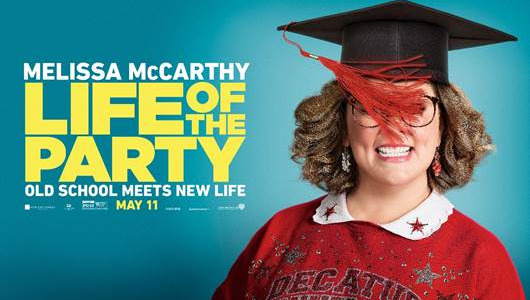

Melissa McCarthy goes back to school in the feeble campus comedy Life Of The Party

Melissa McCarthy may have the elements of an immediately recognizable comic persona, but her years as a character actor have left an impression; many of her movies address, explicitly or not, the mutability of identity. At their best, this produces something like Spy, wherein McCarthy’s character morphs from a caricature of how her superiors see her (an undercover disguised as a frumpy, cat-owning grandma type) to an idealized version of her best self (a sleek, ass-kicking CIA operative). Less successfully, it produces a movie like Tammy, where her shtick changes incoherently from scene to scene, and none of the characters’ ages make any sense.

Life Of The Party, McCarthy’s third film with her husband Ben Falcone (as with Tammy and The Boss, she stars, he directs, and they write together), seems like an easy identity-transformation story. As chirpy mother and housewife Deanna Miles, McCarthy begins the movie in chunky glasses, no-fuss perma-curled hair, and a variety of sparkly mom sweaters, but after her husband, Dan (Matt Walsh), demands a divorce, she decides to return to school and finish her college degree—at the same university where her daughter Maddie (Molly Gordon) is entering her senior year.

It’s a concept high enough to pass muster in an ’80s campus comedy, something the movie winks at with the obligatory ’80s-themed frat party. But McCarthy and Falcone go light on the overbearing-parent shtick, acknowledging Maddie’s initial discomfort and deciding not to make Deanna oblivious to it. When Deanna does get a more traditionally flattering makeover, it’s tenderly supervised by her daughter, who generally appreciates her mom’s attention, even if she blanches at some of her newfound frankness about post-divorce rebound sex. The movie portrays Deanna’s rediscovery of a pre-mom life, and how she squares that freedom with her identity as a loving mother, with a lot of warmth, and its refusal to gin up tired conflicts or mawkish lessons is admirable.

That does, however, leave Life Of The Party without much comic momentum. Deanna resumes work on her archeology degree (though the movie only shows a single course), Maddie’s sorority sisters adopt her as a sort of unofficial den mother, and the movie pleasantly ambles through the school year in search of set pieces. When it finds them, Falcone doesn’t seem to know how to build to a fever pitch. A scene of Deanna tanking an oral presentation is funny—McCarthy remains, as ever, a pro at slapstick—but it escalates too slowly and gingerly to really kill. The scene at the ’80s party is delightful, but it doesn’t build to much, and the movie already has a lot of party scenes.

What it doesn’t have is much insight into college life. The open hostility Deanna faces from a couple of mean girls would be cartoonish in a high school comedy, and someone behind the scenes must have been excited to ink a deal for a Christina Aguilera cameo, because the movie bends space and time to access a college campus where 18-to-22-year-olds worship and revere a pop star whose biggest hits came out when they were somewhere between birth and preschool. (Maybe they all watched Burlesque at sleepovers). It’s sweet that Life Of The Party opts out of “kids today” satire, but surely there was room for some gentle ribbing. Matters get worse off campus: An early scene with Deanna’s parents, played by no less than Jacki Weaver and Stephen Root, is so rambling and sloppy that it only calls attention to how superfluous those characters are; as nice as it is to see these actors, they don’t get any laughs, and their plot utility is almost nil. Most heartbreaking, scenes paring McCarthy with Maya Rudolph (playing Deanna’s best friend) flail with yelling and improv noodling.

The Rudolph character isn’t really necessary either. She’s just part of McCarthy and Falcone’s inviting, Paul Feig-like ensemble generosity. But as in Tammy and The Boss, the supporting characters don’t really feel lived-in, even when they’re played by fine actors giving funny performances. Life, for example, supplies a comic reason for Gillian Jacobs to play a sorority-girl classmate of both mother and daughter: Her character has entered college following an eight-year coma, and Jacobs brings an amusing oddball nonchalance to the part. (“I don’t date fans,” she says dismissing a Twitter follower hitting on her in real life). But this strange character, combined with the sorta-goth played by SNL’s Heidi Gardner, the other superfluous cast members, the generally slapdash ’80s-campus vibe, and the Christina Aguilera genuflection, makes the whole movie feel weirdly out of time. If Feig’s projects with McCarthy dress her up in different genre conventions, Falcone’s often feel more like uneven play-acting. Here, McCarthy commits to a character while the rest of the movie tries on silly disguises.