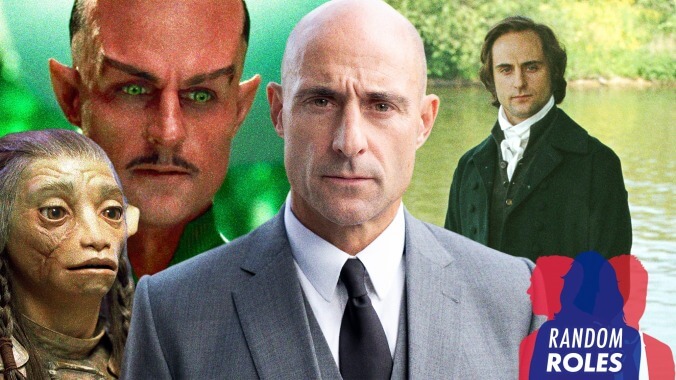

Mark Strong on a life playing spies, villains, and morally compromised doctors

Image: Graphic: Libby McGuire

Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

The actor: A working actor for over 30 years, Mark Strong has made a career out of playing sinister-looking, stoic, and somewhat bad guys. He’s played no fewer than five spies and/or members of the intelligence community, at least three evil foils opposite various and sundry superheroes and/or superbrains like Sherlock Holmes. Like many British actors, he’s also popped up in multiple period pieces, from the BBC’s Emma to a 2006 adaptation of Tristan & Isolde.

His latest gig is as Daniel, a troubled and duplicitous doctor who’s performing illegal surgeries in a cavernous room below a London tube station. As viewers of the series Temple—which was originally broadcast on Sky One in the U.K. but is coming to Spectrum in the U.S. on Oct. 26—will come to understand, Daniel’s motives are mostly pure, but what started as a good idea may have unintended consequences for himself and those around him. The A.V. Club talked with Strong about that role, as well as his longstanding working relationships with Matthew Vaughn, Sam Raimi, and Colin Firth. The full interview is below, as well as some video highlights from our Zoom call with the actor.

Temple (2020)—“Daniel”

The A.V. Club: Temple is an adaptation of a Norwegian show called Valkyrien, and your wife is one of the producers. Is that how you came to the role?

Mark Strong: Yeah, my wife is a very successful producer in her own right. She’s worked at the BBC and Channel Four here in the U.K. She ran Ridley Scott’s company for a time and made movies with him, but then decided that she wanted to kind of go on her own and develop her own production company. And, she’d been doing her work, I’d been doing my work, but the point came where we just where we were just like, “Why don’t we work together?” I felt like I was working with other people and she was choosing other actors. And we thought, “Well, don’t we know we can do this ourselves?”

So we were looking for a project for a long time and happened to be watching the pilot of a Norwegian show that we’d been recommended. We were at home on the sofa watching one night, and she said, “I wonder if someone’s got the rights to this.” I said, “I have no idea.”

A few days later, she had organized the whole thing. We were on a plane to Oslo, and we went to meet the guys who made the original Valkyrien. We asked them if they would let us have the rights, and they liked us. We got on and they said sure. So we we took their project and adapted it and ran with it.

AVC: It’s interesting, too, because the show is about Daniel’s extreme love for his wife, and what he’ll do to keep that love alive.

MS: What I was looking for was a character who’s conflicted. I think that always makes the best drama. Every actor will tell you that if you can find a character has lots of light and shade, they’re always the best. And Daniel is morally and ethically compromised for the whole of the first season. But we thought that the way that you can keep people interested in him without losing sympathy for him—because in a way, you need to be on his side—is to make the bedrock of the reason that he’s doing all of this stuff the fact that he’s trying to save his dying wife. So the whole thing is happening for love.

It’s just that he’s the kind of guy that, in order to leap hurdles, which is which is what surgeons do whenever they come across a problem, doesn’t panic. You just have to deal with one problem and move on to the next problem and deal with that. And that’s essentially what Daniel does during the series.

