Michael J. Fox poignantly reflects on mortality and his famous optimism in No Time Like The Future

With his latest memoir, No Time Like The Future: An Optimist Considers Mortality, Michael J. Fox reminds us that hope is an exercise and a discipline, not just a feeling or even a state of mind. The actor, author, and activist has already published three books, including two earlier memoirs, that course with the optimism he’s maintained nearly 30 years since being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Introspective and poignant, No Time Like The Future is the latest installment in Fox’s series of reflections on just how hard-won that famous sense of hope is.

Fox and his longtime producing partner, Nelle Fortenberry, who helped the Back To The Future and Spin City star get these words on paper, say they approached this latest memoir as a film or TV series. Though it skips around a bit, the story is mostly linear, carried by an easy, almost upbeat rhythm. First, a challenge presents itself, then Fox and his extended support network—including Nelle, his family, and assistant-turned-manager Nina—work together to overcome it. Fox’s belief in a positive outcome, or just making it through the current setback, rarely ever wavers. But his optimism isn’t of the borderline fatalistic variety, of keeping your fingers crossed that things will work out some way, somehow. The grim reality is that Fox and his family have been through these things before: injuries, hospitalizations, physical therapy. The author’s resolve has been burnished by adversity, something he shares with his loved ones. If his hope is unfaltering, it’s because the love and support from his family and friends is steadfast.

But, just as in any Hollywood story, a new conflict emerges at the end of the second act, one that’s hinted at in the ominous opening. In the summer of 2018, just months after completing physical therapy following the removal of a benign spinal tumor, Fox takes a fall in his Manhattan home. The tumble shatters his left arm, necessitating his second surgery in the span of a year. Mending Fox’s arm requires a stainless steel plate and 19 screws, but his doctors are even more concerned about how this latest injury will affect his recovery from the tumor excision. At the beginning of 2018, the actor essentially had to learn to walk again in physical therapy; that August, Fox had to worry about how having an arm in a sling would affect his already compromised gait and balance.

Fox’s wry humor remains intact even when recounting this low point, but something’s shifted. For the first time, his confidence is in short supply: “[I]f optimism is my faith, I fear I’m losing my religion.” Just as prominent as the pain shooting up his left arm is a sense of shame. The author is mortified that he’ll have to “do it all over again”—undergoing physical rehab, hiring round-the-clock aides, having his every move monitored. More than the prospect of another round of recovery, Fox contends with the fear that, since his Parkinson’s diagnosis, he’s “progressed into something dangerous. I’ve been weaponized. Most recently, my mobility and balance issues have definitely worsened.” For people with Parkinson’s, “progress” is almost an oxymoron—as Fox writes, “getting better isn’t part of the vernacular.” The terms “progressing” and “advancing” can take on an almost sinister meaning, because, as the author notes, while no one with Parkinson’s dies from it, they all die with it.

Despite the aforementioned production-style approach to the book, this darkest-before-dawn moment is less a narrative device than it is an epiphany. Fox is ready to acknowledge the tolls that time and Parkinson’s have exacted on him. He’s never lugubrious, even as doubts crowd out memories of happier times. Fox’s pluck still shines through, especially in the asides scattered throughout even the most troubling passages. His gratitude is also ever-present as he recounts the second act of his career, including an Emmy-nominated stint on Rescue Me and an Emmy-winning turn on The Good Fight. But there’s no denying that there’s something different about this latest phase in his life. Before meeting it head-on, Fox shows greater vulnerability than ever before by just sitting with it, and with the possibility that, despite his best efforts, things might not work out.

Fox’s earlier memoirs, Lucky Man: A Memoir and Always Looking Up: The Adventures Of An Incurable Optimist, also centered on how Parkinson’s had changed his life. For a while, No Time Like The Future departs from those books by contemplating mortality, but it still feels part of a series. In Lucky Man, Fox expressed his gratitude for everything he accomplished before being diagnosed, and everything he’d accomplished since. Always Looking Up, published in 2009, saw him double down on his gratefulness and optimism. No Time Like The Future reflects both the culmination of his own philosophy and the greatest test of it. In the epilogue, Fox quotes his late father-in-law, Stephen Pollan: “With gratitude, optimism becomes sustainable.” No Time Like The Future sees Fox drained of his optimism only to find a new source for it.

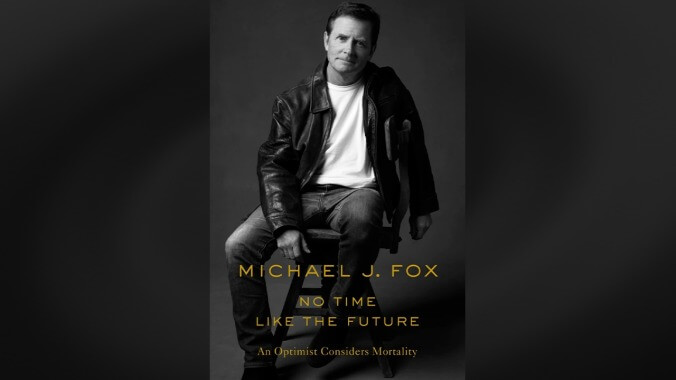

Author photo: Mark Seligerf