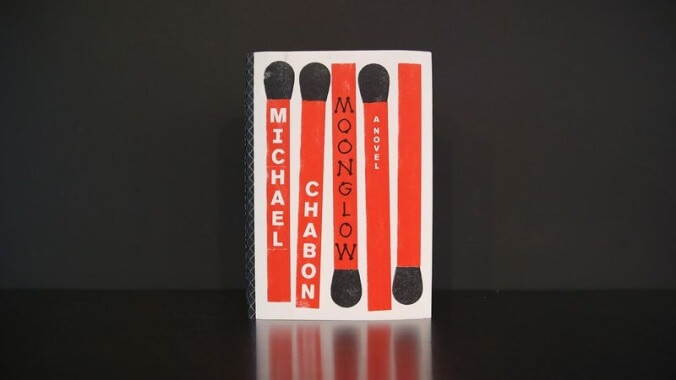

Michael Chabon reins it in with the intimate Moonglow

Opening with a quote from Wernher Von Braun, followed quickly by the image of a rocket—a photocopied advertisement, rather than one screaming across the sky—Michael Chabon’s latest, Moonglow, begins with an invocation of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. But whereas Pynchon goes sprawling, Chabon gets intimate, narrowing his scope considerably from his previous novels. In fact, Moonglow—though its themes of Jewish identity, paternity, and contemporary masculinity reflect Chabon’s career-long concerns—represents a distinct break with his previous efforts. Since his debut, The Mysteries Of Pittsburgh, Chabon’s work has continued to grow bigger, in length, scope, and style (the latter reaching its apotheosis in Telegraph Avenue’s 11-page long sentence). Moonglow, however, represents a noticeable change. It reads as the kind of axial work on which lengthy, rich careers rotate.

The novel serves as a fictional memoir that encompasses the lives of Chabon’s grandfather as well as the author himself. “In preparing this memoir,” Chabon writes in an author’s note, “I have stuck to facts except when facts refused to conform with memory, narrative purpose, or the truth as I prefer to understand it.” Conceived as a conversation between Chabon and his grandfather, the work is noticeably smaller in scale than his preceding efforts. The scenes are intimate and brief, illuminated by their details: Chabon rendering his grandfather’s tics as he requests more juice; a footnote adding Chabon’s mother’s response to reading the manuscript. Here Moonglow finds both its saving grace and its greatest detriment. Formally, the novel evinces a mature artist willing to engage with the complexities afforded to the novel as a medium, and though its story may be simple and straightforward, the telling is anything but. Moving fluidly backward and forward in time, the novel’s conceit allows Chabon to assume a multiplicity of perspectives, from first-person to an approximated third-person. This technique allows Chabon to recall his fictive grandfather’s life with impossible detail, obscuring his own unreliability with a modulated first-person perspective. And yet, Chabon’s first-person precludes him from revealing the psychological interiority of his characters. The memoir construction makes this paradoxical storytelling seem sensible. It works perfectly and is barely noticeable—the mark of expertly employed aesthetic tools.

Moonglow feels refined, polished, and sharpened to a fine point. Its flat-footed sentences are crisp and clear: “On the way home from the crab house, he obliged himself to drive patiently. The effort required kept his mind off the pain.” There is an elegance and simplicity, and the dominance of such a direct style makes something like the following stand out more: “The smirk and swagger that had unaccountably chosen this man as the vehicle for their conquest of the world or at least the Delmarva Peninsula had reached some kind of new pinnacle of insufferability.”

And yet, Chabon compartmentalizes his scenes—not that they seem modular, but rather, they seem to be seen through a narrow lens—and in its perfectly coiffed refinement, Chabon has hermetically sealed Moonglow. That isn’t to say the novel is bad—quite the opposite. Chabon marries the imminent and pleasurable readability of his Wonder Boys with a new formal maturity that lacks the cloying paeans to nerd culture that sometimes mar his Telegraph Avenue. The result is moving, dreamy, and deeply lucid, a book whose pages fall away as quickly as the eye can scan them. For example, Chabon uses a skinless horse as a motif, a recurring image of depression and despair seen by his mother and grandmother, and the specter haunts Moonglow. And yet, there is an absence as well. Whereas The Amazing Adventures Of Kavalier & Clay or The Yiddish Policemen’s Union are warm, desperate, intuitive, and fumbling, Moonglow is more technical. Overly groomed, it feels sanitized—almost obsessively so. There are no missteps, nothing askew, nothing out of place. It’s too safe. And while that makes for an enjoyable—even compelling—read, it delimits the book’s effectiveness. It cannot penetrate its readers in the same way a less composed but more ambitious novel may. It plunges its hand into the reader’s heart, but it moves too slowly, digs too shallowly. Chabon has produced an excellent novel but not a great one.

Purchasing Moonglow via Amazon helps support The A.V. Club.