So we found a character that I really wanted to play that was conflicted and interesting, and my wife found a show that I think she really wanted to make because, at its core, it’s a love story.

AVC: He makes some decisions from the get-go that may not play out how he might ideally want them to because he’s compromised in some way. He’s not thinking incredibly clearly.

MS: I think it’s more the fact that he is an everyman and he is thrown into an extraordinary situation. He’s made the kind of crazy choice to try and keep his wife alive when she has specifically asked him not to do that should the medication that she’s taking not work. He makes that choice because he can’t let her go, and in keeping her alive, he has to keep forming an unholy alliance with a character who has access to space underneath the London Underground in the tube tunnels. The best thing he could think of in the moment is to ask that guy if he could use the space under there. In return, the guy says, “Sure, if you’re prepared to do some off-the-grid surgery for me so we can make some money.” So he gets into this odd couple alliance with this guy. It’s a symbiotic relationship that allows the guy to make a bit of money, but allows Daniel to keep his wife alive.

AVC: You guys are filming season two now. How’s that going?

MS: What was great about the first season was that we had a blueprint, so we took that and adapted it. We didn’t copy it by any means. I think the Scandinavian vibe is very different from the British one, but we took the characters and the idea of this underground surgery and and ran with that.

For the second season, we’re really excited about it because it’s us. We formed a writers room. We got some people together. We now know who the characters were that we developed and we decided to try to take them and give them more stuff to do. So each of those characters that you see in the first season become even more vivid in the second. We’re very excited to be doing it, but I’m really hoping that people will gravitate to the first season and find something that they like which will help them get into the next season.

Kingsman: The Secret Service (2014); Kingsman: The Golden Circle (2017)—“Merlin”

AVC: You have worked with Matthew Vaughn a number of times, including on the Kingsman movies. How did that relationship develop, and why do you think you both keep going back to the well?

MS: I’m really proud of the fact that I tend to work with directors often more than once. I’ve worked with Matthew four times. I think I’ve worked with Guy Ritchie three times. I’ve worked with Ridley Scott a couple of times. All British directors. There is a sort of a certain pride, I think, in the fact that they they trust you enough to ask you back.

Matthew I got to know because basically I had done a TV show over here in the U.K. called The Long Firm in which I played a kind of 1960s gangster. Guy Ritchie had seen it and wanted to put me in one of his movies. And Guy and Matthew were partners. They made Lock, Stock, And Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch and all this stuff together. But Guy decided that he wanted me in his movies. And I think Matthew probably took a look at that and said, “I want him to be in my movies as well” when he started to become a director.

We just got on, you know. I think when you know the dance with the director and when you know each other well, you don’t have to spend a lot of time worrying about what you’re saying, how you’re saying it, whether someone’s going to understand what it is you’re trying to say… It just makes the whole process so much simpler.

AVC: There’s a degree of trust there as well when he comes to you. You know they’re good projects, you know they’re going to be handled well, and so on.

MS: Well, film is all about the director. In theater, of which I’ve done a lot, when it’s time for the first night, the director has to go and sit at the back of the auditorium and fret. They have no control whatsoever. But in film and in television, they are in control of where they’re pointing the camera and then ultimately in the edit of what they choose to use. So you have to trust them. You have to trust that they’re good filmmakers and they know how to make a film because everything that you’re doing is in their hands. So you have to like them. You have to get on with them. I think otherwise it makes the whole filming process a bit of a downer.

1917 (2019)—“Captain Smith”

AVC: Speaking of process, you were in 1917 last year, which was famously shot in long, sweeping takes. What was that like?

MS: Phenomenal experience. Very unusual.

Sam [Mendes] is another one of those directors. I did a couple of plays with Sam when he was running a theatre called Donmar Warehouse in London back in the early 2000s. We did Uncle Vanya and Twelfth Night together, and then we took it over to New York. So I knew him from that time.

