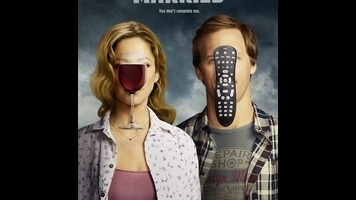

Married: “Thanksgiving”

In Married, creator Andrew Gurland is attempting such a wearily optimistic portrait of married life that the show becomes unclassifiable. A sitcom in form, it regularly delves into its characters’ dissatisfaction with their lives with devastating effectiveness. As a half-hour drama, it often trucks in traditional sitcom physical comedy and farce with unlikely success. Tonally, when it works, Married pulls off the neat trick of blending absurdity and ennui into something like profundity, all in a 21-minute episode of television.

“Thanksgiving” doesn’t work. Kicking off the second season, Married is out of balance. The drama flirts with emotion but glances off. And the comedy barely seems to be there at all. In the show’s best episodes (“The Playdate,” “Halloween”), Russ and Lina Bowman’s comic struggles come from a resigned partnership in absurdity. Nat Faxon and Judy Greer were inspired choices as leads—best known for broader comedy, they convincingly portray a couple who used to be a lot more fun, and whose wry asides and knowing glances say a lot about why they’re still together. When, in the first scene tonight, their teenaged daughter comes to breakfast wearing a crop top, Russ bursts out that she looks like a slut. Lina objects to the word, but then riffs, “Russ! Don’t say ‘slut’ when you really mean ‘escort’—she’s high end.” “You mean the kind that also gets you gym membership?” “Maybe even tuition for night school.” Meanwhile, the poor girl has stormed off, Russ and Lina’s parenting style clearly a familiar way to wake up in the morning. Is that bad parenting? Maybe, but it’s how Russ and Lina get through the day.

So when the Bowmans take a trip to visit her mother Janice (Frances Conroy) and second husband Ed (M.C. Gainey) at their swanky retirement village and discover that Janice’s dementia has become markedly worse, it’s disappointing that their reaction is so ordinary. Conroy (using a hoarse voice alongside her signature brittle cheerfulness to signal Janice’s decline) bustles around preparing a huge Thanksgiving dinner—only it’s not Thanksgiving. Ed counsels everyone to just go with it, as his attempts to correct his wife have only upset her, so the Bowmans settle in for some turkey, only for Lina to discover a bottle of lube in the bathroom. Horrified that Ed is having sex with a woman who often can’t remember who she’s currently married to, she demands that Russ do something about it. The setup promises any number of possible scenarios—from the wacky to the tragic—but “Thanksgiving” really doesn’t commit to any of them.

The division of labor in the Bowman marriage plays out here in its least interesting form, with Russ—the boyish, fun one—making halfhearted attempts to broach the subject to the friendly but imposing Ed, and Lina—the resentfully responsible one—confronting her stubbornly oblivious mother. Faxon and Greer have done outstanding, subtle work both embodying and blurring those roles on Married, but here, Russ is the goofball and Lina’s the scold, which could still work if either were given anything entertaining to do. But apart from some envious goggling at all the amenities afforded the retirement community’s residents and some enervatingly low-key incompetence in the weight room alongside the hearty Ed, Faxon’s easygoing vibe is too bland this time out. (His comical delight at seeing how helpful factotum Dave Silva’s Artillio will uncap a beer for him recalls Homer Simpson discovering the joys of retirement home living in “The Two Mrs. Nahasapeemapetilons,” however.) And while Greer, as ever, brings more to Lina than the “thankless wife” role might suggest, a plot about snap judgments and badgering is more than even her knowing, beleaguered death stare can overcome.

