Case in point: the disorientingly violent scene that introduces Galveston’s two main characters to each other. Having just received an apparently terminal diagnosis (though he doesn’t wait around for the details, or to have the necessary biopsy performed), New Orleans mob enforcer Roy Cady (Ben Foster) isn’t thinking straight, and doesn’t ask questions when his boss (Beau Bridges) sends him out to intimidate someone but instructs him not to bring any weapons along. Sure enough, the job turns out to be an ambush: Roy’s partner is summarily executed, and Roy himself escapes only via a desperate lunge and chaotic shootout. Laurent orchestrates this tense, wordless sequence as the nightmarish adrenaline rush that Roy must feel (right down to the loud ringing in his ears from the initial, close-quarters gunshot), casually revealing, once all the bodies have fallen, the presence of a terrified young woman tied to a chair.

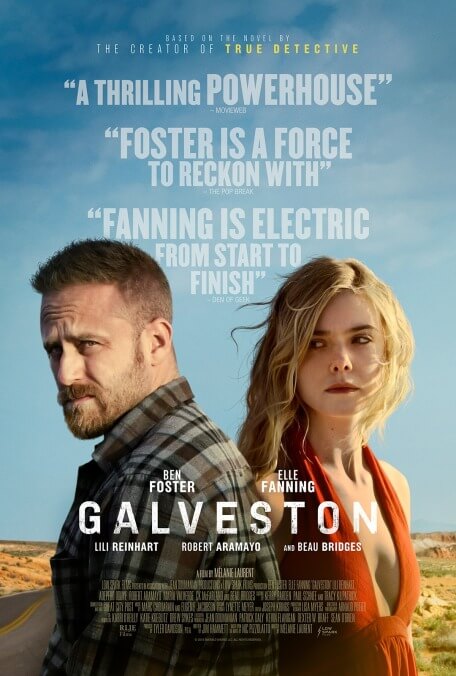

So begins the odyssey of Roy and Raquel (Elle Fanning), who calls herself Rocky. Naïve enough to have believed she’d been hired by a legitimate enterprise (“It was in the phone book! Perfect Choice Escorts, it was like a real business, in the phone book”), Rocky hasn’t even had time to come to terms with being a sex worker. Now she’s on the run with a stranger, being hunted by the mob. Telling Roy that she needs to stop in Orange, Texas to collect a debt, she instead returns to the car with a 3-year-old girl, Tiffany (played by twins Tinsley and Anniston Price), who she claims is her younger sister, though Rocky’s tender solicitude suggests an even stronger genetic bond. The trio then holes up at a cheap motel in Galveston, where Roy, who’s experiencing horrific coughing fits and expects to drop dead at any moment, must decide how much responsibility he wants to shoulder for these two innocent girls.

Reviews of Pizzolatto’s book suggest that its heart resides in this lengthy, relatively plotless middle stretch, which expands the dramatis personae to include numerous other residents and employees of the Emerald Shores motel. (“In this novel,” Dennis Lehane wrote in The New York Times, “it takes a deeply screwed-up village to raise a child.”) The movie, by contrast, loses focus once it arrives in Galveston, barely sketching those supporting characters (though C.K. McFarland makes a strong impression as Nancy, the no-nonsense motel manager) and leaning heavily on impressionistic montages at the beach and pool to suggest a fleeting idyll. Little Tiffany, in particular, seems like an afterthought for a long while, even though the film is ostensibly building to a poignant 20-years-later epilogue (the film is set primarily in 1988) that sees her show up as an adult, played by Riverdale’s Lili Reinhart. Laurent and Hammett instead choose to emphasize the story’s murder and mayhem, which are more cinematic but ultimately less consequential.

Those expecting True Detective’s philosophical (or pretentious, according to taste) dialogue will be disappointed (or relieved)—this is a comparatively terse exercise, more pragmatic than pithy. Foster gives another of his almost psychotically intense, closed-off performances, and the reluctant surrogate-father role he takes on here bounces intriguingly off of his work as an actual, unconventional father in Leave No Trace, which came out earlier this year. Fanning, for her part, continues to tap raw emotion—terror, joy, anguish—with a credible ferocity that makes virtually every other actor her age look timid. Everything about Galveston is expertly realized, provided you’re willing to ignore the nagging emptiness where its emotional core was meant to be. Laurent makes a heroic effort to fill that hole in the film’s final seconds, rapidly juxtaposing sunny, hopeful flashbacks with what’s presumably Hurricane Ike, which made landfall in Galveston on September 13, 2008. It’s not quite enough, but it’s further evidence of a career that may one day inspire the trivia question “What major film director initially became famous in a Tarantino film?”

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.