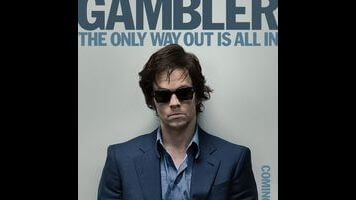

Mark Wahlberg’s remake of The Gambler isn’t really about gambling

“I’m not a gambler,” insists Jim Bennett (Mark Wahlberg), the title character of The Gambler, though both his actions and the name of the film chronicling them beg to differ. English professor by day, wannabe high roller by night, and shiftless, washed-up novelist by both, Jim makes his first appearance at a shady Los Angeles gambling den. Here, in the film’s opening scene, he wins big at the blackjack table, doubles down and loses it all, wins again on money staked to him by a loan shark, and then blows all of that on another foolish bet—all within 10 minutes of running time, and without a second of hesitation. None of that looks like the type of behavior one might expect from a man who doesn’t have a problem. Yet as Jim gets deeper and deeper into trouble, and the details of his charmed life shift into focus, an alternate explanation for such reckless wagering presents itself. Maybe Jim isn’t a gambler. Maybe he’s just a rich asshole with a death wish.

The Gambler draws both its name and its basic plot structure from a 1974 James Toback movie, which itself was a loose adaptation of a Dostoyevsky novel. Both of those works were very plainly about addiction, presenting antiheroes whose compulsive betting was a reflection of their authors’ shared vice. By contrast, this remake, slickly directed by Rupert Wyatt (Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes) and loudly written by William Monahan (The Departed), has refashioned the same story into a swaggering California crime comedy about a golden boy rebelling against his own privilege, mostly by flushing every dollar he can get his hands on down the toilet. Blackjack is more of a noose than a needle for this self-destructive blowhard, and if that sounds less dramatic than the tale of a man who just can’t walk away from the table, it is significantly funnier.

Wahlberg excels at braggadocio, and that, thankfully, is Monahan’s specialty: Early scenes of Jim pacing around his classroom, berating his students for their lack of natural talent, play like little more than blatant showcases for the screenwriter’s colorful shit talk. Monahan structures The Gambler as a series of punchy conversations, counting down the days until Jim has to shell out thousands of dollars to both the stoic kingpin Mister Lee (Alvin Ing) and impatient gangster Neville (Michael Kenneth Williams). As the deadline nears, our hero pulls a couple of star athletes into his dilemma, hits up his wealthy mother (Jessica Lange), and considers borrowing what he owes from Frank (John Goodman), a truly ruthless lender who warns him to find another way. Goodman delivers his spooky-amusing speeches with relish, as though he were auditioning about a decade late for The Departed.

A more serious movie would treat the looming threat of debt collection as a source of mounting suspense. But even as Jim blows every lifeline he receives, The Gambler keeps its cool; it’s the most casual downward spiral in recent memory. There’s a lot of humor in the character’s incorrigible nonchalance: When Neville comes knocking for his money, Jim absently suggests that he stake him more gambling capital, and Williams conveys a disbelief so deep it almost looks like admiration. Less compelling is the quasi-romantic relationship between Jim and his sharpest pupil, played by overqualified Short Term 12 star Brie Larson. While basically the inverse of a certain tiresome archetype—let’s call her the stable brainy dream girl—the character still exists primarily to shove our male hero into a sea change.

For all the pop and flavor of the tough-guy dialogue, neither Monahan nor Wyatt seem especially interested in establishing an authentic atmosphere for their world of underground casinos and credit-line crooks. (One gets the impression that The Gambler is set in Los Angeles, as opposed to Vegas or Atlantic City, for chiefly financial reasons.) But maybe that’s just because, again, this isn’t really a gambling movie. It just uses the high stakes of blackjack and roulette to goose its not-exactly-relatable story of someone who has everything—money, acclaim, charisma, good looks—but still feels like he has nothing to lose. In any case, none of the gambles Jim makes over the course of the movie are as ballsy as the film’s casting strategy. Will audiences really buy Mark Wahlberg as a wordsmith too brilliant for academia? Smart money says no.