He basically called me and said, “Look, I’ve got this part in this film that I’m doing. It’s not a big part, but there’s a bunch of other guys, and they don’t have big parts either. It’s really about these two young boys, but I think you’d really suit the part.” I didn’t hesitate for a second. I’ve always loved working with Sam. He’s such a meticulous director who creates such a lovely atmosphere on set. There’s never any panic. It’s always very well controlled.

I went to go and do 1917 not really knowing what it was going to be like. All I knew was that I had two scenes and those scenes were gonna be played in real time. They were actually, I think, a month apart. One was in Wiltshire in the countryside, and one was up in Glasgow, and it was a one-shot deal. You rehearsed a little sequence and then you carried on rehearsing it until you felt you had it, and then you shot it a few times. There were no close-ups. There was no cutting in. There was no changing lenses. That was it. It’s the quickest, easiest job I think I’ve ever had, but one of which I’m the most proud because I thought that film was extraordinary.

Fever Pitch (1997)—“Steve”

AVC: Speaking of working with people multiple times, you’ve been in several movies with Colin Firth, the first being Fever Pitch. There was a U.S. adaptation of that Nick Hornby novel starring Jimmy Fallon, but the U.K. version hews closer to the original work, and has such a cult following.

MS: First of all, I am an Arsenal supporter, so [the team in the movie] is my team. I grew up in an area of London called Islington, which is where Arsenal were basically based, and they’ve been around since the late 1800s, so it’s a team that’s really linked directly to the community. If you’re born there and grow up there, then you have very little choice but to work out whether or not you’re gonna be into the football or not.

Basically I loved it. I’m not a rabid fan, but I certainly follow that team. When I was asked to come in for an audition, obviously I’d read Fever Pitch. It is really the diary of a football fanatic, but I also knew that Nick Hornby was a fervent Arsenal supporter. I couldn’t believe it. So when I went in, not only did I go in, I let them know that I was an Arsenal fan.

When I went back for a [callback], I took a photograph of myself in my mum’s back garden with me in the football kit doing a throw in with the ball and then discovered that that’s not dissimilar to the cover of the paperback Fever Pitch. It’s a young boy about the age that I was wearing his Arsenal jersey. Anyway, that swung it for me, and I got to do the film. It was like art and life meeting.

That was the first time I think I worked with Colin. We got on really well. It’s ironic: They asked us to go to football matches and take a camera with us. Now, nobody thinks anything of taking a selfie, but we didn’t have mobile phones when that film was made, so we were trying to take a selfie with a little Kodak Instamatic camera. This is in a football ground surrounded by loads of men looking at these two guys with their arms around each other, trying to take a photograph of themselves. It wasn’t easy, but we did get to go to about five or six games for free for research, and that’s the best research that I think I’ve probably ever had to do.

Shazam! (2019)—“Dr. Sivana”

Sherlock Holmes (2009)—“Lord Henry Blackwood”

AVC: You have played a number of antagonists, including in Shazam!, Green Lantern, and Sherlock Holmes. Why do you think people like you as an antagonist and what’s been the most fun one to do?

MS: There is a kind of very honorable roll call, isn’t there, of British actors going over to the States and playing the bad guy, whether it’s Jeremy Irons or Alan Rickman or Anthony Hopkins. There’s a lot of us who go over and get our own try playing the bad guy, and I think there’s a number of reasons for that. Often we haven’t been around as child actors or in the business, so we’re not known. When you first go over and play the villain, you’re probably not as well known as a lot of the American actors are. Also, you have a kind of accent. It sets you up for something different, something other. It can be a Russian accent or whatever, but then you can be the bad guy.

More than that, I genuinely think we have in our history Shakespearean characters like Macbeth and Coriolanus and Richard III who are the bad guys and they’re the leads in their plays. I think American culture reveres the hero, or certainly used to. I remember when Dexter came out, I couldn’t believe it. The lead was a guy who was actually committing murder. Up until that point, it always seemed to me that U.S. shows were always about a good guy who’s always a hero. The Shield was another time when I saw that the main guy was a bad guy. It has started to change a little bit in the States, but certainly when I grew up the shows were always about the hero in the U.S., whereas we Brits weren’t afraid to play the bad guy, and actually the bad guy was often the main part. We’re just in touch with that more. So I think when it comes time to do that on screen, it wasn’t a difficult leap to make.

