Marvel regresses as it tries to move forward with Marvel Legacy

Every two weeks, Big Issues focuses on a newly released comic book of significance. This week, it’s Marvel Legacy #1. Written by Jason Aaron (Southern Bastards, The Mighty Thor) with art by Esad Ribić (Thor: God Of Thunder, Secret Wars), Steve McNiven (Secret Empire, Civil War), colorist Matthew Wilson (The Mighty Thor, Paper Girls), and a variety of guest creators, this one-shot sets up the future of the Marvel Universe by channeling the spirit of the past, for better or worse. This review reveals major plot points.

Another year means another Marvel publishing stunt to grab new readers, but after five years of relaunches, Marvel Legacy comes across as desperate. There are a few new books, but most Marvel titles are sticking around with their old creative teams, with some gaining new Legacy numbering that adds up their previous series’ issue numbers so that Marvel isn’t putting out a new Amazing Spider-Man #1, but a first Amazing Spider-Man #789. The not-quite-relaunch kicked off last week with Marvel Legacy, and it’s hard not to make comparisons between this book and last year’s DC Rebirth when they have such similar formats and roles at their respective publishers. They are both oversized one-shots by popular creative teams setting up line-wide initiatives, and the stories comment on recent criticisms of their publishers and try to counter them with something brighter and more optimistic.

Marvel Legacy is a very competent superhero comic. The idea of a prehistoric group of Avengers in 1,000,000 B.C. is fun, and there are some solid action set pieces, specifically the fight between Ghost Rider and Starbrand. Writer Jason Aaron and artist Esad Ribić blended superhero action with mythological fantasy in their run on Thor: God Of Thunder, and Marvel Legacy has them going for a similarly grandiose tone. Steve McNiven draws a section where the current members of the Avengers Trinity—Captain America, Thor, and Ironheart—team up to stop one of Loki’s latest plots, and there’s a deep lineup of guest artists who contribute single pages checking in with different Marvel characters and setting up their future storylines. Colorist Matthew Wilson shows off the full range of his ability as he adjusts his rendering style and palette for each art team. These are all creators that know how to make a good superhero comic, but there’s a spark missing from Marvel Legacy.

Or you could say there’s a flash massing. DC Rebirth was built around Wally West, who was making his big return to DC Comics after being erased from continuity. He was the point-of-view character, and his personal experience formed the emotional backbone of the book. A single character narrates Marvel Legacy, but her identity isn’t revealed until the final page. Valeria Richards, super-genius daughter of Mister Fantastic and Invisible Woman has been telling readers about all her anxieties surrounding the idea of legacy, and also somehow catching them up on events in a universe that she isn’t currently inhabiting. The narration is intentionally vague so that readers don’t guess the big reveal, but that prevents Aaron from bringing any deeper character to it.

The narration is nondescript omniscient first-person, and rereading the issue with the knowledge that Valeria is narrating just makes that lack of personality all the more obvious. The narration comes across as Jason Aaron channeling a message directly from Marvel editorial, which is then thrown into the mouth of a character with a direct connection to a property readers are desperate to see again. Marvel is teasing the return of the Fantastic Four, but you can only string readers along for so long before they start turning away from you.

Marvel’s treatment of the Fantastic Four is especially frustrating after Secret Wars thrust those characters into the spotlight with an event series that accomplished what Marvel is trying to do with Legacy. Secret Wars pulled inspiration from all aspects of Marvel history to create its Battleworld, providing an opportunity to appease those fans who wish their comics were more like ’70s,’80s, ’90s, etc. by carving out sections of the Marvel Universe that still remained in those eras. Battleworld was never going to last forever, but there are lessons to be learned there in shifting away from one overarching continuity to let popular properties exist in different iterations at the same time. Instead, Marvel is trying to work those old versions back into its current status quo, and it’s going back to the usual bag of tricks. Another giant celestial being threatens the end of the universe. The Infinity Gems are back, and so is Wolverine. There are new changes to the timeline, because that hasn’t been done over and over and over again.

DC Rebirth was similarly fixated on bringing elements of the past back into the current DC continuity, but it at least ended with reveals that guaranteed strong reactions. Batman discovering the smiley-face button from Watchmen, the reveal that Doctor Manhattan stole time from the DC Universe—these are moments that will get people talking because there has been such a passionate response to DC returning to the Watchmen well. Some fans love it, some fans hate it, but no matter how you feel about the ethics, those moments fit for the kind of story Geoff Johns was telling about the positive elements of superhero comics overcoming the darkness that has been thrust upon them in a post-Watchmen world.

