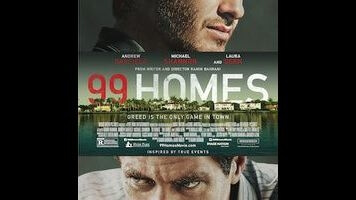

Michael Shannon is greed incarnate in Ramin Bahrani’s overwrought 99 Homes

Ramin Bahrani makes films about the little guys. Even as his budgets have expanded and his industry clout has increased, the indie director has continued to shine a light on marginalized Americans, the people living and working on the fringes of our culture. What’s changed is not the what of his films, but the how: Where once he operated in a kind of neorealist mode, sketching vividly observational portraits of economic struggle like Man Push Cart and Chop Shop, Bahrani now folds his social concerns into slicker, more star-studded packages. 99 Homes, a kind of Wall Street for the Florida real-estate market, is easily the loudest, plottiest, and most conventionally dramatic movie he’s made yet. And while its righteous rage is bracing, fans of the filmmaker Bahrani used to be will mourn the subtlety and careful character development of his early triumphs. His heart remains in the right place, but his head has gone hopelessly Hollywood.

Set in 2010, after the bubble burst on Orlando’s housing boom, 99 Homes casts a suitably frazzled Andrew Garfield as Dennis Nash, an unemployed construction worker and down-on-his-luck single father. Three months behind on his mortgage, Nash is unceremoniously ejected from his family home, and forced to move his son (Noah Lomax) and mother (Laura Dern) into a tiny, fleabag motel, where other fellow evictees have indefinitely relocated. Bitterly ironic salvation comes in the form of Rick Carver (Michael Shannon), the ruthless realtor who oversaw the seizure of Nash’s beloved home and flipped it for a quick profit. Carver, who’s turned repossession into big business, is hiring, and Nash is in no position to turn down the work. Before long, our hero is the one issuing eviction notices; fully under the wing of his real-estate-mogul boss, Nash learns the crooked trade, selling out his neighbors for a shot at getting his house back—and maybe, also, for a taste of the 1 percent luxury Carver lets him sample.

Desperation looks good on Garfield, who coils with volatility during the big eviction scene—a gut-wrenching spectacle of bureaucratic indecency—and makes his subsequent turn to the cash-for-keys dark side mostly believable. But 99 Homes has little room for emotional nuance. It’s a heavy-handed morality play with the thunderous pulse of an action thriller, and Bahrani, going bigger and broader than usual, directs it with maximum sound and fury—all shouting matches, urgent montages, and scenes of Shannon’s cartoon fat cat extoling the virtues of greed. As a result, the film’s central mentor-protégé relationship never deepens into anything more complicated than a Faustian pact.

Part of the problem is the villain, who Bahrani and his co-writers, Amir Naderi and Bahareh Azimi, introduce casually shrugging off the bloody suicide of one of the men he’s rendered homeless. No doubt there are plenty of real-life scoundrels just like Carver, a callous housing baron who’s learned how to prey on the misfortune of the downtrodden and twist a broken system to his advantage. But the film conceives of him as a kind of pragmatic Mephistopheles, pure evil in a white collar. And Shannon, sucking menacingly on an electronic cigarette when not delivering supervillain monologues, plays the character exactly as he’s written—which is to say, with scarcely a trace of humanity. His General Zod looks like Kal-El by comparison.

99 Homes wants to get the blood boiling, a task it accomplishes most effectively when simply depicting the hardships of foreclosure: Scenes of honest Americans booted off their properties, their possessions arranged in stacks on the front lawn, are powerfully upsetting, as are the glimpses of Florida rocket docket proceedings, wherein the suddenly destitute have a mere minute to argue their case in court. Why Bahrani felt the need to Trojan horse this subject matter to audiences in the form of a mainstream melodrama—complete with an armed showdown, sad-eyed moppet onlookers, and a bad guy that’s basically an effigy waiting to be burned—is anyone’s guess. All the edge-of-your-seat bombast just dilutes the power of the filmmaker’s well-researched, well-meaning lament for struggling homeowners. The smaller his movies get, the bigger his compassion looks.