Marsupilami: The Beast is well-illustrated but not worth the “hoobaloo”

Marsupilami is a creation of the Belgian comics master André Franquin. Originating in the classic Franco-Belgian comic Spirou And Fantasio, the character left when Franquin retired from the series, but Marsupilami has outshone it, receiving his own comics and a Disney cartoon. Still, Marsupilami will likely be forever tied to Spirou And Fantasio, particularly for Francophone readers. So it’s not surprising that, after Émile Bravo’s 2008 Spirou, a recontextualization of the narrative set in Belgium under Nazi occupation (the most recent volume of which came out in English in 2020), we now get Marsupilami: The Beast, set in a postwar Belgium still reeling from the effects of the occupation.

As most American comics readers are likely only familiar with the Disney cartoon, the thought of what is essentially a gritty reboot of Marsupilami might be jarring. However, despite a few runs of the series that featured more realistic international politics, it shouldn’t be forgotten that not only does the character of Spirou (and associated characters) originate a few years before World War II, but the early comics often depicted people of color as beastly caricatures. These comics have never been simple and innocent escapist adventures.

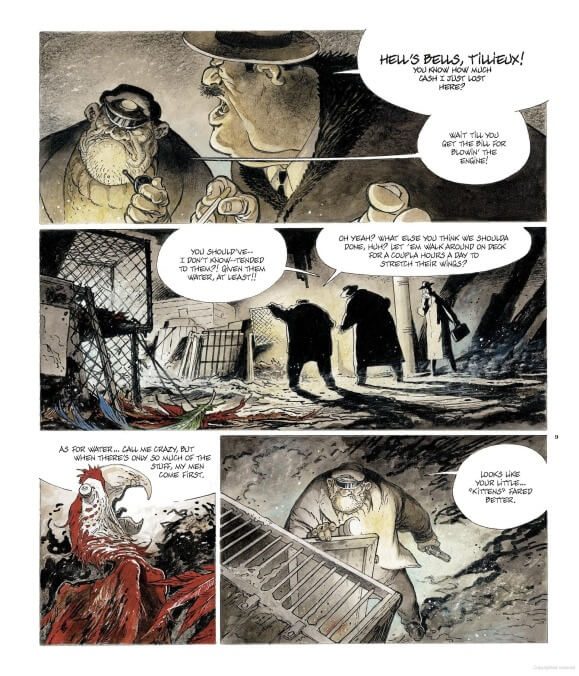

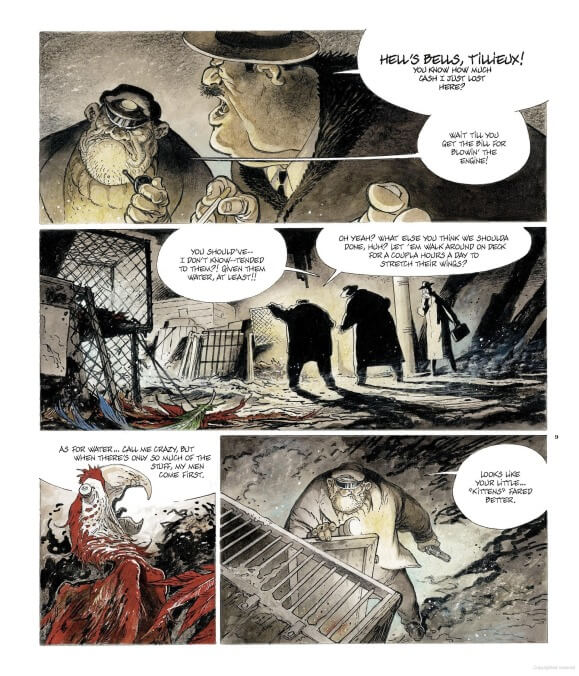

Although Marsupilami: The Beast doesn’t open in a literal jungle, like the 2017 Marsupilami series, it does begin with the steel jungle of a Belgian port, featuring imposing ships instead of trees. The team makes particularly brilliant usage of the Franco-Belgian tradition of large, wide panels. Visually, longtime Marsupilami fans will be delighted to know that The Beast innovates off of the visual style they expect of the character. Although realism replaces the cartoon style of the precedent work, it is a cartoonish realism. While the many animals featured in The Beast would be ill-fitting in the previous titles, they’re still somewhat anthropomorphic, to humorous effect: There’s a drunkard horse who occasionally shares drinks with humans, and in a hilarious and oddly touching decision, bright-red heart emoji surround two beavers madly in love with one another.

It’s this use of coloring, coupled with the sound effects, that wow the most in The Beast. At its heart, the book is a story about a boy who loves animals, and their colors (especially Marsupilami’s) stand out against the sepia of the rest of the art. These same colors pop up in the sound effects, perhaps hinting at how the animals bring color to our protagonist’s life. In presentation and usage, the sound effects are similar to the early comics featuring Marsupilami. (One of few things left unchanged is the fact that Marsupilami still goes “hooba” whenever he’s excited.)

Unfortunately, the book’s visual excellence stands out starkly against its paltry narrative. In 1955 Brussels, Marsupilami’s human companion is a young boy, Francois, the son of a Belgian mother and absentee German father. Our protagonist’s family undergoes bullying and ostracism from other Belgians because of this German connection. The bones of an interesting narrative that could explore the nuances of postwar and post-occupation Belgium are present, but—unlike Bravo’s Spirou—The Beast does not delve deep into its subject matter. For instance, at one point some bullies forcefully shave Francois’ head. This is likely a reference to the punishment for collaboration horizontale (innuendo for women having relations with German soldiers), which was doled out to women across Germany, as depicted in Robert Capa’s The Shaved Woman Of Chartres. In a better book, this might be a powerful moment that captures the story’s themes; but because The Beast doesn’t examine this—not even to discuss whether Francois’ mother underwent something similar—the deeply violent act comes across as just another instance of kids being mean.

Marsupilami: The Beast could have been a fascinating look at the effects of WWII on Europe’s children in the 1950s, but instead it’s simply a well-drawn story featuring Marsupilami—an insouciant but mostly fun read. Perhaps the second volume will match the brilliance of Bravo’s Spirou.