Marvel Legacy is also trying to recapture a past spirit of superheroes, but it’s doing that by aggressively marketing to older fans that were introduced to the publisher in the ’70s and ’80s. In a short essay in the back of Marvel Legacy, Marvel editor-in-chief Axel Alonso talks about the inspiration behind the initiative, and it’s telling that he generalizes his childhood experience to that of every comic-book fan. He writes about a comic grabbing his attention from the spinner rack at the five-and-dime, and his grandmother paying 20 cents to buy it for him. This is the way many older comic-book readers were exposed to the medium, but those discovery stories are going to be considerably different for people who first found comics online or at school or by reading graphic novels at bookstores and libraries. The spinner racks at my local grocery store and 7-Eleven disappeared just as I was getting into comics, and I definitely wasn’t paying 20 cents.

Alonso’s story tells us exactly who Marvel is targeting with Legacy: middle-aged fans who long for the thrill of being a kid discovering these superheroes for the first time. But they will never have that thrill again. These are the fans that have a deep familiarity with these heroes, and even with an exciting new direction for a character, that rapturous moment of discovery isn’t going to magically reoccur because Captain America has a new team and old numbering. If there was any doubt that Marvel Legacy was geared toward fans who started reading in the ’70s, part of the initiative involves the return of Marvel Value Stamps, “collectible trading stamps” that are printed on an insert in the first Legacy issue of each series.

If this is Marvel’s way of making readers feel like they’re getting more for their $3.99-$4.99 comic book, it is a severely misguided strategy. It’s a decision entirely driven by nostalgia, but comics don’t cost what they did in the ’70s. Especially at Marvel, where every book is at least $3.99, including the biweekly titles. DC Rebirth was $2.99 for 80 pages, and most of the Rebirth comics were $2.99 for that first year. After almost a year and a half, there still haven’t been any Rebirth cancellations, and DC has given these books significant time to build up an audience in trades if the single-issue sales disappoint.

On the flipside, Marvel Legacy is $5.99 for 64 pages, all the series start at a $3.99 price point, and Marvel has a tendency to quickly cancel books that don’t perform well with their first issues. DC has re-embraced the miniseries format, and Marvel would be wise to follow suit. When nearly every book is an ongoing series and there are 53 of them, there’s no room for miniseries. But when great series like Nighthawk and Nick Fury end after six issues, readers get angry because Marvel didn’t give these books an opportunity to build up an audience. Even though miniseries have a reputation for being sales flops, they might not suffer as much if they weren’t competing with a plethora of ongoings that are only going to last six issues anyway.

Many of these lower-selling titles spotlight women and people of color both on and off the page, and Legacy is arriving in the midst of ongoing debates about the value of diversity in comics. A retailer-only Marvel panel got heated at New York Comic Con yesterday when a retailer objected to Iceman being gay and Thor being a woman, mentioning that he loses potential new readers when they come in looking for the characters they see on screen and find different versions of the characters in the current ongoing comics. There are hundreds of old comics that retailers can recommend to fans who want to see Tony Stark or Steve Rogers or a male Thor, and superhero comics shouldn’t try to cater to people who refuse to engage with a company because it has women and people of color in roles previously occupied by white men. That’s not going to help superhero comics reach new readers, and it actively alienates demographics that could be extremely lucrative.

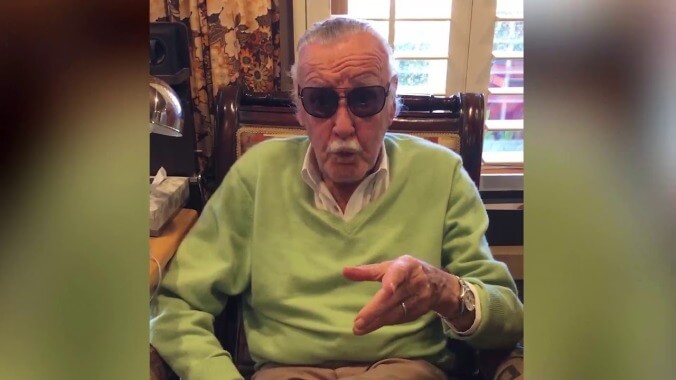

Yesterday, Marvel released a video of Stan Lee talking about how the publisher is a reflection of a world around it and that Marvel stories will always have room for everyone, regardless of race, gender, or religion. It’s a nice sentiment, but the absence of sexual orientation in his list of discriminating factors is strongly felt. It may not be an intentional act of LGBTQ erasure, but it does leave out a significant portion of the people who directly suffer because of intolerance. And while Stan Lee has cultural significance as a Marvel figurehead, he’s not actually setting editorial policies.

The creative team of Marvel Legacy gives you an idea of how inclusive Marvel is behind the scenes. One writer, 13 pencillers, two inkers, one colorist, one letterer. All male, and nearly all white. A grand total of three women worked on this book, with Rachel Dodson and Amy Reeder on variant covers and Alanna Smith serving as assistant editor. It’s hard for Marvel to be a reflection of the world outside its pages when it still entrusts most of its books to white male creators, and that doesn’t seem likely to change as it regresses back to an era that was even less inclusive.