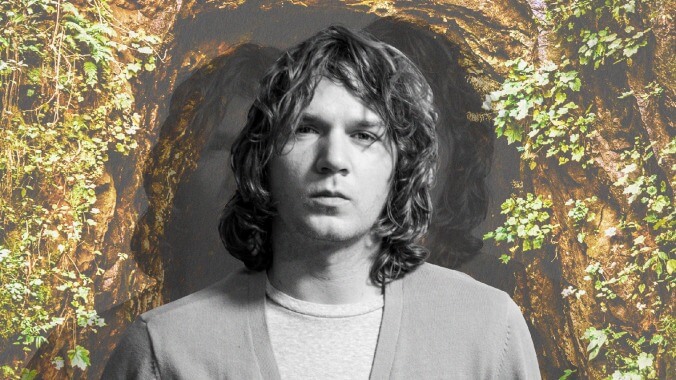

Meet Ian Noe, the Kentucky troubadour who’s gone from the oilfields to opening for John Prine

Image: Photo: Kyler ClarkGraphic: Allison Corr

Ian Noe and I are hunched over bowls of chili at Honky Tonk BBQ next door to Chicago’s Thalia Hall, where he’ll open for Son Volt in a couple hours’ time. Yesterday was beautiful outside, but last night brought a sudden, last-gasp winter storm, and now snow is speeding past the restaurant’s windows while frost creeps across the windshields of cars parked outside.

“This is really good chili,” Noe pronounces, his Eastern Kentucky drawl adding a sense of authority to the verdict.

He’s also right, and it’s surprising. Not the grade of chili, but the fact Ian Noe said anything unbidden at all.

At 29, Noe only left Kentucky for the first time two years ago to go on his first tour, but he’s already grown into somewhat of a folktale within the folk music scene. This might be in part because he generally reserves most of his words for his lyrics. To be honest, he’s a difficult interview. Not in the sense of being a diva, or arriving to the table junked-out like some of the characters in his songs. But he’s so intensely quiet that it renders most of his responses nearly monosyllabic. It’s rare to hear more than a sentence or two at a time out of the songwriter’s mouth unless he’s onstage. Ironically, that’s usually when everyone else in the room shuts the hell up.

About a year and a half ago Noe opened for Colter Wall at the Hi-Tone in Memphis, where he stunned the entire room into silence with staggering songs of pain, love, and wandering, stories at once timeless and wholly a product of this era. He closed with an apocalyptic ballad entitled “The Last Stampede,” which would later cause a member of an otherwise nonverbal post-show smokers’ circle outside the bar to shake his head and mutter to me, “I mean, fuck.”

It was a mutual sentiment. So much so that I found myself driving over 11 hours for the chance to meet him in Pineville, Kentucky, less than two months later. There, his manager, Mary Sparr, introduced us as if teaching a child how to interact with other people.

“Ian, say hello,” she encouraged as we shook hands in the public library’s staff lounge, converted into a makeshift greenroom for Wall—the only other artist Sparr manages—who was set to perform alongside John Moreland in a neighboring theater later that evening.

The next day found everyone snowed in at a mountain lodge outside of town (a story for another time), where I tried coaxing Noe to talk, with some help from Sparr in her room at the lodge. He paced back and forth the entire discussion, alternating between smoking cigarettes through the cracked front door and brewing pot after pot of coffee while recounting his life in Appalachia.

Born in Beattyville, Kentucky (population: 1,200 or so), Noe grew up in the house his parents still occupy. His father, a youth social worker, started teaching his 5-year-old son guitar after Noe saw a video of Chuck Berry playing “Johnny B. Goode.” His mother has worked in the same factory for more than 20 years.

After high school, Noe briefly relocated to Louisville in hopes of starting a band, but a post-Great Recession landscape of low-paying office temp jobs soon forced him back home where a friend got him a gig pulling 12-hour shifts in the oilfields. Even while mostly confined to the rigs, his music began generating talk in the local scene thanks to a handful of bedroom recordings.

For as universal a sound as Noe conjures with his songs, there isn’t anyone quite like him in the current music landscape.

“When he was in the oilfields—I had heard about him, but I didn’t know his name,” Sparr says from the hotel room couch.

For three years Noe worked on the rigs, right up until Sparr got a hold of the songs through a mutual acquaintance. Self-described as “obsessed” with the music, Sparr reached out to Noe, soon convincing him to relocate into the guest room of her Bowling Green home. It was an insurance policy more than anything else, after he recounted a recent near-miss while in the field.

“He almost lost a fucking hand!” says Sparr with a morbid laugh.

Noe lets a smile slide.

“As over-dramatic as that sounds, there were close calls all the time… My boss’s dad, he burned up alive.” He takes a sip of coffee. “But I wasn’t there for that,” he adds, almost an afterthought.

“I was like, ‘I will give you money out of my own pocket not to go back,’” says Sparr.

A lot has happened in the year and a half since we left that Kentucky mountain. Noe released an EP, Off This Mountaintop, while touring cross-country and throughout Europe, seeing a world he might not have ever experienced had he remained on the oil rigs. He’s played for his hero, John Prine, at a recent tribute show, which subsequently landed him an opening spot for the legend on a string of upcoming dates overseas. He’s gained attention from industry giants like producer Dave Cobb, who all but demanded to record Noe’s first full-length album, Between The Country, due out May 31. Literal giants have also taken note: Earlier this spring produced a surreal viral video of Noe arm in arm with Khal Drogo, of all people.

