Meat Loaf pens an emotional remembrance of his long, complicated relationship with Jim Steinman

There are many topics that we would firmly suggest you not turn to singer and actor Meat Loaf as an authority on: Things one may or may not do for love. Whether two out of three is bad. (It’s a failing grade in the majority of schools!) Politics. (For the love of god, please do not turn to Meat Loaf as an authority on politics.) But one topic that it’s extremely hard to fault the man’s expertise on is being creative partners with Jim Steinman, with whom he crafted 1977's massively, ridiculously successful Bat Out Of Hell (and it’s less-successful, but still pretty damn successful, 1993 follow-up), and in whom Meat Loaf found the perfect partner for his own desires to slam rock ‘n’ roll and Broadway showtunes into one improbably perfect blend of horniness, motorcycles, and pure dorkitude.

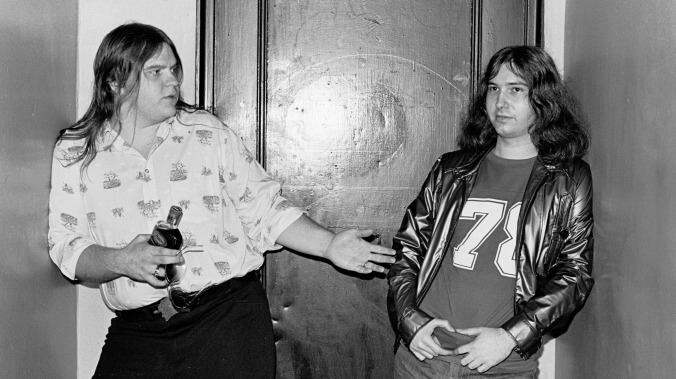

Steinman died earlier this week, after a long series of health problems. Yesterday, Rolling Stone published the results of a two-day interview with Meat Loaf about their partnership, presented in the form of a first-person account crafted by writer Andy Greene. Emotional—“We belonged heart and soul to each other”—melodramatic— “I don’t want to die, but I may die this year because of Jim”—and undeniably just a tad self-serving (the singer asserts that, while “our managers sued each other…my heart never sued Jim. And I know Jim’s heart never sued me”), it’s a fascinating look at the relationship that produced one of rock’s most improbable best-sellers.

The piece tracks the first meetings between the two men (it started, apparently, with a fat joke), before moving into the long period where Bat Out Of Hell was gestating, and Meat Loaf was apparently besieged with offers demanding that he drop Steinman, all of which he refused. “They wanted me to go with [Ted] Nugent and REO Speedwagon, all these people. I went, ‘Stop it! This is not happening! I’m not leaving Jim!’ They go, ‘Then you’ll never make a record.’” They did, but success apparently proved difficult: “Jim wanted the world to know, ‘Hey, I helped create this.’”

If nothing else, it’s a fascinating look at Meat Loaf’s conception of the relationship, which fractured and fixed itself multiple times over the course of the two men’s careers. And it’s hard to deny his central thesis of their long-time creative collaboration: “You have to become a Jim Steinman song. You have to be the song. You don’t sing the song. You are the song.”