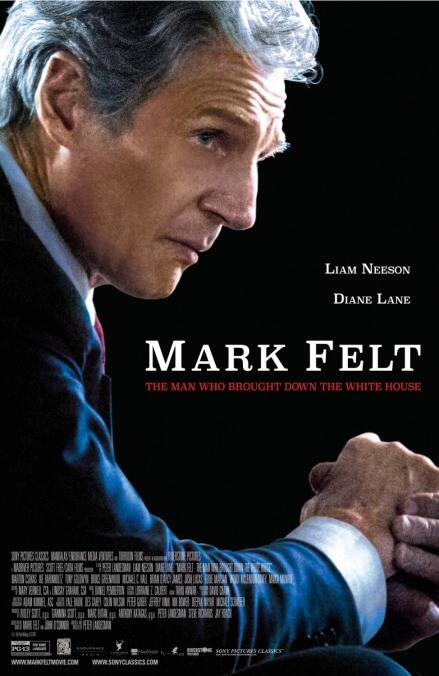

That might not have been fatal had Mark Felt managed to find a compelling angle on Mark Felt, above and beyond his role in Watergate. Neeson looks suitably imposing with a silver head of hair but is given little to play apart from a fundamental sense of decency, which is always tough to make compelling. (Felt’s overzealous pursuit of the Weather Underground, which led to a conviction for civil rights violations, is addressed only in a brief epilogue, but would probably have made for a stronger character study.) Landesman touches on Felt’s home life—his unhappy wife, Audrey (Diane Lane), would later commit suicide, and his rebellious daughter, Joan (Maika Monroe), had cut off contact with her family at the time and gone to live in a commune—but fails to integrate the personal and the professional in a satisfying way, making these scenes feel like pointless subplots rather than facets of a biography. In the end, Halbrook’s brief, wholly invented performance feels just as valid as this full-length profile. The shadows were enough.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.