I think you could often play a villain very obviously evil or bad, and then it’s just a bit boring. But I’ve grown up making them as interesting as I possibly can. So even if they’re not liked, at least they might at least be understood. I hope it’s that.

Anyway, that’s what people respond to with bad guys. Also, I think vicariously, people live their bad guy fantasies through whatever bad guy. We don’t get to do that stuff in everyday life. Ryan Reynolds once said to me on Green Lantern that heroes are basically designed to throw a punch, crack a smile, and kiss the girl. You can probably do that in your real life, but you can’t vanquish whole planets.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)—“Jim Prideaux”

The Imitation Game (2014)—“Stewart Menzies”

Zero Dark Thirty (2012)—“George”

Deep State (2018)—“Max Easton”

AVC: You have also played a number of spies in movies. Do you think that’s also the accent?

MS: Well, first of all, the world of spies has inherent drama. It’s about betrayal and trust and secrecy and possibly murder and all of that kind of stuff. It’s the stuff of drama, really. So it’s not surprising, especially as we don’t really know or understand the world of spying—because I don’t know about you, but I don’t know any spies. If I do, they certainly haven’t told me that they’re spies. So we don’t really know that world well. We’re kind of guessing. I think that makes it exotic.

Also, if you were asked to cast somebody in a particular part or you had a particular part, you have to think of somebody. Chances are you’ll think of somebody who’s done something similar recently. So I had a whole period where the bad guys happened one after the other, largely because I played a bad guy. Everyone said, “That guy is going to get the bad guys.” And then when I played a spy and was good at playing a spy, they said, “He’s really good at spies.” So I honestly think they go in cycles. At the moment, with Daniel, I suppose I’m playing conflicted, morally challenged characters, having been through all the evil guys and the mysterious spy type guys.

Kick-Ass (2010)—“Frank D’Amico”

AVC: If you’re on a run like that, do you have to make a conscious decision and say, “that’s enough spies for now”?

MS: Yeah, you can choose to do that… Oh, this will answer your earlier question, which I didn’t, about which baddie I really loved playing: I really loved playing the incomparable Frank D’amico in Kick-Ass. That was such a wild film, and that part was so unexpected. I really enjoyed playing that guy, even though he’s kind of a scumbag. It was great fun. But somebody did say to me, “You gotta be careful. If you play too many bad guys, you’ll only ever get seen as a bad guy.” I thought, “Well, they’re really interesting characters.” You know, they were great fun to play in.

I played Frank D’Amico in Kick-Ass. I played I think it was Godfrey in Robin Hood, the Russell Crowe one that Ridley [Scott] directed. I played Lord Blackwood in Sherlock Holmes. I think those three movies all happened within the same year. Now I know they’re all bad guys, but they’re three incredibly interesting characters to play. So I never thought of them as bad guys. They were interesting characters, and that first and foremost was the thing to me. So I never worried about getting typecast. I just wanted to keep playing these interesting guys. And then, sure enough, a part came along where I was cast as what everybody thought was the bad guy. But actually, I was a good guy. So it started to work the other way round.

I think for me, it’s always been variety. And if you want a long career, you can just play through a particular type of part for a while and there’ll be another one that comes along.

The Brothers Grimsby (2016)—“Sebastian Graves”

AVC: You’ve even subverted the spy genre with The Brothers Grimsby, where you play a CIA agent. That’s not quite as serious as the other films, though; what was it like to work with Sacha Baron Cohen?

