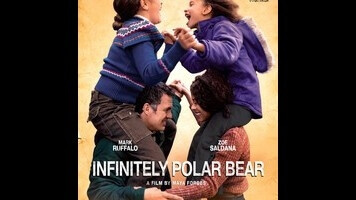

Mark Ruffalo has a gift for believability. He may have a low-key version of movie-star charisma, but in between his scene-stealing appearances as Bruce Banner in the Avengers series he excels at bringing regular-seeming guys to life in movies like Foxcatcher, The Kids Are All Right, and Zodiac, among his many wonderful credits. In Infinitely Polar Bear, Ruffalo attempts to put a recognizable, charismatic, slightly worn face on manic depression. Somehow, though, he comes up with a vaguely theatrical, and vaguely wearying, performance. His Cam Stuart, father to two young girls and semi-estranged husband to frustrated wife Maggie (Zoe Saldana), is supposed to come from money, and to signal the character’s slightly foppish, slightly rakish background, Ruffalo affects his manic episodes with flowery outbursts, chain-smoking, and what sounds, at times, like a fake sketch-comedy voice. Though his rich-guy cadence isn’t especially convincing, he’s better at conveying instability—so good, in fact, that Cam never seems more than marginally functional at parenting, and the movie loses any tension between the character at his best and at his worst.

Ruffalo may be working with difficult biographical details; though it’s not formally credited as such, writer-director Maya Forbes based her film on experiences growing up with a bipolar father. When Maggie pursues a scholarship to Columbia University business school in order to improve her family’s finances (Cam’s relatives provide just enough money to keep them at the poverty line), she leaves Cam, fresh from stays in a mental hospital and halfway house, to care for their daughters Amelia (Imogene Wolodarsky) and Faith (Ashley Aufderheide) in Boston. To show how hard this is on the family, Forbes focuses on the kid actors (especially Wolodarsky, the director’s daughter) making the extra-saddest faces; to show the kids growing up, she gives them the occasional precocious sentences that sound more like the words of an adult screenwriter.

Once Maggie splits for New York, the movie settles into routine: Cam kinda-sorta tries to take care of his daughters, his daughters kinda-sorta try to take care of him, and Maggie comes back for weekend visits, looking on with hope and dismay (mostly dismay—add this to the list of parts that don’t give the talented Saldana enough to do) as Cam fills their apartment with half-finished projects, calling their family “not the kind of people who throw perfectly good things away.” Forbes assembles Infinitely Polar Bear as a series of often-painful family-album moments, and she underlines that approach by throwing in passels of un-arranged details and pseudo-characterization via fake home-video, often scored with generic folk-rock that sounds more 2015 than 1978, when the movie is set.

Polar Bear gestures toward the gender (and racial) politics of its time period when it makes the subtle point that Cam’s stay-at-home-dad status looks, to some people in 1978, more or less indistinguishable from a genuine mental health problem, as does Maggie’s attempt to earn money for her family by studying and working long hours. But not much comes of these observations; the movie’s family feels so insular that all of the other characters are essentially bit parts: extra bodies to walk into the frame and look appalled or discomfited by Cam and his outsize, sometimes oblivious personality.

It can’t be easy, putting family experiences up on screen and shaping them into a compelling narrative. But Infinitely Polar Bear doesn’t make it easy on the audience, either, and not because of its difficult subject matter. The daughters are barely distinguished from each other, Maggie’s arm’s-length affection for Cam doesn’t deepen, and Ruffalo overacts like never before. This isn’t much of a movie. It’s a series of well-intentioned anecdotes.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.