Meryl Streep hits the right notes as terrible opera singer Florence Foster Jenkins

Every generation likes to think that they discovered the concept of appreciating things ironically. But the truth is, bemused hipsters have been laughing at comically inept entertainment since before Tommy Wiseau was born in whatever Eastern European country he actually comes from. A great example is Florence Foster Jenkins, the New York socialite who, after her career as a piano prodigy was cut short by a hand injury in her early 20s, decided that she would become an opera singer, even though she was objectively terrible at it. At first she performed only at private concerts stacked with her wealthy friends, but news of her “talent” eventually spread. And in 1944, a 76-year-old Florence performed for a sold-out crowd at Carnegie Hall.

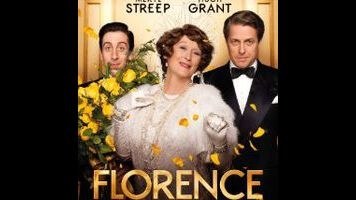

Now Meryl Streep—who actually is a talented singer—is starring as Florence in a film by Stephen Frears. Promotional materials bill Florence Foster Jenkins as a tale of triumph, but that isn’t exactly correct. It’s more of a love story. Throughout most of the film, Florence is depicted as a childlike innocent, sheltered from the harsh truth about not only her talent, but pretty much everything else by her (common law) husband, aristocratic English actor St. Clair Bayfield (Hugh Grant). Bayfield protects Florence not only from jeering audience members (by carefully screening ticket buyers) and bad reviews (by paying off critics), but also from pointed objects, her own hair loss, and the fact that not everyone likes the same foods she does. In return, she puts him up in his own apartment and turns a blind eye to his affairs with other women, most recently a bohemian actress named Kathleen (Rebecca Ferguson).

Much of the film is devoted to Bayfield’s struggle to maintain this unusual state of affairs, and his eventual embrace of Florence as his one true love. This raises some interesting thematic questions: Do sex and love have to go hand in hand? Is a relationship with an allowance any different than one between financial equals? Will what you don’t know really not hurt you? As the film goes on, we learn more about Florence, including that she’s in poor health due to late-stage syphilis given to her by her ex-husband (which is also why she and Bayfield don’t sleep together), and that, under her flighty exterior, she’s a kind and giving person who truly loves music. But these character traits are presented to make Florence into a tragic figure rather than the comic one she at first appeared to be, and not to give her any real depth of personality. Bayfield’s struggle is interesting, and moving. But in a film called Florence Foster Jenkins, starring Meryl Streep as Florence Foster Jenkins, it seems like a missed opportunity to not explore the inner life of Florence Foster Jenkins. It’s not like Streep wouldn’t be up for the task.

She’s certainly up for the challenge of replicating Florence’s utterly unique singing voice. As a singer, Jenkins could hit the notes in the difficult arias she chose to tackle; what she couldn’t do is stay in tune, or in the right rhythm. Streep is typically outstanding as Florence, expressing both humor and pathos wearing Florence’s frumpy costumes and swanning around as if she were the star of the Metropolitan Opera. (And, in her possibly syphilis-softened mind, she was.) On stage, she’s very funny. But off stage Streep plays Florence as a sensitive soul, her eyes welling up with tears every time she hears a particularly beautiful song or off-handed insensitive comment.

Hugh Grant’s face is perpetually locked in a concerned grimace as Bayfield, whose mind always seems to be elsewhere when he’s not doting on his wife. But—aside from Streep, of course—the real scene-stealer is The Big Bang Theory’s Simon Helberg, a talented pianist in real life, as Florence’s accompanist Cosme McMoon. Like Bayfield, McMoon is a nervous type, albeit in a different, more flamboyant (it’s heavily implied McMoon is gay) sort of way. The scene where McMoon comes to accompany Florence at her voice lesson for the first time is honestly hilarious, Helberg’s eyebrows arched to the ceiling and his mouth slightly agape as Streep leans over a chair, clutching her stomach like a woman in labor trying to hit an elusive high note. Impressively, all of the music in the film was done live—that’s really Streep yowling away, and really Helberg trying to compensate for it on piano.

As one might expect from a prestige project like this one, the production value on Florence Foster Jenkins is quite high, and the costumes and set dressing expertly done. In the opening scenes of the film, it’s unclear in which decade the story actually takes place: At home or in one of her private clubs, Florence appears to live in the early part of the 20th century. It’s only when we get out into the street that we realize the war with Germany discussed in the pervious scene was World War II, not World War I, and this is 1944, not 1918. It’s a subtle but effective technique that conveys the vast gulf between Florence and Bayfield’s “happy little world” and the real world around them. If Frears and screenwriter Nicholas Martin had retreated further inward still, to explore how and why Florence got to the point where her whole life became an elaborate white lie, this could have been a great film. Instead, it’s just a feel-good one.