MS: It was insane, as you can probably imagine. He’s like a ballistic missile for comedy. He’s always looking for the gag or the thing that will make people laugh. And he’s very scientific about it and very particular. And actually, when you work with him on set, there’s a hell of a lot of improvising. We’d spend hours and hours and hours improvising. We shot loads and loads of footage that never made it into the movie, and I was surprised at how how specific in particular he was.

I remember one point he had to grab my underpants and pull them up to surprise me and he realized that I was wearing Calvins. I think he went, “Do you think your guy would wear Calvins?” He said when he played Borat, he didn’t wash. He was a bit smelly. You can’t tell that on the film, but he was so deep undercover that it meant he was very, very meticulous about everything that was done in the movie. But I enjoyed that and I thought he was great fun and worked really hard.

AVC: It’s always interesting to hear about such singular performers, because working with them is really a masterclass in whatever their specific talent is.

MS: Yeah. He has very specific ideas about comedy and what works and doesn’t work. There was a sequence, for example, where he was wearing a sort of funny jester’s hat while drinking beer at the same time peeing into a glass or something, and then the beer that he was drinking was going to come out of the jester’s hat. He decided not to use that because he said, “Is this too much going on? A joke has to be clean. If a gag is going to work, it’s has to be cleaner than than that.” So he threw that idea out. But it was interesting watching him work through stuff like that.

AVC: Can you think of other instances or projects where you feel like you’ve learned something that really stands out, or that you’ve taken into other projects you’ve done?

MS: I can’t think of anything specifically, but you certainly do build up a huge reservoir of themes that you’ve done and reactions that you’ve had to things. For example, let’s take something like anger. Often anger is required and you have to work out whether you open to the same level of anger every time and whether you’re going to use your own anger or whether you’re going to use the character’s anger and whether that kind of anger is different from another character. So you build up a different reservoir of reactions and behaviors.

I don’t think that’s particularly specific to for me, but they’re just all in there by osmosis. They’re all rolling around in there. So when I read a scene or I’ve come across a new scene, I tend to just use instinct rather than take or pluck things from the stuff I’ve done in the past.

EastEnders (1989)—“Telephone Engineer”

AVC: Your first TV appearances was on EastEnders. If you went back and watched that, what notes would give yourself? It was a while ago.

MS: I think it was the first thing I ever did on camera, to be honest. Somebody just rediscovered it recently. It wasn’t out there and I’d completely forgotten about it.

I think what I had back then was a fantastic lack of concern for the artifice of filming. I just played it like it was completely real. I probably didn’t even know where the camera was, whereas over the years I built up an understanding of how the camera works and how you can use the camera and how lenses work and how different sized lenses require different kinds of acting and performance size. Whereas back then I was just doing it like a play. I was involved in the theater at the time. I was very natural. I suppose if I look back, I might give myself a bit of advice about how the camera works and where it is and just be aware of that. Craft a performance knowing that.

Emma (1996)—“Mr. Knightley”

AVC: You’ve also done a number of roles—mainly in literary adaptations—that have been put to film a number of times. You were in Oliver Twist, for instance. You were in a TV version of Emma. the same year the Gwyneth Paltrow movie came out. A number of people have played Mr. Knightley. How do you take a role like that and make it your own?

MS: You don’t. I never compare myself to what’s gone before. I don’t watch other people’s performances because you might inadvertently find yourself taking stuff from them.

I’ve never used that kind of research before. I just sort of do my own thing because if a role is well written, it’s all there on the page. You don’t need to find out how it was done before. But, again, I’m used to that because in the theater, you do that all the time. If you play Richard III, hundreds of people will have played it before you.

Sunshine (2007)—“Pinbacker”

AVC: You have been in two different movies called Sunshine. What do you remember about making the Danny Boyle one?

MS: Oh, my God, I remember being in the makeup chair for over eight hours. Getting picked up at 3:00 in the morning, traveling across London, getting in a makeup chair at around 4:00 and then being meticulously painted because I had to look like a burns victim, basically. I played a character, Pinback, who was the captain of the first ship that got up to the sun and he got badly burnt. So basically they’d put that all of that makeup on me until lunchtime. They’d shoot something else in the morning and I would do my scenes in the afternoon. And when everybody was saying goodbye at the end of the day, I’d still have an hour and a half, two hours to get all of this stuff off.

