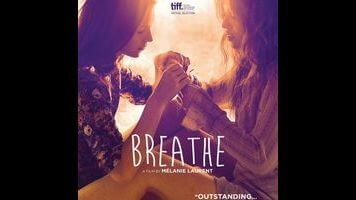

Mélanie Laurent’s Breathe is a thrilling, insightful portrait of toxic friendship

Codependent relationships get explored in movies now and then, but almost always within the context of either a bad romance or a dysfunctional family. Breathe, the second feature directed by French actress Mélanie Laurent (best known for playing the vengeful Shoshanna in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds), tackles the subject from a refreshingly novel angle, depicting a platonic friendship that quickly grows toxic. What generally happens in this situation is that one party constantly oscillates between affection and contempt, while the other becomes addicted to the whiplash effect; a feedback loop takes hold, and things spiral out of control. Breathe—which Laurent adapted, with Julien Lambroschini, from Anne-Sophie Brasme’s novel Respire (also the film’s original French title)—makes every step in that ruinous cycle seem both plausible and disturbing, and it somehow manages to do so without unnecessarily demonizing anyone in the process.

Still, the movie does have an explicit identification figure: Charlie (Joséphine Japy), a teenage girl who’s first seen struggling to be invisible while her parents (Isabelle Carré and Sasha Bukvic) fight over breakfast. Charlie has a best friend, Victoire (Roxane Duran), with whom she’s been tight since grade school, but she nonetheless finds herself immediately intrigued by new transfer student Sarah (Lou De Laâge), a playfully rebellious charisma machine who treats Charlie like her long-lost sister. A few early hiccups seem like simple misunderstandings—Sarah feels understandably hurt, for example, when Charlie introduces her to someone as a classmate rather than as a friend. When Charlie confronts Sarah, in the mildest way, about some apparent lies in Sarah’s personal biography, however, a full-scale war suddenly breaks out, punctuated with cease-fires that briefly make it seem as everything has worked itself out. It hasn’t.

It’s perhaps no surprise that Laurent, who could probably have played Sarah herself a decade ago, gets superb performances from her two young leads. Her formal control is nearly as strong—so much so that what appears to be a rookie mistake at one crucial point (abruptly abandoning the film’s well-established point of view for what looks like a clumsy exposition dump) is ultimately revealed, at the end of a long tracking shot, to be a devastating coup de cinéma. What’s more, the film’s jagged rhythm beautifully mirrors the stop-start frustrations of its central relationship, which is never allowed to become reductive. Sarah’s bad behavior has its roots in a troubled home life (and De Laâge, a potential star, locates subtle shadings in a role that could easily have become a stock villain), while ostensible heroine Charlie is selfish enough that she abandons her longtime bestie Victoire the moment Sarah shows up. Only the very last scene (taken straight from the book) feels a touch overdetermined, in the sense of being predictably inevitable. Even there, Laurent stages the denouement so expertly that the belated appearance of the film’s title card, following a sudden cut to black, feels like an instruction to the audience.