Mickey tells the tales of pathetic struggles in a most relatable way

Mickey opens with a Matchbox Twenty lyric, from the song “3 AM.” If you know anything about that band’s debut album, which came out 20 years ago, you know that the song’s lyrics “It’s all gonna end and it might as well be my fault” aren’t actually about a breakup. They’re about lead singer Rob Thomas’ mother, who died of cancer. In a similar vein, Mickey ends up being a lot less about the protagonist’s breakup with Mickey and more about the universal feelings of frustration and loneliness that come with growing older while not necessarily maturing.

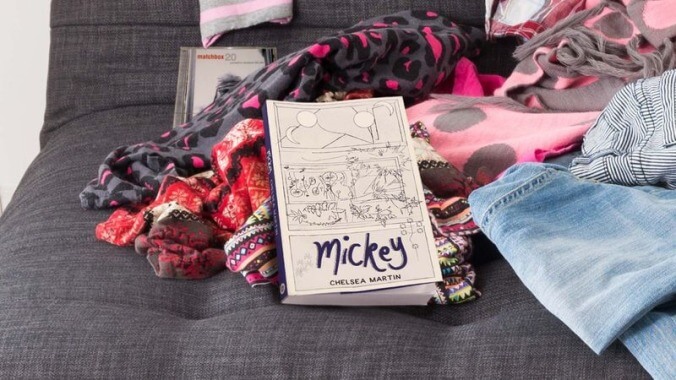

Presented with brevity through a series of short vignettes, author and illustrator Chelsea Martin’s fourth book finds the humor in minor tragedies. Like when Martin writes of the protagonist’s break up: “I value breaking up with someone because of the time it affords me to contemplate all the bad decisions I’ve made and exploit them for creative content.” It’s a silver lining of sorts, and it’s delivered completely deadpan, endearing the reader to the author’s way of defending her character with selfishness—a trait that otherwise might annoy, if not for the circumstances surrounding the young woman. And it’s not just the lingering breakup: There’s tension between both her and her roommate, Jessica, and the her and her mother.

Jessica is also an artist, but her determination is more pronounced, propelling her career faster and keeping her in enough cash to make her rent. Meanwhile, the oscillating depression and anxiety eventually land the main character on the couch, after losing her job, while a friend pays rent and takes over her room. But again, Martin turns these misfortunes into literary worth with musings:

“Don’t Hot Cheetos give you heartburn?” I asked the abyss.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.