“This is my new friend,” purrs Jason Momoa to the camera for an episode of “On The Roam,” his long-running vagabond vlog series. He and Noe are seated in the movie star’s very swank Vancouver condo after a performance. Momoa’s arm looks about the same width as an anaconda, and Ian’s face gives the impression he might be more comfortable if it were an actual snake draped around his neck.

“Where are you from, originally?” Momoa asks.

Noe struggles to maintain eye contact, shifting between camera, Aquaman, and the ground.

“Eastern Kentucky,” he answers.

Momoa’s bro posse bursts into laughs and claps off-camera, a mix of geographic embarrassment along with perhaps a lingering tinge of disbelief that some Americans actually still possess that kind of muddy Appalachian drawl. It’s suddenly easier to see how someone like Noe might become a man of few words.

Noe, for what it’s worth, seems to shrug off such encounters, along with the notion of representing a part of America so often ridiculed and, perhaps worse, pitied.

“About 10 years ago, I used to get more for my accent. Nobody really says anything now. I don’t feel any pressure because it’s just what I always wrote about it, anyways. It’s a natural thing.”

Between The Country, then, is the understandable conclusion to this first chapter of Noe’s career—an album about Kentucky, its inhabitants, and the seemingly impossible dream of leaving it all behind. For a long time, Noe appeared on the same path as some of his own songs’ characters, destined to tread water as best they could with no clear path to solid ground.

“I did romanticize [leaving]. It took me years to understand the New York I was thinking about wasn’t the New York that was, like,” he pauses for a spoon of chili during our Chicago interview, perhaps realizing he’s managed multiple sentences back to back, “the ’60s.”

Not that he was disappointed by what he recently saw.

“I loved it,” he adds, while still acknowledging missing the “comfort and the quiet” of back home.

Between The Country’s songs are often minor re-workings of what Noe says are actual events from around Beattyville and the (marginally) larger Lee County, along with a couple ideas unashamedly adapted from episodes of favorite shows like True Detective and Justified. Which, given the amount of addiction, death, and loss in his home state, is as understandable as it is troubling. Songs like the tough-to-stomach “Methhead” are culled from the modern-day American plague burning through towns just like Beattyville.

Lyrically, it’s a stark departure from most of his other work, detailing the grotesqueries of addiction so minutely that it verges on body horror. It’s also, in contrast to much of the album, brutally cold toward its title subject, written from the perspective of someone who can’t escape rural life, much less its strung-out inhabitants, and loathes the whole lot of it.

“It’s not ‘sugar-sugar,’” Noe summarizes with a now-predictable succinctness. “When I hear from people back home, [dealers] are just pumping it out. It was a little window [of remission] there for a little while… I mean, it never really left.”

Until recently, Noe’s generally played shows alone, or at most with an accompanying guitarist to fill out the sound. What audiences saw onstage is essentially what they’d have seen while he was off the clock on the oilfields. The emotional depth of his lyrics coupled with his forceful vocal cadence atop delicate melodies are certainly enough to carry his songs on their own, so it would follow that Noe’s first album might mirror his verbal sparsity with an equally bare-bones production approach.

It’s somewhat surprising, then, to hear Between The Country and realize it’s a deceptively lush album. There’s a purpose to each musical layer—the quiet brushstrokes across snare drums and cymbals keeping soft time, background harmonies from fellow singer-songwriter Savannah Conley that smooth out Noe’s general intensity, field recordings of oncoming freight trains and Kentucky stream water—they all aid in depicting the stories Noe wants to tell us, rendering his emotional memories and experiences of Kentucky into audio.

For as universal a sound as Noe conjures with his songs, there isn’t anyone quite like him in the current music landscape. That said, it’s quite possible he’ll face an uphill battle in shaking the skeptics, particularly those who hang on his noticeably familiar, nasal tenor, or predictably question Noe’s “authenticity,” however one might define that shibboleth today.

“Nothing you can do about that. It’s just the way it is,” he concedes, silencing a call from “Pawpaw” on his iPhone. He holds up the device. “We’re all walking around with these, right?”

To be fair, modern technological connectivity might be the largest factor aiding Noe’s unlikely Appalachian exodus. Through it he’s quickly established himself a cult following as priest at the altar of artists like Dylan, Prine, Neil Young, and the Guthries. But seeing him perform, watching audiences literally stop mid-conversation to watch a Kentuckian they’ve never heard of begin to play—it’s easy to envision him ascending to that same pantheon with enough time.

Time, as it so happens, might be the largest thread connecting the songs on Between The Country. Time cut short—by addiction, disease, violence—and time spent dreaming of being elsewhere, loved, clean. It’s best summarized by the album’s title track (Noe’s favorite off the album), with verses recounting real-life tragedies from back home, and a chorus painting one of his grandparents’ frequent aphorisms with a tinge of morbid irony: “On down between the country / Where deer lay ’long the road / On down between the country / Where a long life is a blessed one, I’m told.”

Noe’s now on a musical trajectory that holds as much promise as it does uncertainty. On an even larger scale, we’ve arguably never lived during a time where our country’s landscape provided such a literal and existential threat to its inhabitants, especially those coming from “the country” itself. Most of the time Noe’s hope to “leave these shadows behind for a new peace of mind / If today doesn’t do me in” is enough; other days it’s lines like “through all sorrow / God will follow / But you ain’t seen nothin’ yet”—from the aforementioned knock-you-on-your-ass but currently unrecorded “The Last Stampede”—which feel far more apt. Either way, Noe has more to say than he might initially let on in person, and when he does open his mouth, it’s a good idea to pause whatever you’re doing and listen.