It’s tempting to say that the whole farcical aspect of the “having sex with your dementia-afflicted spouse” plot fizzles, but it’s more accurate to say that “Thanksgiving” isn’t as interested in the comedy here. The closest it comes to going for laughs is in the gym when Russ looks on in horror as Ed, instructing him on proper weight technique, keeps saying things like, “Spread ’em wide! Pound ’em harder!” It’s as if the show shares Russ’ discomfort with the gag, as the scene mercifully and quickly ends there. The casting of Gainey is a canny choice, the veteran character actor’s twinkly smile always carrying, as it does, the possibility of menace (something his bulk next to the birdlike Conroy only reinforces). That Ed turns out to be as benignly loving as he does is a sad, sweet, and welcome surprise. His explanation to Lina, “I love Janice and I would never do anything to hurt her. We still connect, and there’s some days when she forgets my name. But it’s okay—she knows that I love her” making Lina see that, in a long marriage, people are going to have to find painful, complicated ways around their inevitable problems. Gainey and Greer are outstanding here, his simple words and slight sheepishness playing off her grudging acquiescence in a way that communicates their relationship with very little.

The episode’s B-story, too, hints at things it can’t fully deliver, with Jenny Slate’s Jess and Paul Reiser’s Shep trying to get their toddler into a good preschool. That Brett Gelman’s A.J. was a former parent at the school presents them with the dilemma of whether or not to drop A.J.’s name at their interview, since A.J. is a walking roster of inappropriateness. Even though it’s established that A.J. is still sober after his trip to rehab at the end of last season, there’s a lot of history there, and Jess makes the call to pretend they don’t know him. (Apart from his drinking, drug, and sex addiction problems, Jess adds amnesiac blackouts and public defecation to his rap sheet once she admits she’d neglected to mention him to the interviewer. “I forgot where the bathroom was,” responds the hurt A.J., “Amnesia!”)

Again, the setup could have taken this story either into farce or drama, but, instead, it settles into an unsatisfying middle ground, where A.J.’s wounded feelings (he really was a good parent while his kids were at the school) cause him to show up at the school mixer and childishly pretend he doesn’t know Shep and Jess in turn. But nothing much comes of it—A.J. uses his clout as an “all-star donor” to ensure their son gets in—except for little flashes of character work from the always-excellent Gelman and Slate. It’s always frustrating when a sitcom plot hinges on a conflict that could have been prevented by a simple conversation, but when Slate and Gelman have the necessary rapprochement, the actors sell it. Gelman is never better than on Married, where his signature toothy, crazy-eyed persona is grounded in A.J.’s pain, and his line to Jess (“No matter how bad things got, I have always been there for my kid”) reveals the depths underneath A.J.’s often offputting behavior.

Married is a tough balancing act—and a tough sell. The series’ season-two pickup was a welcome but undeniable surprise. That this first episode doesn’t find the right mix is disappointing, but it’s not a cause for panic. This show functioned more like short story chapters than self-contained sitcom episodes last year, a unique structure that was more rewarding when seen as a whole. This is a great, offbeat cast for a sitcom (or whatever Married actually is), and all six actors (sadly, John Hodgman’s Bernie does not appear here) bring much more to the table than expected. Even an off episode demands attention.

Stray observations

- Continuing the theme from last year, there’s also an undercurrent of racial and class commentary going on here, one that doesn’t necessarily show the characters in the best light, but which continues to suggest that Married is fully aware of how privileged a position everyone involved is coming from. When the conscientious Artillio reports Lina’s statement that “My stepfather is raping my shell of a mother” to the retirement community’s welfare agency, Russ and Lina immediately suggest that “a language barrier” is to blame. Coupling that with Lina’s classist dismissal that she should share her problem with “a handyman” (while the helpful, responsible Artillio is standing right there) says a lot too—the main characters on Married are operating from a place of self-absorption born of white privilege. That it keeps coming up isn’t an accident.

- Paul Reiser continues to be Married’s happy surprise. Shep’s resigned wit at the neuroses of his much younger wife and her friends makes him an endearing—and necessary—outsider perspective.

- “He’s three—he’ll love it anywhere they have juice.”

- “What would you do if I became a vegetable?” “I’d become a vegetarian.”