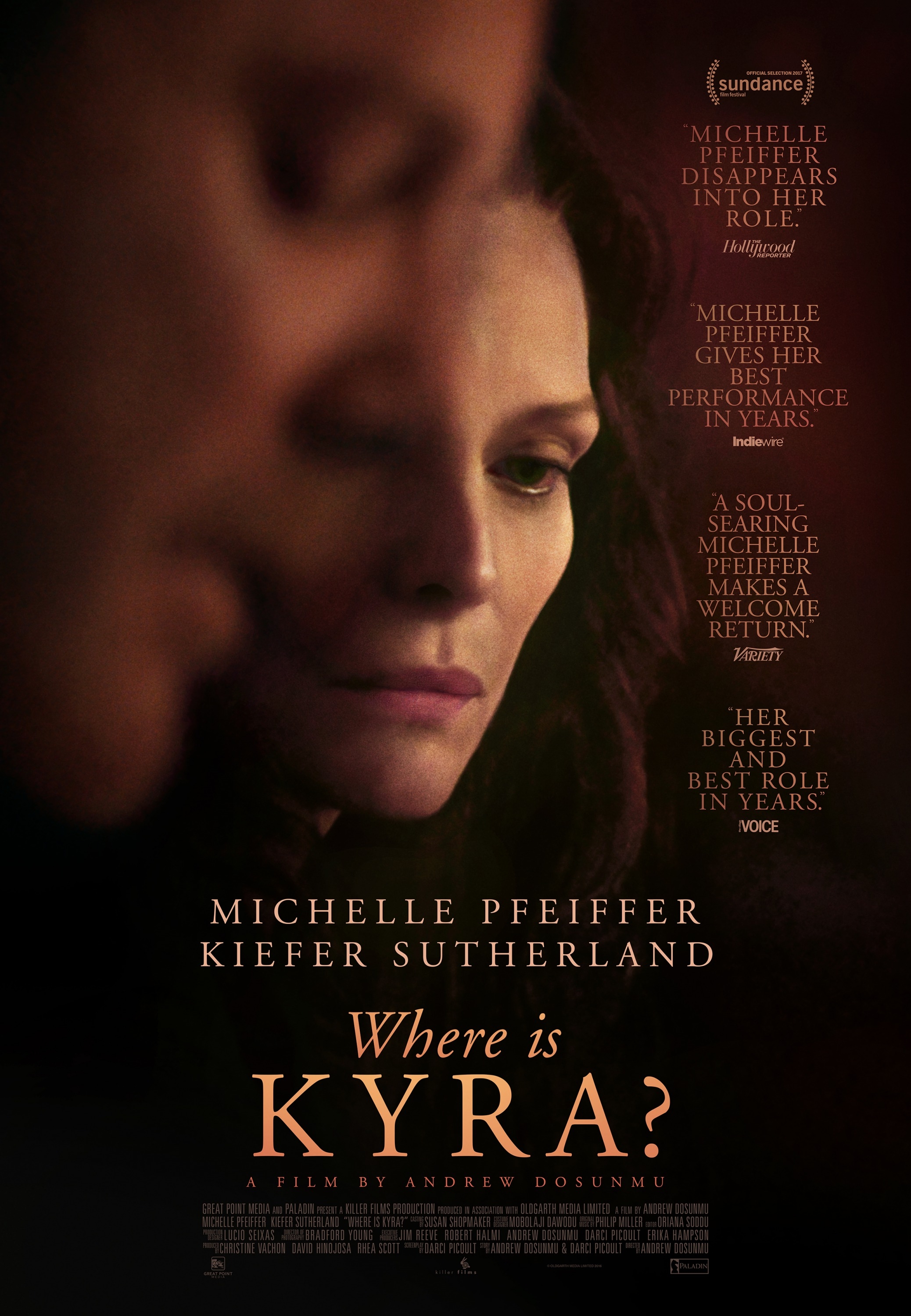

Michelle Pfeiffer disappears into literal and figurative darkness in the bold Where Is Kyra?

Now and then, a movie attempts something so unorthodox that certain theaters notify customers in advance that what they’ll experience is not a projection error. Signs outside multiplexes showing Crooklyn (1994), for example, warned patrons about one lengthy sequence that Spike Lee shot anamorphically and then chose not to unsqueeze, creating deliberately distorted images that really did look as if they must be a mistake. More recently, Rian Johnson’s decision to cut all sound for a key moment in The Last Jedi inspired at least two AMC theaters to put up a similar notice (though they were quickly taken down after being shared on social media), explaining, “This is intentionally done by the director for a creative effect.”

The same thing could potentially occur with the new indie drama Where Is Kyra?, especially if it plays in some of the many U.S. theaters that show movies at less than the industry-standard 14 foot-lamberts. Lit by the superb cinematographer Bradford Young (Arrival, Selma, Ain’t Them Bodies Saints), this is the darkest film—emotionally, sure, but also in terms of literally just being able to see what’s going on through the gloom—since perhaps the climax of Unforgiven. “That should have been called Where Is The Damn Light Switch?” multiple jokers will surely crack. It’s a bold, initially alienating choice on the part of Young and director Andrew Dosunmu (who previously collaborated on Mother Of George), and they push that morose aesthetic even further via compositions that keep characters at a distance, or isolate them in tiny slivers of the frame, or keep them out of the frame entirely as they’re speaking. Over time, their approach takes on an elemental power that justifies its extremity. It’s the correct look for a singularly grim vision.

The film’s screenplay, written (like Mother Of George) by Dosunmu and Darci Picoult, isn’t much more forthcoming. Kyra (Michelle Pfeiffer) is first seen tending to her elderly mother, Ruth (Suzanne Shepherd), who’s so frail that she can barely walk without assistance. Ruth soon dies, and it gradually becomes clear, in a fragmented and discursive way, that Kyra was downsized two years earlier and depended on Mom’s pension checks to survive. We see her apply for one dead-end, minimum-wage job after another, getting stiffly polite responses from employers who pretty clearly aren’t looking for someone who’s pushing 60. A tentative romance with an almost equally broke neighbor, Doug (Kiefer Sutherland), lifts her spirits a bit, but neither he nor her ex-husband (Sam Robards) can offer any financial help. So dire do Kyra’s straits become that she repeatedly dresses up as her dead mother and fake-hobbles her way to the bank, cashing checks that are still arriving in the mail due to a clerical error. That’s a criminal act, of course, constituting fraud, but the sheer desperation and attendant loss of dignity that drive it are what register most strongly.

Unlike Oren Moverman’s superficially similar Time Out Of Mind, in which Richard Gere plays a homeless man, Where Is Kyra? doesn’t constantly feel like what it necessarily is: the work of wealthy people simulating poverty. In part, that’s thanks to Pfeiffer’s vanity-free, internalized performance, which could hardly be more different from her deliciously abrasive turn in last year’s Mother! (It’s great to have her back.) Dosunmu and Young give her one extended close-up, when she swallows her pride and begs her ex for a loan (in front of his pregnant new wife), but they otherwise keep her so distant and/or shrouded that pleading for audience sympathy would be impossible even were she inclined to do so, which she decidedly isn’t. One needs to be in the right mood for an experience like this—Kyra is relentlessly bleak, building to a final scene that’s almost painful to endure, and it ultimately doesn’t have much to say apart from the basic observation that life is very, very hard for people with zero resources. But it depicts that punishing world with singular artistry. There’s a reason why this woman is so hard to see.