McConaughey goes commando and other revelations from the new Dazed And Confused oral history

Dazed And Confused is a chatty film, from a writer-director—Richard Linklater—more attuned than most to the cinematic qualities of conversation. Although it was based on Linklater’s hometown of Huntsville and “played” by the state capital, Austin, we never learn the name of the small Texas town where the Lee High School classes of 1977 and ’80 reside. But by the end of Dazed And Confused’s 100 minutes, we’ve been made privy to their participation in and opinions of their school’s sadistic initiation rituals, Abraham Lincoln’s intrusion on their sex dreams, and, in the storyline that provides the collected hangouts with a whiff of narrative, varsity quarterback Randall “Pink” Floyd’s (Jason London) objections to a mandatory “pledge” to abstain from the type of hijinks the film otherwise occupies itself with depicting. The movie distinguishes itself by letting the kids hold forth, regardless of whether they’re saying something legitimately profound about their hopes and dreams or just spilling the latest stoned thought that popped into their heads.

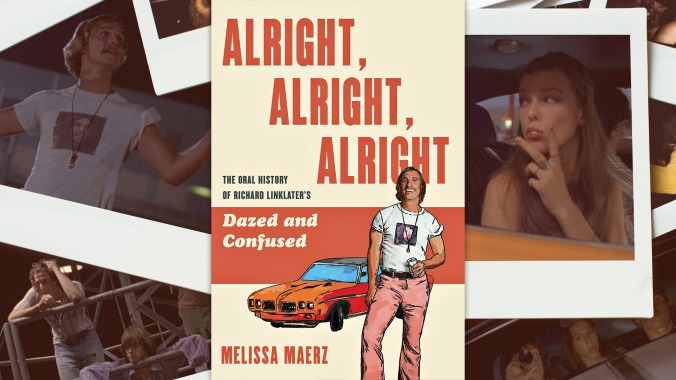

It’d be the type of film that lends itself naturally to the oral history treatment, even if Dazed And Confused hadn’t eventually overcome the meager release foisted upon it by an apathetic Universal Studios to earn its reputation as one of the best high school movies ever made—one that helped lay the groundwork for the careers of Matthew McConaughey, Ben Affleck, Parker Posey, and others. Such retrospectives have appeared in the pages of Maxim and Texas Monthly (about as good an encapsulation of the film’s clashing yet complementary, crude but sophisticated sensibilities as any), but they pale in comparison to what veteran entertainment journalist Melissa Maerz has accomplished with Alright, Alright, Alright: An Oral History Of Richard Linklater’s Dazed And Confused: more than 400 pages of reflection and commentary from not only the people who made the movie, but also the classmates who helped inspire it, the filmmakers and writers who were inspired by it, and the roommates who were there when their uncannily charming buddy schmoozed his way into playing Dazed And Confused’s breakout townie.

Rounded out by excerpts from the script, contemporary newspaper reports and reviews, and the often fiery correspondence from an up-and-coming director trying to preserve his vision (sometimes to his own detriment), Alright, Alright, Alright is well worth reading in toto. But for those with a Slater-like attention span, or anyone seeking out the juiciest backstage anecdotes, here’s a handful of highlights that stuck out during this Dazed And Confused superfan’s reading.

Matthew McConaughey offers a correction in the most Matthew McConaughey way possible

No piece of Dazed And Confused lore is as well-known as the story of how future Oscar winner, University of Texas instructor, and cryptic luxury automobile pitchman Matthew McConaughey landed the part of lech with a heart of gold Wooderson. The production was struggling to fill a few remaining roles; casting director Don Phillips—who’d previously built Fast Times At Ridgemont High’s once-in-a-lifetime ensemble—eventually found his man at the top-floor bar of the Austin Hyatt Regency. It’s a great story, and a testament to the fact that, for all the crucial creative considerations that go into making a classic like Dazed And Confused, sometimes it all comes down to dumb fuckin’ luck.

In Alright, Alright, Alright, Maerz adds to Phillips’ and McConaughey’s recollection of their chance encounter with the point of view from the other side of the bar: The actor’s friend Sam Lawrence was pouring drinks at the Hyatt that night, and he summoned McConaughey after Phillips mentioned he was in town casting “this generation’s Fast Times At Ridgemont High.” In Lawrence’s telling, there was some reluctance on the part of the man who would be L-I-V-I-N’, and you can practically hear the reason he gives in that signature, sleepy drawl: “Nope, I’m stoned, I’m in my underwear.” But on the very next line (the book is edited for maximum comedic punch), McConaughey disputes that account, though maybe not for the reason you’re anticipating: “I’ve never worn underwear,” he says.

Rushmore Academy meets Lee High

Dazed And Confused has long had a reputation as a filmmaker’s film, especially among the directors of the American independent movement who either swam alongside Linklater or in his wake—Quentin Tarantino, for example, has frequently cited Dazed as a personal favorite. Steven Soderbergh and Kevin Smith are both quoted in Alright, Alright, Alright; Jay Duplass says that seeing Linklater bumming around the UT student union post-Slacker made him realize that anybody could make a movie. Wes Anderson and Owen Wilson were living in Austin at the time, too, and Anderson tells Maerz that the duo—who would’ve made their black-and-white Bottle Rocket short around the same time—made their way onto the Dazed And Confused set one day. “I didn’t meet Rick until more years had passed, but he has always been there ahead of us, leading the way for us to follow.”

