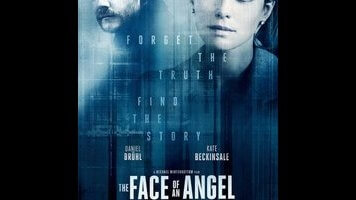

“If you’re going to make a film, make it a fiction,” someone advises director Thomas (Daniel Brühl) toward the beginning of Michael Winterbottom’s The Face Of An Angel. That directive doesn’t always come easily to Winterbottom himself, the workhorse English filmmaker whose filmography zigzags back and forth along the line separating cinema from real life, from the docudrama of A Mighty Heart to the unsimulated sex of 9 Songs to the self-referentiality of his comedies starring Steve Coogan as himself (Tristram Shandy: A Cock And Bull Story and the Trip series). It’s not surprising, then, that Winterbottom does not offer a straight examination of Amanda Knox, the American student accused, convicted, acquitted, re-convicted, and eventually exonerated of the murder of housemate Meredith Kercher. Though the movie is based on a 2010 book about the case by a Daily Beast reporter, Winterbottom fictionalizes it into a series of thin veils: Amanda Knox (dubbed “Foxy Knoxy” by the tabloids) becomes Jessica Fuller (with the slightly more obtuse press nickname “Jessica Rabbit”), reporter Barbie Latza Nadeau becomes Simone Ford (Kate Beckinsale), and her book Angel Face becomes The Face Of An Angel.

It’s hard to say whether, during the pre-production or making of the movie, Winterbottom became Brühl’s Thomas (or vice versa), a filmmaker researching the fictionalized case for a possible comeback project. It seems unlikely if only because Winterbottom has often come across as an inquisitive, genre-hopping, productive director in the vein of Steven Soderbergh, rather than the blocked, flailing dope presented here. If the character does represent self-criticism, though, give Winterbottom points for refusing to make himself look good, or even particularly talented. (Intentionally or not, Thomas’ abortive attempts to write a screenplay, occasionally glimpsed on-screen, read more like a loose outline with a few scene headings sprinkled in.)

The movie starts out from an intriguing pack-journalism vantage point. Thomas is also advised that his fiction feature could capture “that whole world of foreign correspondents,” and when reporters swarm to capture Jessica Fuller or other trial participants, Winterbottom often places the camera in the middle or back of the scrum, emphasizing the crowd around the proceedings over the proceedings themselves. Eventually, though, Thomas and the movie drift away from these ideas in favor of the filmmaker’s stumbling attempts to absorb details about the Italian city of Siena, with a friendly early-20s student (Cara Delevingne) as his mildly flirtatious guide. In between ventures into the night, Thomas develops a hot-and-cold relationship with Simone and briefly gets entangled, Zodiac-style, in some secondhand details of the case; he also goes on about filtering his film through Dante’s The Divine Comedy. Some of this material is interesting, before it starts to blur into a circle of repetitive elements: lines of cocaine, walks down dark alleys, fake-out dream sequences, and the endless cheek-kissing greetings that seem to constitute about a third of the movie’s 100 minutes.

The many dead ends are probably supposed to make an incisive point about Thomas losing himself as he tries to comprehend the case, but mere self-awareness isn’t a cure for the movie’s chronic solipsism. The focus on one man’s career crisis just wastes the charismatic performances of Brühl, Beckinsale, and Delevingne, not to mention its fascinating subject matter. Early on, Jessica Fuller is described as “like a film star” in her unseemly celebrity, but the movie barely bothers projecting anything on her. It purports to be more interested in poor overlooked Elizabeth Pryce (which is to say Meredith Kercher, who receives the movie’s dedication), and tries to locate a spiritual mournfulness in her untimely death, lost in the tabloid noise. Unfortunately, the movie does this mostly through shots of her face, which don’t really suffice, emotionally speaking. Eventually, Winterbottom lurches into an ending better suited for a more thoughtful film, one that more directly addresses the widespread fascination with Knox’s case. Past Winterbottom films have turned “real life” into both comedy and tragedy. The Face Of An Angel turns it into a directionless skulk.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.