Maybe ignore our grade and see Valerie And Her Week Of Wonders for yourself

Comedy is notoriously subjective: You either find something funny or you don’t, and it isn’t always easy to articulate why or why not. Likewise, horror: It’s scary or not scary, largely determined by personal fears and phobias. Perhaps the most subjective “genre” of all, though (scare quotes because it’s really a style, not a genre), is surrealism. By their very nature, surrealistic or phantasmagorical films offer little to those who fail to connect with a specific, bizarre juxtaposition of images and ideas, aimed directly at the viewer’s central nervous system. There’s not much in the way of a middle ground when it comes to such works—one is either delighted and transfixed or bored to tears. Take a look at the reviews for any film by the likes of Alejandro Jodorowsky, Matthew Barney, or György Pálfi, to name a few extremely divisive figures.

Or just take a look at the grade that’s been assigned here for the 1970 Czech cult movie Valerie And Her Week Of Wonders, released by Criterion this week. Clearly, “bored to tears” is the operative phrase. More than usual, though, that grade should be looked at suspiciously—considered as one small part of an overall critical reaction dating back (in this case) to not long after the writer in question was born. As a general rule, older movies that get covered here at The A.V. Club are well worth seeing, no matter how negative the review may be; Valerie, in particular, is the sort of film that you really have to experience for yourself.

That’s not to say that it can’t be described. Based on a 1945 novel by Vítezslav Nezval (to which it’s reportedly quite faithful), Valerie And Her Week Of Wonders introduces the title character (Jaroslava Schallerová), a girl of about 13, as she sleeps, scantily clad in a gazebo. A man climbs onto the roof, then leans down to steal her earrings, which will serve as one of the film’s many symbolic totems. Running to retrieve them, Valerie encounters a hideous man in a weasel mask, kicking off a series of odd encounters that unfold in a continual dreamlike state, enhanced by Lubos Fiser’s ethereal score. Valerie lives with her grandmother (Helena Anýzová)—the fate of her parents gets revealed as the film goes along—and seems unfazed when Grandma suddenly disappears, to be replaced by a much younger woman (also Anýzová) who claims to be her aunt. Vampires play a part in this substitution, and Valerie spends her time avoiding fangs; flirting with Eaglet (Petr Kopriva), the young man who stole and then returned her earrings; fighting off a depraved priest (Jan Klusák); and just generally being right on the cusp of womanhood at all times.

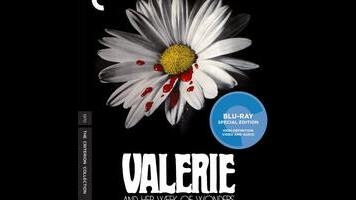

That last aspect can get a bit creepy. In Nezval’s novel, Valerie is 17; by making her four years younger, director Jaromil Jeres turns the film adaptation into a hallucinatory portrait of pubescence, in which Valerie seems less like a girl than like a blank repository for the adult characters’ pervy fantasies. (The film isn’t explicit—a tryst between Valerie and an older woman, for example, is entirely implied—but Schallerová does get naked, for a camera that all but leers, and it’s as discomfiting as 12-year-old Brooke Shields’ nude scenes in Pretty Baby.) To the extent that Jires’ Valerie has a perspective, it’s a decidedly adult one, looking at Valerie from the outside. Even the film’s most Freudian symbolism—blood dripping on a daisy, for example, when Valerie gets her period for the first time (an image that Criterion chose to use as cover art)—is more about how she’s perceived by others than about how she herself feels. It’s as if the natural and supernatural world are jointly celebrating, in a pagan way, her transition into an object of lust.

Still, what matters most is whether one finds Valerie’s seemingly random episodes of lyrical grotesquerie mesmerizing or enervating. According to the Criterion edition’s accompanying essay, written by New York Review Of Books senior editor Jana Prikryl, the parts of the novel that Jires cut were primarily those that helped clarify the narrative. As a result, the movie’s vampires and animal masks and masochistic rituals often feel like weirdness for its own sake, divorced from any context that would make them compelling as more than superficial cult fodder. (Of the three early Jires shorts included in the disc’s special features, two—“Footprints,” and “The Hall Of Lost Footsteps”—are similarly haphazard.) Combine that with an emphasis on a 13-year-old girl’s budding sexuality, minus any effort to explore said girl’s psyche, and some will see not so much a week of wonders as a week of wanking. Others will be entranced. You? There’s only one way to find out.