Martin Scorsese finally gets his solemn, powerful Silence off the ground

Silence, Martin Scorsese’s long-in-the-works adaptation of Shūsaku Endō’s same-titled novel about a Jesuit priest searching for his former mentor in shogun-era Japan, is a truly religious piece of filmmaking, in that it looks for meaning in the contradictions and absurdities of faith, instead of its assurances. One might call it a movie of dark ironies or a black comedy without jokes or even the anti-Goodfellas, as the two films complement each other in unexpected ways. Submitting his camera to primeval landscapes, and foregoing his usual Marty’s Favorites playlist in favor of an almost instrument-free ambient soundtrack that qualifies as film music only in a conceptual sense, Scorsese presents a world that is daunting in its mystery, cruelty, and symbolism. As the purest exploration of the director’s great Catholic themes (completely free of New York influences, unlike his earlier The Last Temptation Of Christ), it’s inevitably something of a challenge. It is slow and solemn in stretches and often remote, but it rewards patience with a transcendent epilogue that departs from the main character’s point-of-view to find a glimmer of meaning.

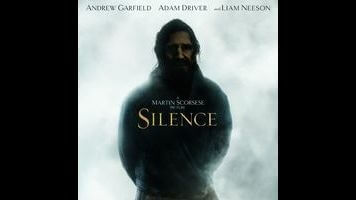

First conceived while the director was in Japan for the filming of Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams (i.e., right between Last Temptation and Goodfellas), Silence is an anti-spectacle, a complete about-face from the lavish period decors and costumes of earlier Scorsese movies like Hugo, Gangs Of New York, and The Age Of Innocence. Filmed in Taiwan, it limits its view of 17th-century Japanese life to far-flung villages, tiny huts, and walled compounds, effectively alternating agoraphobic and claustrophobic perspectives. Its protagonist is the emaciated and unkempt Father Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield). He has come from the Portuguese colony of Macau with his fellow padre Father Garrpe (Adam Driver) to minister to Japan’s persecuted Catholics and to find out what really happened to the head of the last Jesuit mission, Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), who is rumored to have renounced Christianity. The year is 1639, just shortly after the failed uprising of Catholic peasants called the Shimabara Rebellion, and well after Christianity had been officially outlawed as a foreign influence following a brief and unlikely period of popularity and acceptance.

Endō’s novel has been adapted before, as a 1971 Japanese-language film by Masahiro Shinoda. It’s easy to see what attracted Scorsese—who co-wrote the screenplay with Jay Cocks, his collaborator on Gangs Of New York and Age Of Innocence—to the material. It lends itself to a Scorsese film, even if the result seems far removed from the director’s best-known work: pensive, full of fog and figures in tattered clothes. Like so many of his movies, it keeps its narrator-protagonist at about half an arm’s length, but is framed through his wants. Not to put too fine a point on it, but this complex dialogue isn’t an endorsement; it isn’t with Travis Bickle or Henry Hill, and isn’t with Rodrigues. He is a typical Scorsese narrator in that he can’t stop voicing his admiration or disgust for other characters: Garrpe, Ferreira, the crypto-Catholic Kirishtans, and, last but surely not least, Kichijiro (Yôsuke Kubozuka), a coward and serial traitor whom Rodrigues dubs “not worthy of being called evil.” Above all, Rodrigues yearns to imitate Christ.

But in Japan, he becomes a parody of the savior, complete with pieces of silver and a judge all too eager to wash his hands. Rodrigues sees his calling as redemption: to give meaning to the martyred Kirishtans, to refute the rumors that have circulated about Ferreira, and so on and so forth. Scorsese’s signature overhead shots become the eye of God, as felt by this self-absorbed would-be saint whenever he senses purpose; the camera watches from above as he descends the staircase of a Macau cathedral, crosses the East China Sea, or tells the Kirishtan peasants who have taken him in that he must leave for another village. But more often than not, it is constrained by tight quarters or overwhelmed by the scale of landscapes. Scorsese has long taken to using the freely moving Steadicam to suggest swaggering authority—think of the famous Copacabana and “Then there was…” sequences in Goodfellas or any of those long detours across casino floors, count rooms, or bookie joints in Casino. In Silence, he and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto largely avoid powerful camera movements, in keeping with the powerlessness of their central character.

Which is not say that the most rollicking of the great American directors has completely surrendered the aggressive qualities of his style. The opening title card, which cuts short a swell of cicadas, is a doozy, and the film’s use of telephoto lenses to stage shots with multiple characters is overtly reminiscent of Kurosawa. It could even be said that Silence is vaguely about cinema, in that sense that all Martin Scorsese movies are. The Last Temptation Of Christ, his other overtly religious work, subverted the 1950s ancient-times epics that the director has often spoken of being enthralled by as a child; Silence resists the pictorialism and sweep of a conventional historical drama, even as it can’t resist some of the genre’s oldest tropes. (The padres, for instance, all speak with Portuguese accents of varying consistency.) The two faiths, church and cinema, are intertwined; in an unusual bit of casting, Mokichi, the devout leader of an isolated Kirishtan community, is played by Shinya Tsukamoto, the cult filmmaker behind the likes of Tetsuo, The Iron Man and A Snake Of June.

In fact, a lot of the casting in Silence could be seen as suggestive, at least in how it relates viewer expectations to Rodrigues’ futile search for guidance. The film teases and then withholds Neeson’s authoritative presence, and gives the role of the Pilate figure in Rodrigues’ mock-Passion to comedian Issei Ogata. Its treatment of Rodrigues’ spiritual turmoil alternates between mystical affirmation and droll subversion. In its superb coda, the film somehow finds a way to the former through the latter. Having walked and sat alongside Rodrigues as he has wrung his hands in doubt and watched others die horribly while trying to figure out whether it would be worse to betray his faith or their own, Silence delivers a couple of cosmic punchlines, making it one of the few Scorsese films to redeem its protagonist.