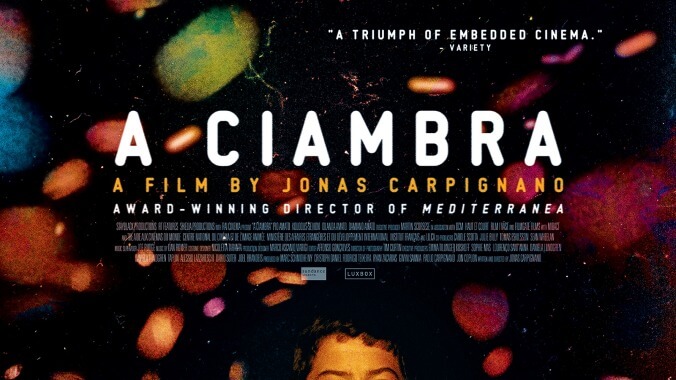

Mediterranea gets an inferior follow-up in the neo-realist coming-of-age story A Ciambra

A Ciambra, a coming-of-age story set in the homely outskirts of the Italian port of Gioia Tauro, is a sequel of sorts to writer-director Jonas Carpignano’s Mediterranea; it isn’t necessary to have seen the earlier film, but it helps one appreciate how much better this follow-up could have been. Last seen as a memorable minor character in Carpignano’s debut, which depicted the lives of African migrants in southern Italy, the illiterate Romani teenager Pio (Pio Amato) has grown up in a family of car thieves, burglars, and assorted other small-time hustlers who resent both the ethnic Calabrians who control local organized crime and the marocchinos who live in tents and shanties farther outside town. Working in handheld 16mm (de rigueur for exercises in latter-day post-neo-realism), Carpignano bobs and weaves through Pio’s family life and criminal enterprises with ease, though one wishes he’d linger more on the latter. But his hand gets heavy and leaden with an awkward plot that finds his young hero trying to prove himself as a man, forced like soft material through a machine of socioeconomic ironies.

Beginning in the same overlap of hard-knocks realism and The Little Rascals as The Florida Project, A Ciambra introduces the children of the Amato clan (played by its teen star’s real-life family members) as chain-smoking cons-in-training. Pio, the eldest of the kids, yearns for the respect of his grown-up older brother (Damiano Amato), but can’t work up the guts to talk to a girl, let alone accompany the men on “business.” But after several members of the family are arrested by the Carabinieri in roundup, the boy decides that it’s his time to show his worth, with the Burkinabe immigrant Ayiva (Koudous Seihon, a winning presence who reprises his role from Mediterranea) as his unlikely mentor.

Caprignano has a strong grasp of the plastics of modern neo-realist style. (Much of the crew—including cinematographer Tim Curtin, editor Affonso Gonçalves, and composer Dan Romer—worked on Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts Of The Southern Wild, on which Caprignano was an assistant director.) His camerawork refuses to treat locations like sets, sneaking out windows alongside Pio. But though the young Italian-American director has an undeniable talent for using non-professional actors, he can’t seem to squeeze his otherwise nimble camera inside his protagonist’s heads; it’s observational, not existential. Mediterranea’s internal tensions wrote themselves: It was the story of the underclass of today’s Europe, antagonized by their surroundings. But in A Ciambra, which unfolds entirely from Pio’s limited point of view, he cheats with contrived conflicts and hokey dream sequences that prove, if nothing else, that regardless of who they are or where they live, characters in art films will always dream of horses and fire.

The result is busy, murky, and remote. It doesn’t have the leftie political clarity of Ken Loach, the purposeful intensity of the Dardenne brothers, or even the character development of Ramin Bahrani’s early features. The past 70 years have produced no shortage of good and interesting films inspired by the socially conscious tough-luck realism of gritty post-war Italian cinema. Despite its naturalistic setting and cast, A Ciambra turns out to be strictly run-of-the-mill.