“Prickford!” “Wood-a-been!”

McConaughey’s good timing helped get him in the movie, but it was somebody else’s bad behavior that expanded his role within it. Plenty of the scenes Wooderson eventually steals were initially intended for Pickford (Shawn Andrews), the floppy-haired, rich-kid stoner whose house party plans are upset by an inconveniently early keg delivery. Given Andrews’ disreputable place in Dazed history, his absence from Alright, Alright, Alright isn’t surprising. What is surprising is the extent to which his co-stars are willing to throw him under the bus on the record. “If all the people in this book are all saying the same thing about him? That’s fucking karma,” says Rory Cochrane—who plays the stringy-haired stoner, Slater—at the end of a chapter that collects stories about Andrews blithely walking through shots with a blaring boombox, improvising his way out of scenes, and pulling focus from his castmates by tossing a rubber ball across a classroom. Linklater is a little more diplomatic, diagnosing the friction as the result of a young, ambitious actor caring too much, while also admitting that when things with Andrews came to a head, he took him aside and told him Pickford was no longer riding off into the sunset with Pink to pick up the Aerosmith tickets—Wooderson was.

“Watch your step, junior”

The setting for the film’s big party scene was a practical concern: One of the 165-foot moonlight towers that still dot the Austin landscape was merely a plausible stand-in for the type of illumination that would be required to capture a nighttime rager on film. But when Slater looks out over the town and wonders how many of the people below are “just goin’ at it,” Cochrane is nowhere near that high off the ground. Dazed And Confused’s moon tower was specially built for the film, and it gave the director a bit of a shock when he first saw it. “[W]hen it finally showed up,” Linklater says in Alright, Alright, Alright, “it was truly the Stonehenge moment from Spinal Tap. It was just a little bitty column!” It’s a movie magic combination of lenses and camera positioning that creates the impression that the kids are climbing into the sky. “You never see it head to toe,” Linklater points out.

Hints of the sadder, longer Dazed And Confused are still there, if you know where to look

If there’s a tension at the heart of Alright, Alright, Alright, it’s that it’s a mostly rosy, largely celebratory look back at a film that cautions against rosy, celebratory looks back. When the book’s winding down, and you can practically hear “Tuesday’s Gone” drifting in on the breeze, unit publicist Jason Davids Scott hits the nail on the head: “I don’t think of it as being nostalgic for the ’70s. I think of it as being nostalgic for the ’90s.” Still, it’s hard not to watch these characters enacting teenage rites of passage and not feel some pang for lost youth, but that feeling tends to subside whenever a freshman has his ass paddled or her face blasted with a high-pressure car wash nozzle. Dazed And Confused lets those feelings and those memories sit side by side, and that’s part of what makes it such a special movie.

Somewhere between the end of principal photography and the film’s release, there was a version of Dazed And Confused that made the melancholy undercurrents more apparent. In Alright, Alright, Alright, editors Sandra Adair and Don Howard describe the pressures they felt from the producers and the studio to trim what was once a more contemplative, three-and-a-half-hour movie into something “faster, funnier, stupider.” Two such cuts involved the home life of freshman Sabrina (Christin Hinojosa-Kirschenbaum): If you’ve ever wondered why she never goes into the house she’s dropped off at at the beginning and end of the movie, it’s because it’s not her house. As originally scripted, Sabrina doesn’t want her classmates to see the smaller home off the street where she and her mom actually live, a bit of class-conscious anxiety Linklater drew from his own adolescence. He tells Maerz the first of those scenes was shot while his mother visited the set; the fact that he stopped himself short of articulating what the character was going through could’ve been an early indication that it wasn’t going to make the final cut.

Rock ’n’ roll, hoochie koo

Alright, Alright, Alright makes it abundantly clear that no great film can claim a single author, and that even the most distinct directorial vision must bend to compromise now and then. But the one fight Linklater refused to back down on involved the film’s soundtrack, the period pop hits that ground Dazed And Confused’s version of May 1976 and give voice to emotions the kids aren’t quite equipped to grasp. In order to cover the cost of big-ticket items like Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion” and Bob Dylan’s “Hurricane”—estimated at $100,000 and $80,000, respectively—the production was depending on a six-figure advance from Universal subsidiary Geffen Records, a deal that fell through when Linklater refused to include a cover by Geffen artist Jackyl. (A memo on the subject—headed “RE: public embarrassment & professional stupidity”—is perhaps the most concrete parallel Alright, Alright, Alright draws between the director and his onscreen avatar, reluctant QB Pink.) The studio let the soundtrack rights go for a song (to prodigal Universal son Irving Azoff, no less), and so although Dazed And Confused CDs sold better than Dazed And Confused tickets in 1993, it didn’t contribute to any of the Dazed crew’s bottom line. The whole experience sat so poorly with Linklater that he says the gold record he got after the album sold its 100,000th copy used to hang in his office bathroom.