So it took a long time in makeup, but I thought the effect was amazing. I thought it looked incredible. And I really wanted to have a go of playing a part like that because I knew Danny; I’d done a play with him and I’d done a television thing with him. I told him, “I want to be in the movie,” and he said, “I know what you can play.” And I said, “I’d like to play that part.” He was never intending to cast an actor as such to play that, but I wondered if I could transform that much because, again, that’s what I enjoy about acting: If I can effect some kind of transformation. That’s the bit that’s interesting for me.

Green Lantern (2011)—“Sinestro”

John Carter (2012)—“Matai Shang”

AVC: Would you do it again? Or if it was 12 hours of makeup?

MS: I think, again, with the knowledge that I now have as a more experienced actor, I might ask about how long I’d end up being in the makeup chair. But yeah, I probably would do it again because I thought the effect was incredible.

It’s the same with Green Lantern actually, playing Sinestro. My interest in that part was, “Can we really deliver the guy from the comics onto film,” because he looks so extraordinary in the comics. He’s got this big red head, he’s got this widow’s peak of hair, these eyebrows, and a little pencil thin mustache. I was just intrigued as to whether we could really recreate that look on film. And that was about four hours of makeup. But I thought it was really good. It worked out really well.

AVC: Green Lantern wasn’t very well received, and you were in John Carter around the same time, which got a similar reaction. How much does that affect you? Do you read reviews? Do you care?

MS: I totally care. It does affect me because you work so hard on these things and you want them to succeed. Nobody works on a movie in any capacity halfheartedly. You all do it and you want it to be successful. But it is kind of alchemy. There are so many components that go into making a successful movie. You can’t guarantee that they’re all going to work or even if they do work, that they’re all gonna fit together perfectly. So I think that’s why we keep making movies, because we’re chasing that alchemy. And sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t.

I care when it doesn’t work because I feel like all that hard work that everyone has put in is for nothing. But I don’t mind. You just move on. We just keep going.

The Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance (2019)—“Ordon”

AVC: In The Dark Crystal, your work there is even more hands-off than normal—you aren’t necessarily seeing the sets, seeing the cinematography, and so on. You have no say in the final product. What do you like about working on something like that, or doing the other voices you’ve done?

MS: Well, again, I did it because the transformation was really interesting and it was something unusual and different. And also it was directed by the same chap who directed Grimsby. So he was a friend and we’d been in the trenches together doing that movie. When he asked me to come and do it, I didn’t hesitate. I just liked the idea of doing the voice and it being a little gelfling, you know.

Cruella (2021)—“John”

AVC: Cruella is supposed to come out next year. What can you say about that movie and about adapting that beloved character that we’ve all come to hate?

MS: I don’t know how much I am allowed to say about it, actually, because it’s not come out. I did my work on it. I spent most of my time with Emma Thompson and that was an absolute joy. I play John the valet. He’s her butler. She plays a character called the Baroness and has a phenomenal presence on screen and wears the most outrageous, amazing costumes. And I’m her sidekick.

I really enjoyed it because it meant I got to be around and chat with her all the time. And Emma Stone was really incredibly hard-working and really very good. I was really impressed with her and Emma Thompson both and was totally impressed with how hard they worked and how much they know their characters. I really think people are going to enjoy that movie.

AVC: Are you more apt to do a movie if it shoots in London?

MS: I don’t mind, actually. I will travel. I’ve worked all over the world, and that’s part of the joy of being an actor as well. You can find yourself somewhere you never thought you’d ever be and not just on holiday either. You actually live in a place for a while and get to know it a lot better than you would if you were just a tourist. Plus, I’m doing the thing that I love. So I feel very lucky in that respect.